Louisa Francis Bihinang, Mariana Vilana, Antonio Estudillo, Suyon and Maura.

These are a few of the Filipinos and Indigenous people who died after they were brought to the U.S. for the 1904 World’s Fair as part of the largest “human zoos” of the time.

And Janna Langholz wants to make sure their names aren’t lost to history.

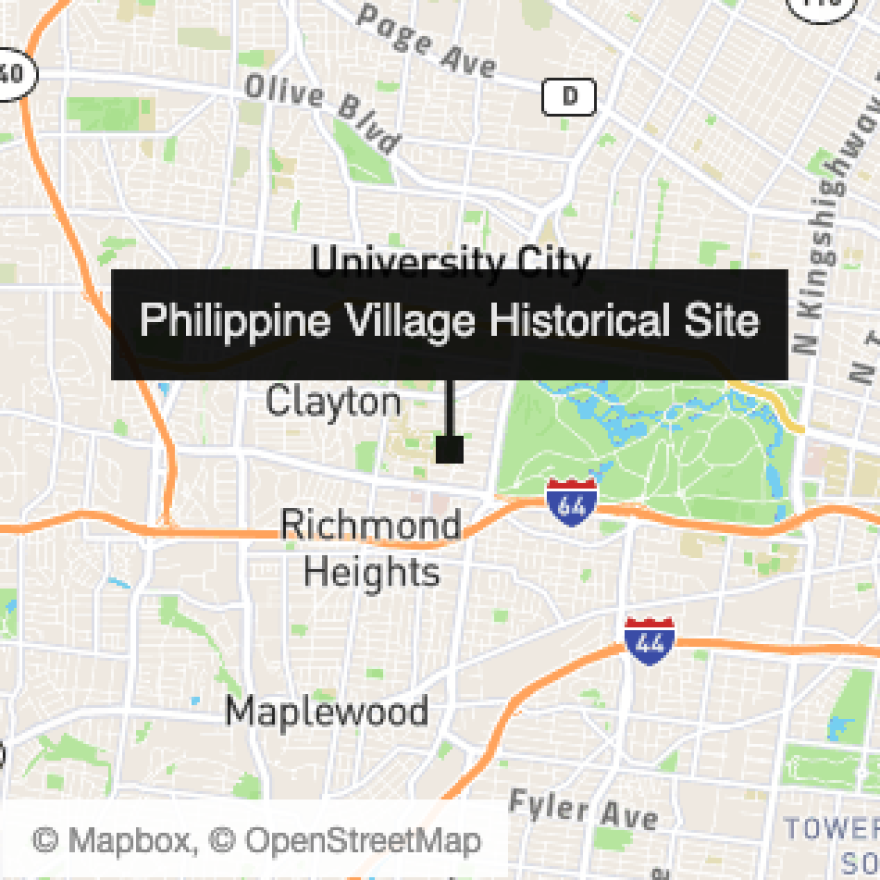

She’s an interdisciplinary artist who lives and conducts her research at the Philippine Village Historical Site, a 40-acre stretch of land in Clayton that was once part of the World’s Fair.

As the site’s caretaker, Langholz traces each individual’s life story as a way to humanize and remember them, but also to counter an image of the World’s Fair that lingers today.

“A lot of people here still celebrate that history or simply aren't aware of it, when I see it as being one of the most racist and tragic events in American history, especially for Filipinos and people of color,” said Langholz, who is Filipino American.

Nearly 1,200 Filipino and Indigenous people from the archipelago arrived in St. Louis in April 1904, along with Mbuti tribe members from central Africa and the Ainu people from Japan. Angela da Silva, a local history expert, said the groups on display were arranged in a hierarchy, from most “primitive” to “advanced.”

“All this did was reinforce the cultural distance, if you will, between what they consider the primitives and white society,” da Silva said. She added that visitors would throw rocks, garbage and even urine at the people inside the enclosures.

The human displays reinforced racist and inaccurate stereotypes about Indigenous people. Infamously, when fair officials learned that the Igorot people from northern Luzon consumed dogs during certain religious ceremonies, they were forced to eat up to 20 dogs per week in front of fairgoers.

Comparing Indigenous people to more “civilized” groups also provided justification for military and commercial efforts the United States had made in recent years, said Terese Monberg, an associate professor at Michigan State University.

“It gave the American people something to understand about why we were there, why the U.S. was in the Philippines, and to justify our territorial colonization of the Philippines,” she said.

A personal connection

Langholz said she delved into historical research about the 1904 World’s Fair while in graduate school, beginning in 2013.

“I was born at the site of the World's Fair and have been a St. Louis resident my whole life,” she said. “So I think that history has always been intertwined with the environment that I grew up in and continue to live in today.”

Her personal connection to the work propelled Langholz to keep scouring old newspaper clippings from 1903 and 1904 to corroborate historical records of Filipino individuals who died shortly after arriving in St. Louis, nearly all of disease.

One person she discovered was named Maura, an 18-year-old Igorot woman from Suyoc, who died of pneumonia on April 15, 1904.

Langholz was struck by Maura’s story, learning that she and other Indigenous people from the Philippines traveled from Seattle to St. Louis in a packed train car without heat.

“Being in the north, Baguio and the Cordilleras is the coldest part of the Philippines, but ‘cold’ means people start putting on sweaters and coats when it's in the 50s outside,” Langholz said.

She pointed out that the spring of 1904 was unseasonably chilly even by Missouri standards, with snowfall in April. “To have suffered over 48 hours in a locked train without the proper clothing or preparation in the freezing cold is cruel, inhumane, just absolutely unthinkable to imagine how horrible it must have been.”

According to Jose D. Fermin’s 1904 World’s Fair: the Filipino Experience, officials anticipated the loss of life and prepared gravesites in two St. Louis cemeteries specifically for the Filipino and Indigenous people before their arrival in the city. Tribes were prevented from carrying out funeral traditions in favor of having a Christian burial.

Part of Langholz’s research is to find Maura’s and other unmarked gravesites in St. Louis cemeteries — a time-consuming and emotional process of digging through archives to match vague descriptions with individual’s names in newspaper articles published at the time.

An incomplete history

Such tragedies are often overlooked in modern-day American retellings of the 1904 World’s Fair, more known for touting technological advances such as the X-ray machine, baby incubators and personal automobiles. The legacy of the fairgrounds as a place of splendor and grandeur with towering “palaces” solidified through pop culture like the 1944 movie-musical "Meet Me in St. Louis," which starred Judy Garland.

Historical omissions make work by Filipino historians and scholars like Langholz even more vital for several reasons, said Monberg, who is also a board member of the National Filipino American Historical Society. She said that the dominant narrative of progress at the World’s Fair, and silence about those who were exploited, can perpetuate harmful stereotypes today.

“The ability to sort of center the stories of Asian Americans or Filipinos is essential, for several reasons, because the history has been largely documented by others,” Monberg said, adding that Filipino American, or Asian American, history is rarely taught in K-12 schools.

Scholar Angela da Silva said the need for reconciliatory remembrance of history is crucial for healing racial divides which persist today. In 2018, Da Silva directed a historical reenactment of how people of color were treated at the World’s Fair with the Mary Meachum society.

She said audiences were shocked, and some people even were defensive of the fair’s legacy.

“If St. Louis was not ashamed of it, why have they buried this and kept it buried for so long?” da Silva said. “But why? I mean, if this was OK, and you're so proud of this event, then why not tell the whole story?”

Da Silva said instead of justifying the event for being “acceptable at the time,” people in the present day should engage with history recognizing the wrongdoing that occurred. In her words, “both sides should face the truth.”

It’s something many historians are grappling with. Adam Kloppe, public historian for the Missouri Historical Society, said there has been an increased effort in the past 30 years to try to recenter marginalized perspectives from the fair’s legacy.

“Looking at history and all of its complexity can give us a much fuller picture of what the past was and what it was like, how we can take lessons from the past, and apply them to the present to make our world a little bit better for everybody,” he said.

He added that the Missouri Historical Museum’s permanent exhibit on the World’s Fair will be updated next year with a more diverse approach.

Seeking peace

Langholz runs and operates the Philippine Village Historical Site out of her apartment, where she hopes to run a community and event space for Filipino Americans someday. She said it’s been a challenge to make due with limited resources, but she is hopeful about making more tangible changes to the neighborhood, such as a memorial tree with the names of individuals who died.

When she first began her work, Langholz focused her efforts on community building by launching the Filipino American Artist Directory. It brought together 1,200 artists who gathered at the Philippine Village Historical Site to pay homage to the same number of Filipinos who were brought to St. Louis.

Since the pandemic started, Langholz switched gears to promote historical preservation efforts instead. She said she made a sign for the historical site just a few weeks ago and plans to give walking tours and host events in the near future.

“I didn’t realize how much of an impact having a sign would make, but I think the fact that it’s here gives people hope, that something is being done to address this collective trauma that has been buried in history for 117 years,” she said.

Already, she has received messages from St. Louisans saying her Instagram account was the first time they’ve ever heard about this aspect of the World’s Fair. Eventually, she hopes to add a memorial tree with the names of the individuals who died.

“I want peace for those who died here, and once that is achieved I feel that I can have peace myself too,” she said.

Follow Megan on Twitter: @meganisonline

Maps are © Mapbox © OpenStreetMap Improve the map