This article first appeared in the St. Louis Beacon, July 5, 2013: I knew before I arrived in Barcelona that I would find Bob Cassilly there.

Antoni Gaudi’s tile-bejeweled lizard and cement serpents in Park Güell (pronounced: Well) are close relatives to the sculptures Cassilly inserted in spaces all over the St. Louis City Museum. Mosaics made from broken tile shards cover walls, floor, ceilings and sculptures in much of the architecture designed by Gaudi (1852-1926). The decorative mosaic technique is called trencadis when employed in the method made famous by Gaudi.

Gaudi (1852-1926) is referred to as the father of Catalan modernism. His architectural oeuvre is associated with Art Nouveau, but he is not considered to have been the center of a clearly defined art movement. Yet, Bob Cassilly’s City Museum and his many other sculptures found in St. Louis, New York and elsewhere are quite clearly part of a larger group.

Austria’s famous Friedensreich Hundertwasser (1928-2000) built numerous buildings in Vienna and around the world that follow a similar aesthetic. Sao Paulo, Brazil has Estevao Conceicao, who only learned of Gaudi after he had been told that his life-long building project had a storied antecedent. Jeff Lockheed’s Venice Café in St. Louis’s Benton Park and Bill Christman’s Ars Populi and Joe’s Café are also part of this aesthetic family. In each case, the artist/architect is often described as creating a “distinctly unique style.”

Gaudi wrote extensively (as did Hundertwasser) about his quest to duplicate in sculpture and architecture the ideal forms he found in nature. The extraordinary shapes that his buildings took are remarkably similar to those found in Cassilly’s art. Parabolic arches and organic curved lines mark this global style. It is a style that incurs a universal response. People everywhere love these spaces in which the basic expectations of floor, stairwell, walls… are met with completely unexpected materials and forms.

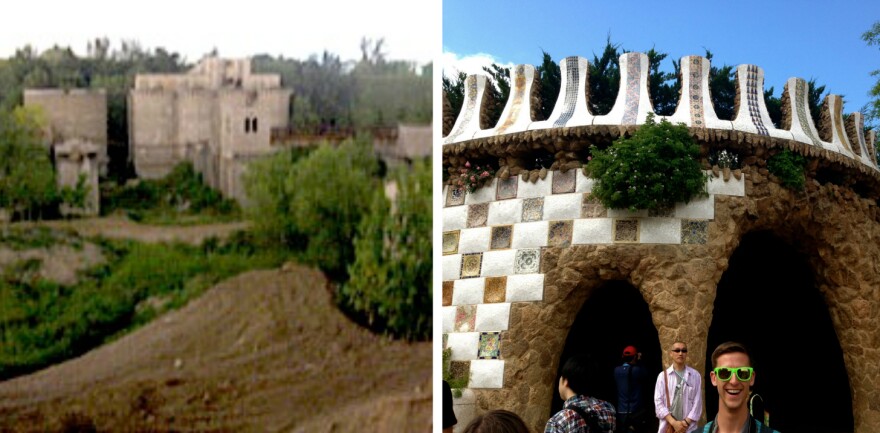

I knew before I arrived in Barcelona that I would find Bob Cassilly there. But I did not consider the implication of finding Gaudi’s great unfinished cathedral, Sagrada Familia. Like Cassily’s Cementland, this was Gaudi’s final project, a project he had barely begun when struck by a tram and killed at age 74. Sagrada Familia is still under development. It grows increasingly amazing, all due to local investment and the enthusiastic public support of tourists who flock to the site in their pilgrimage to see everything dreamt into being by Gaudi.

When compared to the 2000 years of Barcelona’s history, St. Louis is just beginning. Yet, St. Louis, in this developmental stage, manages to draw in tourists who come to see the sometimes struggling city’s diverse creative capital. The two are intrinsically linked – the inspired, fantastical vision of artists and those who will come to live, work and play in a place that is both unique and universal. Put like this, the future of Cementland can be seen as a test. Will St. Louis prove worthy and able of fulfilling this vision? As shown by the slow progress that is ongoing at Sagrada Familia, the commitment need only be made, the completion date is less important.