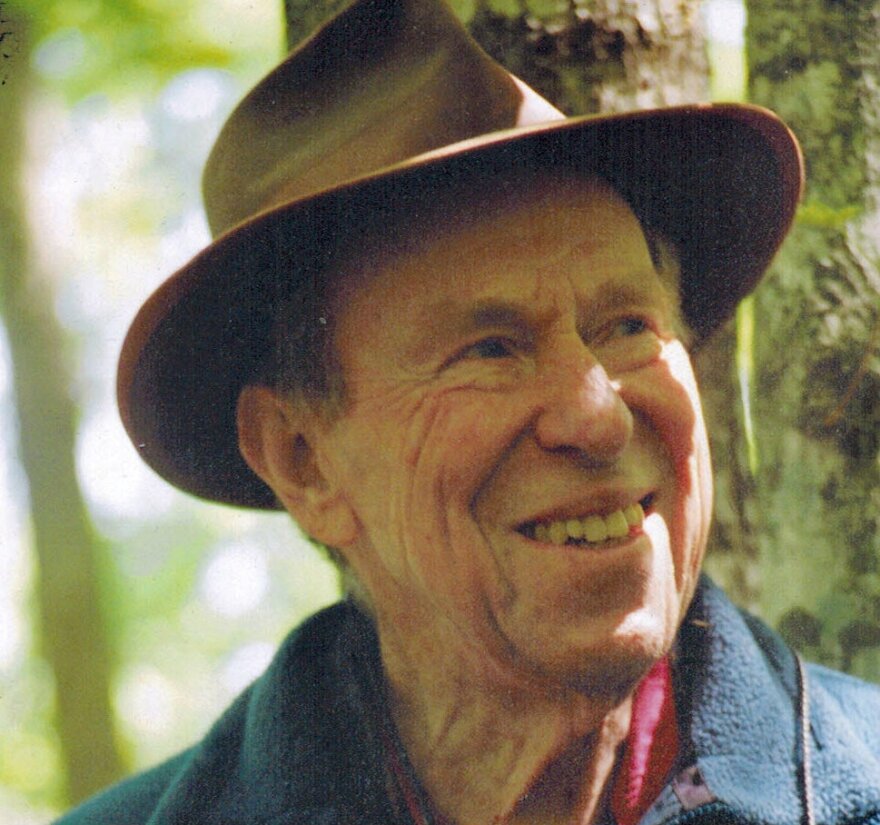

In 1929, Luther Ely Smith, whom the National Park Service calls “the father of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial,” convened a group of civic worthies for lunch at the old Noonday Club downtown. Later on, a fellow named Leo Drey joined the group. Mr. Drey, who died Wednesday at the age of 98, would become a stalwart member of the group, and one of its most dynamic leaders.

Out of that convocation came enormous positive activity for the public weal. Florence Shinkle, a former writer for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and an ardent conservationist, was invited to come along at some point to join in the Wednesday discussions. She recalled that plans were laid at the table for saving Greer Spring, for saving open space all over the state. In general, the participants plotted successfully to advance many, many other causes regarded by them as worthy – and for ambushing plans they regarded as antithetical to the public good.

The group was made up of political liberals, always rarae aves in professional and commercial St. Louis ranks. All were involved one way or another with fair housing, or with fighting the erosion or destruction of parkland by natural, commercial or governmental forces, or with lobbying for the protection of environmental resources, and they pressed for the maintenance of free-flowing streams and springs, forests, trees and wilderness -- or all of those things.

Three members provided exceptional leadership in Shinkle’s days at table, she said. One was Joseph P. Logan, a partner in the Thompson Coburn law firm. Another was the late Lewis C. Green, the famous, indefatigable St. Louis environmental attorney. The third was businessman Leo A. Drey. “When the three of them gave the orders, we saluted, cheered and went to work,” Shinkle said.

Mr. Drey died at home in University City on Tuesday.

Leo Albert Drey was born in St. Louis in 1917. He graduated from John Burroughs School and from Antioch College, Yellow Springs, Ohio. He began a career in business, but soon was drafted and served as an officer in the U.S. Army during World War II. After his service, Mr. Drey returned to St. Louis and joined the old Wohl Shoe Co. in St. Louis as assistant to its treasurer.

“It is difficult to accept the fact that he is gone,” said Joseph Logan of the Wednesday luncheon group. “Leo was distinguished in a number of ways, but two stand out. One in particular was in regard to forest management,” Logan said. Mr. Drey’s approach was single-tree selection harvesting, which avoids clear cutting and embraces a model that produces uneven or all-aged growth. The other main distinction, Logan said, was his character -- his generosity, which is legendary, along with his honesty, his good manners and kindness.

John Karel was something of a protégé of Mr. Drey, having met him when he was in graduate school studying natural resources at the University of Missouri. Karel, retired director of Tower Grove Park, is now president of the board of directors of the L-A-D Foundation, a conservation-centered foundation created by Mr. Drey in 1962.

Karel said Mr. Drey’s forest management system is his legacy. It is a system, he said, that not only sustains the forests, but is productive in terms of yielding timber. Karel said that Mr. Drey’s harvesting philosophy also helps to maintain the work force of the forested area, maintains the integrity of the land and the quality and health of the watershed and provides recreational opportunities.

As did Logan, Karel remarked on Mr. Drey’s soft-spoken, self-effacing qualities, his ability to put everyone at his or her ease, despite the fact that when Karel met him he was “already a legend, whose name was brought up frequently as a model citizen.”

Karel noted also the fact that Mr. Drey chose to do this work in Missouri. “He chose not to try to save the whole world himself, but focused his attention on Missouri, and helped to establish a much better quality of life. He had a wide ranging influence, but made Missouri his focus,” Karel said, “and made a long-range impact on all of us who live in this state." (Listen to an NPR report on Mr. Drey's management.)

Mr. Drey’s son, Leonard Drey, wrote an appreciation of his father, whom he said always had a strong interest in the out-of-doors. Leonard Drey wrote that in 1950, Mr. Drey, having quit his job at Wohl “without knowing what he might do next … began to acquire and manage Ozark timberland. His purpose was to harvest timber conservatively — to regrow a forest while showing this could be done economically.” By 1951, he owned 10,000 acres of badly cut-over land, and further purchases then included 12,000 acres purchased from a tie company. At one time he was the largest private landowner in the state.

Leonard Drey wrote:

In 1953, during a rest break while helping foresters fight a fire, Leo was advised by one of the men of the impending clear-cutting of a 90,000-acre tract owned by National Distillers, a whiskey distillery. This landholding earlier had been owned by the Pioneer Cooperage Co. and managed using a model that relied on single-tree selection. When National Distillers had purchased this land, it publicized its continuing commitment to conservative forestry methods. When Leo learned that National had begun to liquidate their white oak, he traveled to New York, eventually negotiating to acquire the land. Leo retained all of National Distiller’s foresters, headed by Forest Manager Ed Woods and Chief Forester Charlie Kirk (the latter, who had ‘plopped down beside’ Leo to tell him of National Distillers' plans) — men whose understanding of conservative forest management was profound. Today, Pioneer Forest comprises 143,000 acres of land in Shannon, Reynolds, Dent, Texas, Carter and Ripley counties.

And in 2004, Mr. Drey and his wife, Kay, gave Pioneer Forest to the L-A-D Foundation, in that year the largest act of philanthropy in the nation.

William H. Danforth, who knows a thing or two about philanthropy also, thought very highly of the late Leo A. Drey.

“He was a major landowner and he took good care of the land,” Danforth said.

Mr. Drey is survived by his wife, Kay, to whom he would have been married 60 years in November; two daughters, Laura, of Durham, N.C., and Eleanor, of San Francisco; a son, Leonard, of New York City; and his grandson and namesake, Leo, also of San Francisco.

There will be no memorial service. The family requests that, instead of flowers, people send a donation to a charity of one's choice.

Send questions and comments about this story to feedback@stlpublicradio.org.

Support Local Journalism

St. Louis Public Radio is a non-profit, member-supported, public media organization. Help ensure this news service remains strong and accessible to all with your contribution today.