This is a re-posting of an article that originally published in Sept. 2016. It's part of a year-end celebration of some of our most popular work.

Alexis Forman’s rehabbed Benton Park home has everything a typical house has: a living room, dining room, kitchen, bedrooms.

But every now and then, she’ll find strangers out on the street, staring up at the exterior of her brick house — and its dramatically sloping roof.

“Every so often, I’ll walk outside and there will be somebody going, ‘That’s weird,’” she said, laughing.

Forman’s home is what is known as a flounder, or half-house. Typically built in the 19th century, this folk form was once a fairly common housing type in St. Louis. Today, the city has the biggest remaining collection of these historic homes in the country, with 277. But the flounders’ strange shape still catches many residents off-guard.

“The flounder roof form is a triangle — it’s a gleeful, basic geometric unit,” said St. Louis architectural historian and preservationist Michael Allen. “The defining characteristic of the flounder house is the roof slopes from one side of the building to the other — one side is higher by a story or a half story.”

The name, he said, comes from their profiles’ resemblance to the head of a flounder fish, but their moniker isn’t the only fishy thing about them. Historians have only theories as to who first built them and why they took such a curious shape.

Though she’s lived in her home for four years, Forman is none the wiser on these mysteries. But she can answer one question about flounders: what it’s like to live in one.

Amazing porch, awkward arrangement

Forman didn’t know what a flounder was until she came upon it while house-hunting.

“I told my realtor, ‘I don’t understand this house but I think I love it,’” she said.

Much of what she appreciated about the property is related to flounders’ unique history. Like with many flounders, the tall windowless wall that creates the roof peak sits at the edge of Forman’s property line.

As the first homes of craftspeople, laborers and immigrants, the buildings were often the first constructions on a lot, according to Jan Cameron, preservation administrator of St. Louis’ Cultural Resources Office, which has been surveying the city’s flounders.

“It was the first house people built and then later on, often they put a large addition in the front … and made a bigger living space when they could afford it,” she said.

That didn’t happen in the case of Forman’s property, which allowed for the large yard she loves with a front entrance on the side of the house.

But for Forman, the main selling point was the balcony off the second floor master bedroom — another feature made possible by this unique layout. Flounders’ sloping roof lines were often extended out, usually with wood, to form long gallery porches the length of the houses.

Typically, these gallery porches were on the first floor of the homes. But the people who first rehabbed Forman’s home turned what was once a half basement into the first floor, and the first floor into the second floor — creating, essentially, a balcony.

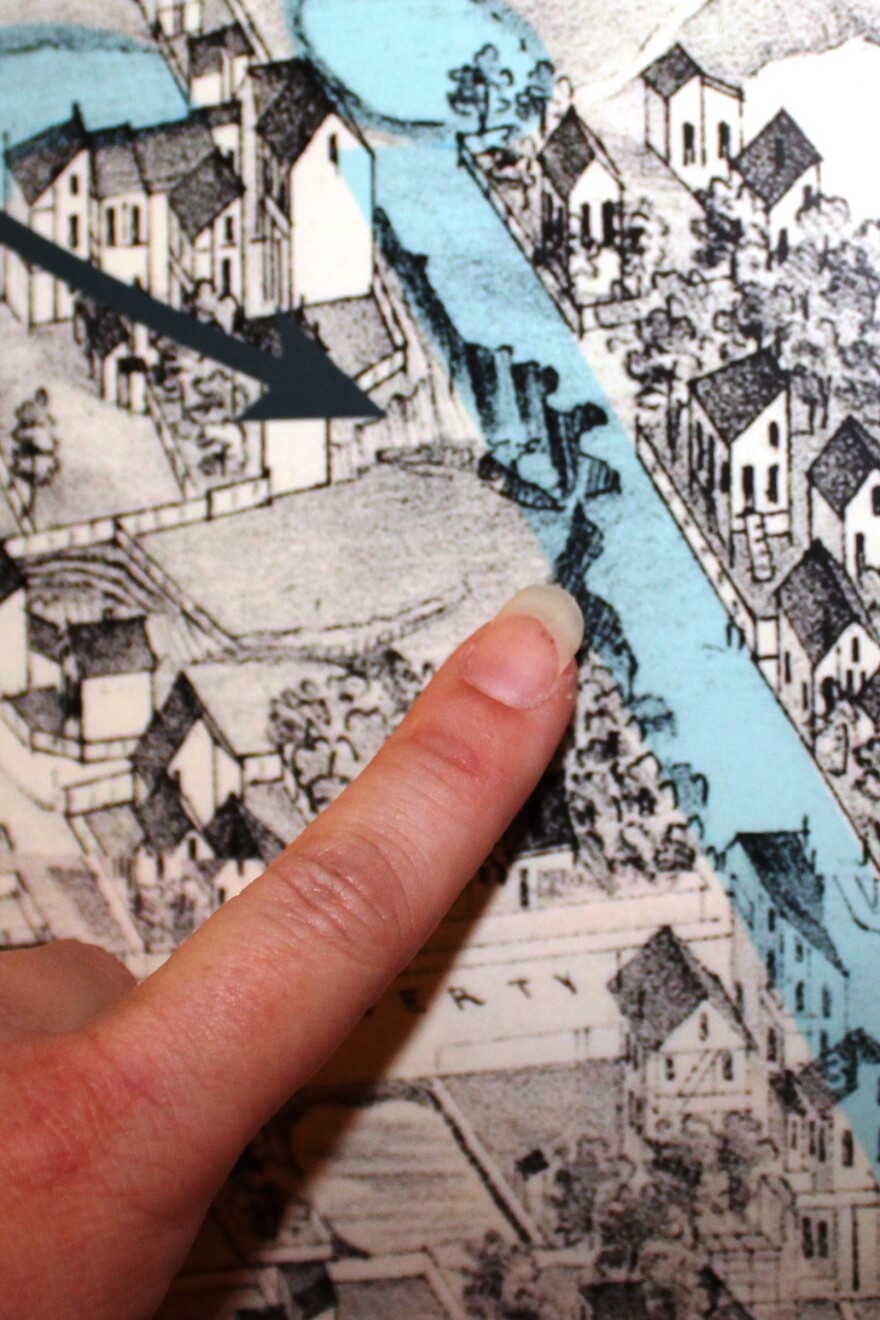

The basement transition also explains why her living room boasts stone walls — the same as the ones seen on the exterior of the building. It’s also made it easy for Foreman to find her home on Compton and Dry's "Pictorial St. Louis" atlas of 1875.

“In my living room, I have a plate of the 1875 map that does have my house on it — it’s plate 36,” she said, pointing. “Crittenden is half a street. My house is obvious — you can see the stairs that cross over the half-basement that go to the first floor, which is now the second floor.”

The half-basement-turned-living room also turned the former second floor into a third floor, which many flounders don’t have. That floor now holds guest bedrooms and a large skylight that illuminates the home. On the second floor is a master suite, complete with en-suite bathroom and a walk-in closet.

The home also holds some surprises.

“There are actually secret cubbyholes in the closets that lead to other storage along the wall,” Forman said. “They did everything they could to use every single inch of space.”

Space is an issue, even with nearly 1,700-square-feet in the home. Forman said the staircase smack in the middle of the house consists of small landings, making it hard to navigate furniture up and down.

“The rooms are strange sizes and strangely arranged, so I had to give away so much furniture because there was no place for them,” she said.

But for all its quirks, Forman said the home is “amazing.”

“I love everything about it, I love that it’s weird,” she said. “It was a perfect 10. It had everything I wanted and more.”

Endangered flounders

Forman is lucky, though: her home had already been rehabbed. Before that renovation, the interior of the home had collapsed in on itself.

While many flounders have been preserved and are occupied, a recent study by the city’s Cultural Resources Office showed dozens are endangered. The office’s Cameron estimates about 60 are currently unoccupied; several are abandoned and in severe disrepair.

That’s why Cameron’s office began its survey of the city’s flounders: it had to know how many were in trouble in order to save them.

Some of the endangered flounders are located in historic districts, making them eligible for tax credits to help with rehabilitation. But many other are not.

The office hopes to get all the city’s flounders listed under a “thematic” designation on historic registries to “be able to offer them assistance,” Cameron said.

“It would be a shame for us to lose them,” she said. “It would really be a loss to our community.”

Cameron said she believes with the right incentives, many people would see the potential in restoring a flounder.

“There is a new small house movement that’s very strong now, these would fit in beautifully with that, plus they are distinctive,” she said. “When you restore the exterior, you have the freedom with what you can do on the inside. There’s a lot of possibility to make it for contemporary living and still retain historic character.”

But Allen, the preservationist, wonders if the challenge to saving flounders is their small size. Some are as small as 500 square feet, and Allen said when they were originally built, they weren’t meant to be “showpieces.”

“These were not grand homes,” he said. “It’s not the kind of house if you had wealth you would want to build. It’s the type of house you’d build to have a house.”

Records show St. Louis’ flounders can be traced back mainly to German immigrants, but architectural historians have not been able to find a direct connection back to German housing styles. Neither have they been able to find why exactly the builders chose a triangle form.

“Mostly, it’s a simple roof form that effectively sheds water,” Allen said. “One architectural historian opined that the roof form was preferred because it required the fewest cuts. You did not have to be a skilled carpenter to essentially lay pieces of wood into slots in the brick walls and put a roof across it. It was a quick and easy house to build and an affordable house.”

Allen said that’s perhaps reason enough.

“The origin and background of the flounder house is as clear as the motivation of John Wilkes Booth,” he said. “I think it’s something we’re always going to be debating and figuring out, but never have a definitive answer.”

Favorite flounders

But perhaps the mysteries behind these flounders are part of their appeal. Cameron, for one, said she would love to live in one of these “charming” and “adorable” flounders.

She’s particularly fond of a wooden Benton Park structure that actually consists of two flounders butting up against each other. Only about five percent of the city’s remaining flounders are frame, or wood, buildings.

“This house is one of the oldest in our survey,” she said. “This building appears on the Compton and Dry Atlas of 1875, but before that actually, because it has an addition on the back -- another flounder -- also on the 1875. So it was probably more like 1860 in the front.”

Meanwhile, Cameron’s colleagues have their own favorites, illustrating the variety among flounders. Co-worker Bob Bettis said his favorite is an “extremely ornate” detached brick flounder in north St. Louis. Andrea Gagen likes a more “high-style” version of a flounder, with hipped roofs in the Italianate style. These roofs still have the tall wall, but the roof slopes back toward the front, instead of continuing to the side.

Their appreciation of flounders is shared by St. Louis resident Josie McDonald, who hopes to find proof that her Compton Heights home is itself a flounder.

“It’s not a dramatic flounder, not a 45-degree angle,” she said. “But we do feel it has a tall wall and then that the roof line scoops down to an adjacent wall, and we do think, yes, it is a flounder.”

But she said she’s also interested in finding other like-minded lovers of these unique homes.

“If you’re a St. Louisan like I am, it’s just a curiosity you want to know more about,” she said. “It’d be kind of nice to identify with other people who think there’s some kind of value to living in a flounder.”

Forman certainly thinks there is, and she’s even become friends online with a few fellow flounder aficionados. She also has gone “flounder fishing” in a Pokemon Go-esque attempt to find all the St. Louis flounders and talking to owners who don’t know they live in a unique structure.

“They’re just neat, they’re an interesting part of our history,” she said. “There seems to have been a specific time when they were built and then they stopped building them. I wish more people were more curious about it so we could answer these questions.”

Follow Stephanie on Twitter: @stephlecci