It’s the early to mid 1800s in Missouri. The state’s German population is seeing an increase, especially in the cities of St. Louis and Hermann. Many are traveling to the U.S. to seek a better life, free of injustice from German rulers. Amongst those immigrants is Arnold Krekel.

Krekel’s story is not known to most St. Louisans. He arrived in America at 17 years old and eventually became a federal judge. He was also one of many from his region to fight for the abolition of slavery in Missouri.

Krekel’s legacy might be unknown to the masses, but a symposium on Feb. 23 will explore his legacy and the role of he and others in the abolition of slavery. "Faces of Love: Symposium on the History of German and African Americans in Missouri" is being produced by Gitana Productions, an African-American led organization. The focus of the event is to highlight the German leaders who settled in St. Louis, St. Charles and Hermann.

Taking A Stand

Some of the German immigrants came to Missouri from Prussia, said Sydney Norton, an assistant professor of German at St. Louis University and a speaker of the symposium. Others came from Bavaria, Baden and other German states.

She said many of those immigrants weren’t able to own property and didn’t have the right to vote in their homeland. Norton said many German settlers recognized slavery as a much harsher form of injustice and decided to speak out on the matter.

“Along the Missouri River, a lot of the people were slaveholders,” Norton said. “This German group in Hermann were not, and they started a newspaper there and wrote all sorts of articles against slavery.”

The Hermanner Wochenblatt was founded in Hermann by Germans Carl Strehly and Eduard Muhl in 1845. The newspaper, Anzeiger des Westens, was published by immigrant Henry Boernstein, an Austrian. Both papers were not only notable for their anti-slavery articles, but also included copies of antislavery literature. The Wochenblatt published installments of "Uncle Tom’s Cabin," for 26 weeks.

Still, abolitionist policies were often dangerous positions to take, especially for newspaper reporters and editors.

“When you took a position, you did that knowing your life may be in danger, and you may not be readily accepted in the community,” said John Wright, a local historian and author.

Wright said that danger was heightened in 1837 when Elijah P. Lovejoy, the editor of the Alton Observer, was killed by an angry mob. Lovejoy was known for his abolitionist stances.

Krekel And Turner

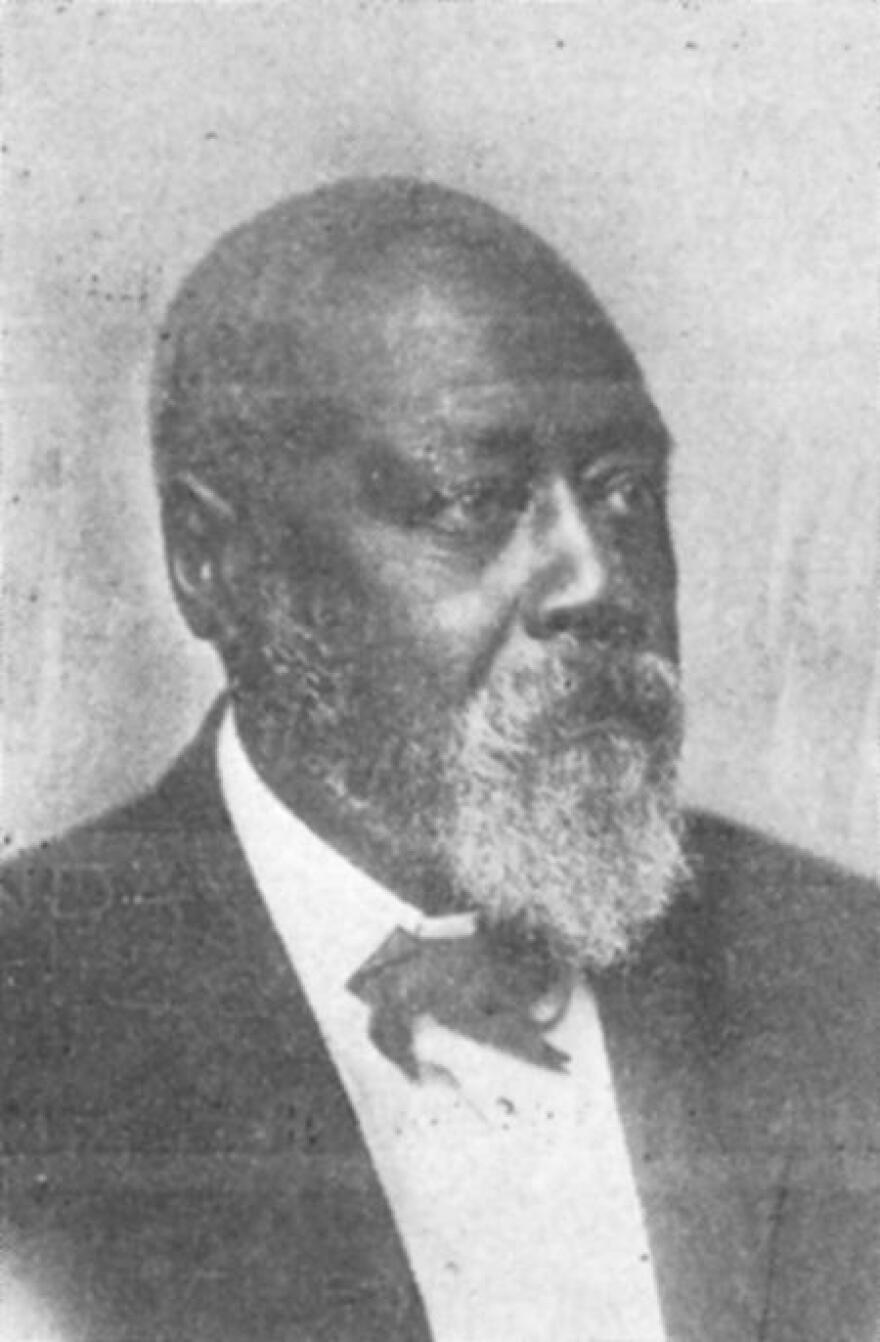

Krekel founded a newspaper, too: the St. Charles Demokrat began publication in 1852 and ran through 1916. The paper published anti-slavery articles and editorials. And Krekel helped establish the Lincoln Institute — now known as Lincoln University — working with other abolitionists including James Milton Turner, a freed slave from St. Louis.

That partnership will be previewed at the symposium and will be the focus of a play in June. The play was written by Cecilia Nadal, the founder and executive director of Gitana Productions.

“It’s very impressive that this group of German abolitionists could fight for what they believed was important,” Nadal said. “Beyond just the fact that they’re German and just the fact that they were helping slaves is the issue of standing up for what you believe in.”

St. Louis actors Garrett Bergfeld and Abraham Shaw will portray Krekel and Brown respectively. The play will also highlight the contributions of several other German abolitionists including Boernstein and Friedrich Münch.

Nadal hopes the symposium and the play will open up to deeper conversations surrounding racial equity.

“This is a town where we’re split by housing, we’re split by economics, we’re split by race,” Nadal said. “How is it that we get past that? It’s not through intellectual discussions, it’s through actual interpersonal engagement.”

The symposium will run from 2-5 p.m. Saturday. The June production will run from June 20-23.

Follow Chad on Twitter @iamcdavis

Send questions and comments about this story to feedback@stlpublicradio.org

Correction: Henry Boernstein is Austrian. A previous version of this story said he was German. Also, most German settlers in Missouri did not come from Prussia as previously stated. They also came from Bavaria, Baden and other areas.