It’s Tuesday, the day when we poke our heads out of the offices of St. Louis Public Radio and review some of the other stories brewing in the economy that have piqued our interest.

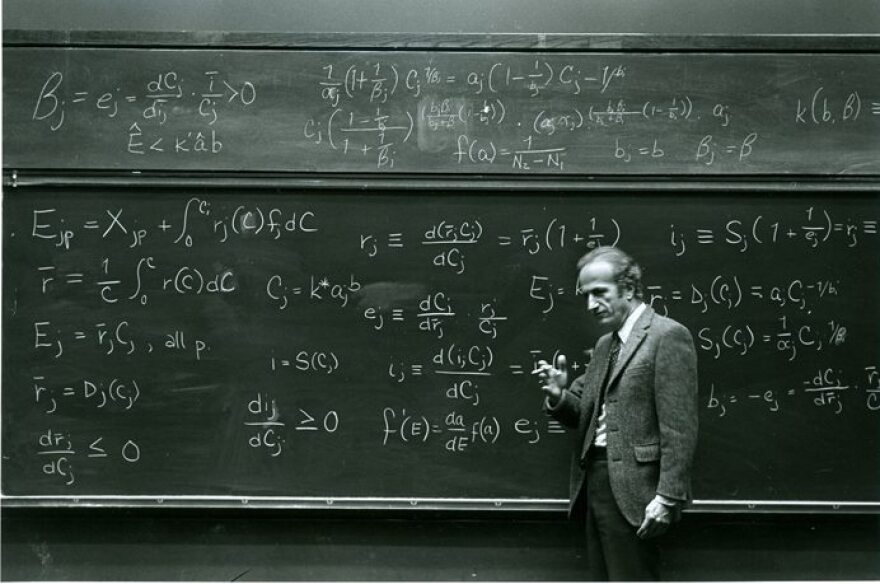

First up is news that a very important economist has left this earth. Nobel Laureate Gary Becker died on Saturday. He is most notable for his economic theories that tried to explain human behavior, tackling questions that went way beyond supply and demand. The University of Chicago professor studied things like crime, racial discrimination and even romance.

One of his earliest -- and most notable -- works looked at “The Economics of Discrimination,” in which he showed that workplace discrimination is less likely to happen in highly competitive industries where employers need to hire the most efficient workers. Employers lose if they let bias influence who they hire. And because of that, the need for good workers and productivity will trump bias.

The premise of behind all his work is that human beings make rational decisions, and each person in society is his or her own rational economic agent. With that understanding, Becker explained how even drug addicts make decisions on whether or not to use by doing a cost-benefit analysis: Is today’s high worth tomorrow’s need for another hit?

The New York Times had an appraisal of Becker’s work from Justin Wolfers, a professor economics and public policy at University of Michigan. He wrote:

“Professor Becker’s Nobel Lecture was his sharpest defense against these charges, and he recounted how he “tried to pry economists away from narrow assumptions about self-interest.” Instead, he said, “behavior is driven by a much richer set of values and preferences.” Purposeful decision making doesn’t mean that behavior is driven by financial concerns, but rather, in his view, “individuals maximize welfare, as they conceive it, whether they be selfish, altruistic, loyal, spiteful or masochistic.”

There’s also a very charming rundown of some of Becker’s more well-known research in PolicyMic.com, which tags Becker as the “godfather” of what has come to be known as Freakonomics.

Our heads are bowed in memory of Gary Becker today. He truly enriched the “dismal science.”

A kind of “Beckerian” situation

Smokers in Kansas City’s public housing developments have received some bad news -- bad news from their perspective. The Kansas City Housing Authority has approved a smoke-free policy. This new policy doesn’t just restrict smoking in common areas of the building or near entrances. It bans all smoking. Everywhere. Even in individual apartments.

The Kansas City Star interviewed several public housing residents who were nonplussed, to say the least. One Juia Leggett stated it most succinctly: “I want the right to smoke in my apartment. That’s the bottom line.”

According to the article 40 percent of KC public housing residents smoke. And apparently the majority of them were unaware that the policy was even under consideration until a short time before the April 16 vote on the new policy. The ban is set to go into effect January 1, 2015.

Kansas City isn’t the only place where public housing bans smoking everywhere. But it appears to be first in the Midwest.

The policy isn’t really intended to get people who do smoke to limit their habit to a certain location. As I mentioned, the policy also applies to doorways, courtyards and other public housing grounds. The goal is most evidently to get people to quit smoking altogether.

This has many people concerned beyond the “my home is my castle,” argument. Quitting smoking is really hard. And if people are having a hard time quitting and end up breaking the rules, then what? The Black Health Care Coalition has always weighed in on the issue because 80 percent of the KC Housing Authority residents are African-American. The organization’s executive director told the Kansas City Star that her group is concerned about “the potential that residents in public housing may be evicted and facing homelessness due to nicotine addiction.”

So, how would Gary Becker examine the situation? Will people stop smoking in their public housing apartment, knowing there is a risk they could get kicked out? Or is the threat of homelessness enough to help people quit smoking?

Closer to home

And speaking of a cost-benefit choice many of us make every day… consider the parking meter.

For years meters only took coins. It made sense back in the glory days when a penny would buy you five minutes and quarter a full hour of parking time. But then parking rates went up and up. And now, in some places, it will take at least six quarters to pay for that hour of time. Who has that many quarters on them?

Other cities have long ago adopted modern parking meters that accept credit cards, and some even accept dollar bills. St. Louis is just now dipping its toe in the waters.

Our friends at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch have been doing a great job chronicling the region’s attempt to find the best parking meter solution. And by great job, I mean those articles make me smile at the hand wringing and genuine ire over what system to use and why.

And the best part? People are downright confused over how to use these new meters that are scattered about the city and county on a trial basis. It turns out, they’re confused for a reason: there are four different vendors with four different meters that are being tried out. They have different types of technologies and different displays. Some are for single spaces and some work as one meter for two spaces.

The ones that are intended for two spaces had arrows pointing in the wrong directions, so people were getting tickets for paying for the wrong space.

I think met one of those meters one day. I know I was very confused about which space I was paying for. I didn’t get a ticket for my mistake, luckily, but apparently plenty of people have.

The test program ends in July in the city. People can take a survey through the city of St. Louis' treasurer's website to give feedback on what meters to use.

In the meantime, plenty of people will be pulling to spaces with the new meter and start to make the economic calculation of whether or not it’s worth trying to figure out how the meter works, or just not paying at all and getting a ticket.