William H. Danforth II, who took the reins of Washington University during a period of financial uncertainty and cultural strife and helped defuse animosities by reading bedtime stories to students, has died. He was 94.

"I believe that Washington University is one of this community's contributions to mankind,” Danforth said in a Founders Day speech in 1972, a year after he became chancellor. “A successful university is a noble institution.”

Achieving nobility required a lot of money. Danforth obliged by establishing 70 new faculty chairs and increasing the university’s endowment to nearly $2 billion, the seventh-largest in the nation.

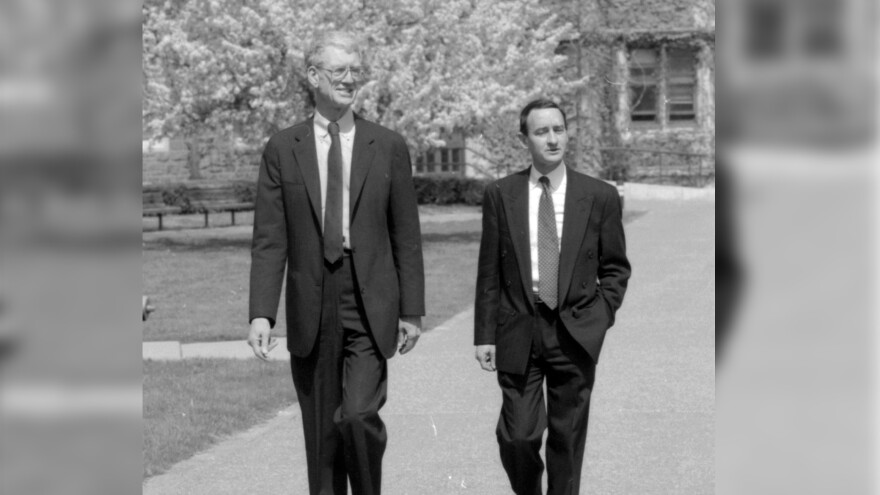

Danforth, who began his career as a cardiologist, led the university’s metamorphosis from a local college to one of the top 25 universities in the nation.

“Chan Dan,” or “Uncle Bill,” as he was fondly called by students for 24 years as Wash U's chancellor, died Wednesday, Sept. 16, in St. Louis.

Danforth was one of the longest-serving university heads in the nation.

"When I became chancellor, the students seemed so young; today the parents also seem young; no one should stay until the grandparents look young,” he said in a St. Louis Post-Dispatch excerpt from the letter announcing his retirement.

Paying a debt

Danforth was the grandson and namesake of the founder of Ralston-Purina. His grandfather launched the animal feed business in 1894. His father, Donald Danforth Sr., grew the company from a small, family-owned business into one of the 75 largest companies in the nation.

He chose not to go into the family business.

When he was about 15, Danforth’s parents thought he could benefit from spending time with a doctor who cared for poor children in the Appalachian Mountains. Then he read "An American Doctor’s Odyssey" by Victor Heiser. He was hooked.

Danforth shared his career decision and other life notes in an oral history for Washington University’s Becker Medical Library in 2007.

When he graduated from Country Day School in 1944, World War II was still raging. He entered a military training program at Westminster College in Fulton, where his service duties were minimal and he was able to take a premedical course.

When the war ended, he transferred to Princeton, earning a bachelor of arts degree in 1947, then entered Harvard University Medical School.

In 1950, during his last year of medical school, he married Elizabeth “Ibby” Gray, who had recently graduated from nearby Wellesley College. The two St. Louisans returned home after his graduation from Harvard in 1951.

After interning at Barnes Hospital, he returned to the military.

“I owed the country something,” Danforth said. “I felt that I hadn’t done what a young man ought to do; I was kind of happy to do something in a war.”

He headed to Korea as a medical officer on Navy destroyers. Their job was to keep the North Korean and Chinese boats out of the area. It seemed like playing at war, he said — until the evening they blew up a Korean fishing boat.

“I thought to myself, ‘These are probably men out trying to catch a few fish to feed their kids,’ and that changed my whole idea about war,” he said. “It made me very close to being a pacifist from then on.”

When he returned to the U.S., Danforth worked in a Maryland Navy hospital before resuming his medical training in St. Louis at Barnes. He specialized in cardiology and, in 1957, became a faculty member at Washington University. There he stayed for the remainder of his career.

As faculty, Danforth did basic research with Carl Cori, who, with his wife, Gerty, earned the Nobel Prize in part for their development of diabetes treatments. Danforth also did rounds at John Cochran Hospital for veterans.

University administrators took notice of his good work and in 1965, persuaded him to join their ranks as vice chancellor for medical affairs. In a story he told often, one of his young daughters was unimpressed by the move.

“Well, she was talking with a friend about their fathers and the friend said, ‘My father makes toys,’ and my daughter quickly decided not to compete and she said, ‘My dad doesn’t do anything; he used to be a doctor and make people well, and now he just goes to meetings.’”

Many of those meetings were in the African American community. He was on the board of the north St. Louis clinic, a federally funded program. The board was made up of Black people from the community such as activist Ivory Perry, as well as white “establishment figures.”

“After the first meeting or so, I was the only white guy attending the meetings,” Danforth said.

Into the fire

He picked a tumultuous time to join the front office. It was the mid-1960s, the heart of the civil rights movement and the heat of student rage against social injustice.

Students had begun demanding that Wash U sell assets in businesses that invested in South Africa. That country’s apartheid policy prompted protests for decades. But it was the Vietnam War that provoked violent protests. The campus erupted after National Guard troops killed four students during a war protest at Kent State University.

Danforth stood alongside then-Chancellor Thomas Eliot as the university was rocked by protests. Black students challenged the university’s curriculum and campus policing. Thousands of students occupied buildings. Before it was over, a campus ROTC building was burned to the ground. A second ROTC facility, built off campus, was bombed.

“I started out very sympathetic to the radical people,” Danforth said, but he disdained the violence. And Washington University was fighting violence on two fronts.

Danforth was with Eliot when St. Louis County police, in full gear, began “tracking” students on campus. They were ordered to leave. Police threatened not to come back if needed.

Being a native St. Louisan gave him a unique perspective to help craft the university’s response to the unrest, Danforth believed. Eventually, the university made minor divestments in South Africa, a Black studies program was established, and the war ended.

The turbulent decade had taken its toll on Eliot, and he began looking for his successor.

“Tom Eliot sort of set me up for it,” Danforth recalled in his oral history.

Months earlier, Eliot had appointed him to head a committee to look at the future of the university. It was, indeed, a setup.

Bedtime stories

On July 1, 1971, Danforth became Washington University’s 13th president.

He inherited smoldering tensions, but he had a secret weapon: He “just liked people.”

And people liked him.

Soon students were calling him “Chan Dan” or “Uncle Bill” — to his delight.

Many of the nearly 60,000 students who graduated during his tenure got to know him personally.

He was a regular at football games. Once, he accepted an invitation to be Santa at a dorm party, though his long, lean frame and smile-creased face seemed more suitable for a role in a spaghetti Western.

His voice also carried a frontier flavor, perfect for telling bedtime stories, which some students asked him to do, and which he obliged. He favored "Thurber Fables," the retelling of traditional fairy tales, because they were fun and carried a moral.

The money man

Equally challenging was the university’s finances.

A self-described “numbers guy,” Danforth became a prolific fundraiser. He established 70 new faculty chairs and built a $1.72 billion endowment. He made the “big, big decision” to stay in the city and change the campus landscape, overseeing the funding and construction of dozens of new buildings.

"He was a fantastic money-raiser," his longtime friend and former assistant Katherine Drescher told the St. Louis Beacon in 2013. "He would go back and back to people. And, he'd say, if you can't give any money, I'll take the couch in the living room. He would say it in the nicest possible way."

In 1983, Danforth spearheaded the $300 million Alliance for Washington University campaign. It concluded in 1987 and raised a record-setting $630.5 million.

Cynics credited the Danforth Foundation with fueling his successful fundraising efforts, the Post-Dispatch reported in 1986. Danforth was the foundation’s chair as it funneled more than $200 million to the university during his time as chancellor.

With his usual equanimity, Danforth said of the criticism: “I haven't really tried to respond.”

His leadership attracted tens of millions of dollars in new federal research awards and funding collaborations. One of the most lucrative was with Monsanto. The company agreed to fund biomedical research in return for the right to license resulting patents.

In 2011, Danforth oversaw the family foundation’s final award, $70 million to the project that would begin the second act of his life: the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center, a research institute named in honor of his father.

In defiance, in demand

A year after he became the new chancellor, Danforth, along with P. Roy Vagelos, then head of the biochemistry department, made a major change despite faculty objections. They created the Division of Biology and Biomedical Sciences, linking programs at the medical school with biology and anthropology.

The new division was his first major fight; it would not be his last.

Washington University had close ties with area businesses. Danforth strengthened those ties, but some said he made them too strong.

In a 1989 Post-Dispatch story, some faculty members expressed concern that he tilted the board toward conservatism with corporate executives “who worship the bottom line.”

He drew additional criticism for how funding was spent.

Danforth relinquished two schools he deemed too weak to warrant the expense. In 1989, the school’s nationally known sociology department was phased out, and he closed the 130-year-old dental school.

The decisions drew local ire, but by now, Danforth had built a national reputation. Other organizations, such as the National Institutes of Health, wanted his talents to be used to benefit them — just as he’d done for Washington University.

Three consecutive administrations considered him to head the NIH: Ronald Reagan's, George H.W. Bush's and Bill Clinton's. He declined all three, the second on principle.

He was asked by Bush White House aides for his position on abortion and using fetal tissue for research. The administration opposed both. Danforth considered the question to be an improper “litmus test,” the New York Times reported.

Whatever success he achieved, he attributed to the people around him. It was no gratuitous claim. During his tenure, people associated with the university won 10 Nobel Prizes and two Pulitzers.

Three years before his retirement in 1995, Washington University hosted the first-ever presidential debate with three candidates: President George H.W. Bush, Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton and independent candidate H. Ross Perot.

By the time he retired in 1995 and transitioned to chairman of the board, his accomplishments were legion and lauded nationally.

“During my time as chancellor, I didn’t have a grand plan to initiate a lot of things,” Danforth said in 2007. “What I did was to try and get behind the things that I thought were good that I thought people were trying to do.”

Elusive retirement

With the blessing of his successor, Mark Wrighton, Danforth moved seamlessly from chancellor to board chairman and chancellor emeritus. But he was still looking for more to do and soon found it.

In 1996, he was appointed "settlement coordinator" to help negotiate an end to the St. Louis school desegregation case. Three years later, he shared a FOCUS St. Louis award with Minnie Liddell, an African American mother who filed the original desegregation lawsuit in 1975.

It was the same year that he and civil rights attorney Frankie Muse Freeman led a task force to oversee the landmark settlement that ended segregation in the St. Louis public schools. In 2006, the pair also led an advisory committee to analyze and improve the St. Louis schools.

Ultimately, Danforth decided St. Louis needed to help feed the world. He established the Danforth Plant Science Center.

At age 72, he teamed up with Peter Raven, then head of the Missouri Botanical Garden, and Virginia Weldon, who had recently retired from Monsanto, to discuss plans for the next great Green Revolution.

Despite earlier efforts, Danforth said in his 2013 St. Louis Award acceptance speech, "a billion people are undernourished and, on average, a child dies of malnutrition every six seconds."

As founder and board chair, he grew the Danforth Center into the world's largest independent nonprofit plant science research organization.

Danforth waded into the controversy of genetically modified crops for animal and human consumption. He noted in a 2000 Post-Dispatch op-ed that “the potential benefits of genetically modified crops far outweigh the potential risks,” adding that the Danforth Center was “the result of my convictions, not the cause of them.”

His convictions were equally firm on the contentious issue of stem cell research. He actively promoted a 2006 Missouri constitutional amendment to protect stem cell research because he knew that the opposition was based primarily on religious beliefs, not scientific research.

“This stem cell opposition, the most unpleasant thing about that is the combination of religion with the right wing of the Republican Party,” he said in 2007. “I don’t like [mixing politics and religion].”

'I was very lucky'

William Henry Danforth II was born April 10, 1926, in St. Louis, the eldest child of Dorothy Claggett Danforth and Donald Danforth, a business executive. He was the grandson of the first William Henry Danforth, founder of the animal food giant Ralston Purina. His grandfather was a graduate of Washington University's Manual Training School and mechanical engineering program in the 19th century.

“I did not grow up in a family that spent much time talking about intellectual things or cultural things,” the intellectual and cultured Danforth once said.

His myriad honors included being named "Man of the Year" in 1977 by the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. In 1994, along with his brother, Sen. John C. Danforth, he received the Right Arm of St. Louis Award, the highest award given by the Regional Commerce and Growth Association (now the St. Louis Regional Chamber).

When Ibby, his wife of 55 years, died in 2005, Danforth said in her Post-Dispatch obituary, "I was very lucky, as I married young and married well.”

A daughter, Cynthia Danforth Prather; his sister, Dorothy Danforth Miller, and a brother, Donald Danforth Jr., died earlier.

In addition to his brother, Danforth’s survivors include two daughters, Maebelle Anne Danforth of St. Louis County and Elizabeth G. Danforth of Ladue, Mo.; a son, David Danforth of Clayton, Mo.; 13 grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren. A fourth child, Cynthia Danforth Prather, died in 2017.

Services are pending.