On Friday, Governor Jay Nixon postponed the execution of an inmate that was set for later this month. That execution was going to be carried out using propofol, a common anesthetic that has never been used in a lethal injection before. So why the change in plans?

Part of why anesthesiologists like to use propofol is because it acts fast and has few side effects. In fact, propofol is the most widely-used anesthetic in the US. It’s used on average 140,000 times per day, for everything from colonoscopies to open heart surgeries.

Washington University anesthesiologist Dr. Ellen Lockhart said on a busy day, she’ll use it 10 to 12 times.

"If the patient’s going to have general anesthesia, I use it every time," Lockhart said. "Almost every time.”

But later this month, Missouri had planned to use propofol for a very different purpose: to put someone to death. It would have be the first time the drug has been used for lethal injection.

It's used on average 140,000 times per day, for everything from colonoscopies to open heart surgeries.

About 90 percent of the U.S.’s propofol comes from Europe. And that’s important, because the European Union is really against the death penalty.

“The European Union at the moment already has legislation in place that prevents export of certain chemicals that can be used for capital punishment,” Maja Kocijancic a spokesperson for the European Union, told us.

She said the EU is considering amending that law to add propofol to the list of restricted chemicals.

“Supplies to hospitals, for example, in the U.S. would continue to be possible," Kocijancic said. "There would need to be an export authorization, but the export could go ahead.”

She said an outright ban on propofol exports would be unlikely.

“But given the steps that we would have to go through, the net effect would still be the same,” Matt Kuhn, a spokesperson with the German drug manufacturer Fresenius Kabi said. His company makes most of the propofol used in U.S. hospitals.

“There would be a tremendous reduction in the availability of product, and that would lead to a shortage,” he said.

Kuhn said his company would have to get an export license for every shipment of propofol it wanted to send. And that process would take three to six months every time.

“It would be significant enough to create a lack of availability of product that would put both clinicians and patients in a very difficult spot in the U.S.,” Kuhn said.

Because of the potentially serious consequences, his company, Fresenius Kabi, has already taken steps to keep propofol from being used in lethal injection. The company requires all of its U.S. distributors to sign a contract saying they won’t sell to departments of correction.

'Please -- Please - Please HELP'

But about a year ago, one of Fresenius’ suppliers made a mistake. The supplier was supposed to block out all of the departments of correction from their sales list, but they missed one. They sent a container of propofol to Missouri’s Department of Corrections, who would have liked to use it in two upcoming executions.

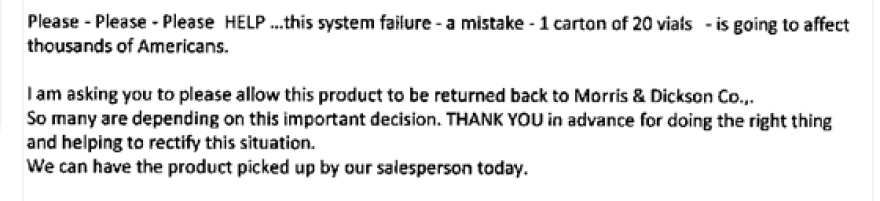

Once the supplier realized their mistake, they sent frantic emails to the state, pleading with them to give it back.

Here’s one from last November:

For 11 months, the Missouri Department of Corrections held onto the shipment. But on Oct. 9, following an open records request by the American Civil Liberties Union, the state gave in. The department said it was returning Fresenius’spropofol to the supplier.

Missouri said it would still go ahead with the executions though, because it also had propofol that was made in the U.S. But most manufacturers have joined Fresenius in condemning propofol’s potential use for lethal injection -- and also require suppliers to not sell it to states who would use it that way.

That raises the question: How did Missouri get ahold of propofol when it wasn’t supposed to?

We’ve reviewed 180 pages of Department of Corrections documents obtained through a sunshine request by the ACLU.

An 'Unauthorized Distributor'

According to those records, the Missouri Department of Corrections bought 100 vials -- about half a gallon worth -- of propofol in June of this year. That propofol was made by Hospira, the only U.S. manufacturer. We reached out to the company, and asked if they knew Missouri was planning to use their product to carry out an execution.

In a statement, a Hospira spokesperson wrote:

“We have been provided information suggesting that the state of Missouri has a supply of Hospira propofol, and that the state purchased it from an unauthorized distributor.”

That 'unauthorized distributor' was a supplier named Mercer Medical.

In April, a sales representative from Mercer named Chris Rudd emailed the Missouri Department of Corrections to convince them to use his company as a vendor. In that email, Rudd said Mercer specialized in “the delivery of products that have gone into short supply in the market.”

One of the drugs in short supply? Propofol. A five pack of 20-mL vials for $125. A few months later, the Department of Corrections bought the propofol from Mercer.

St. Louis Public Radio called Rudd to discuss the sale. Rudd sounded very nervous when he picked up, told us he was extremely busy at the moment and that we would have to talk to their communications department. When we asked if he was authorized to sell Hospira’spropofol, he hung up.

Rudd, and his company, Mercer Medical, never got back to us. The Department of Corrections and the governor’s office have also ignored our requests for comment on how the state got Hospira’spropofol.

Hospira has asked for its drug back.

A Reversal

As recently as Monday, a flustered Nixon told us the state was moving forward with the executions, as long as the courts didn't intervene.

“We are very cognizant of the attention this is drawing and the potential challenges that are out there," Nixon said. "But we are resolute that the issue should be one that is played out by a court of law so that the consistency of this can be maintained.”

But in a reversal on Friday, Nixon announced that he had directed the department of corrections to hold off on this month’s execution. He also said he’s directed the state to modify its execution protocol to include a different form of lethal injection.

But finding a replacement drug might not be so easy. With most drug companies opposed to having their products used in executions, there aren’t a lot of options out there.

Follow Chris McDaniel on Twitter: @csmcdaniel

Follow Veronique LaCapra on Twitter: @KWMUScience