Norm London, as he was wont to introduce himself, was a criminal attorney who represented the powerful and the powerless with equal vigor. For 40 years, he defended some of the area’s most famous and infamous citizens before taking his formidable reputation to the federal Public Defender’s Office in St. Louis.

“The legal representation in our office is on par with anything you could go out and buy,” said Lee T. Lawless, who succeeded Mr. London as federal defender. “His name being associated with this office got that message across.”

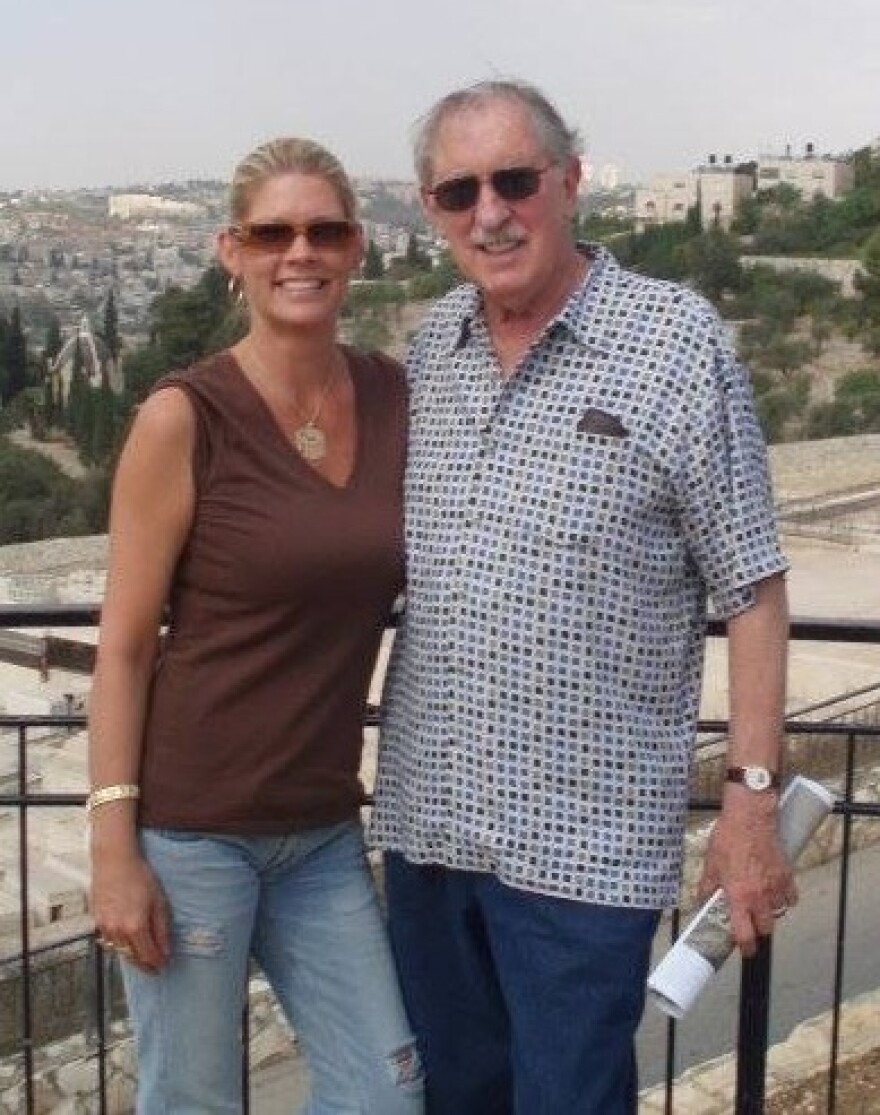

Mr. London, who had lived in Richmond Heights for more than 40 years, died on Saturday, March 1, at Missouri Baptist Medical Center in Town and Country. He succumbed to pneumonia, congestive heart failure and renal failure said his wife, Michelle London. He was 83.

Services for Mr. London will be Thursday, March 6, at Congregation B'nai Amoona.

Mr. London’s move to the public defender’s office meant a considerable drop in income. He didn’t mind.

"I decided it's payback time,” Mr. London told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch when he took the job in 1995. “I will enjoy practicing criminal law for one client who pays the bills - the government."

The defense

Norm London took cases Perry Mason may have been loath to touch. The ‘70s and ‘80s were particularly fertile times for him.

In 1973, 10 law enforcement officers were indicted on 42 counts of federal civil rights violations for raiding the wrong homes in an attempted drug bust in southern Illinois. Mr. London was co-counsel with David P. Schippers in the case that came to be known as the “Collinsville 10.” All were exonerated.

"It was an incredible feeling," Mr. London told the Post-Dispatch, "to hear a clerk read the verdict `not guilty' 42 times.”

Members of the Busch beer dynasty were his clients on more than one occasion. During the 1970s, he secured probation for Peter Busch, who was accused of manslaughter in the shooting death of a friend; and he successfully represented August A. Busch IV on charges that he tried to run down two St. Louis undercover narcotics detectives in 1986. He won an acquittal for Donald E. Lasater, then head of Mercantile Bank, on four counts of perjury before a grand jury. He was co-counsel for Pantera’s Pizza founder Robert C. Walker, who cried when he was acquitted in 1988 of sexual-assault charges.

His clientele included bona fide mobsters like Anthony Giardano, John Vitale and Jimmy Michaels.

He didn’t always “win,” but his work always made a difference.

Like the 1970s case of Johnnie Lee Brooks, who was convicted of brutally blinding a young woman, Wilma Chestnut, during a robbery to keep her from identifying him. Reportedly, convinced of Brooks’ innocence, a priest persuaded Mr. London to defend Brooks. He drew a 70-year sentence, but escaped the death penalty and later received a lesser sentence after a double jeopardy ruling.

Mr. London took a case during the AIDS epidemic that may have helped set the stage for different verdicts in the future. He filed suit on behalf of a Washington University student with AIDS who, in 1988, had been barred by the university’s dental school from clinical work. In 1991, the courts ruled in the school’s favor.

It was no secret that Mr. London had an all-time favorite case: the theft of Mr. Moke, a “talking” chimpanzee who was the star of the “monkey show” at the St. Louis Zoo.

The zoo bought the chimp from a Florida man who had taught him to say “no” and “mamma.” Four days before Christmas in 1959, the chimp’s former owner broke into the ape house and liberated Mr. Moke. The two remained at-large until Mr. Moke -- or his former owner -- contacted Mr. London, who arranged for the chimp to turn himself in. Mr. Moke went back to performing ,and Mr. London got the owner off with 18 months’ probation, a little less time than he and Mr. Moke had been on the run.

Lawyer for life

Mr. London graduated with a bachelor’s degree from Washington University in 1952, and earned his law degree there two years later. He attended law school at the same time that his older brother, Stan, who became the team surgeon for the Cardinals, was in medical school at the university.

Following graduation, he clerked for a federal judge, and then worked briefly for a downtown law firm. But he longed to be in the courtroom. He began working with Mark Hennelly and Morris Shenker, then two rock stars of criminal law.

He soon joined those heady ranks. In the courtroom, Mr. London stood out – figuratively and literally. He was 6-feet-5, with a regal bearing that belied his ability to cause apoplexy in prosecutors.

As he began to establish his career, he helped to organize the St. Louis Police Officers Association. Through the years, however, as often as not, he found himself on the opposite side of the courtroom from law enforcement. No matter where he sat, he retained the officers’ respect.

He later inherited Hennelly’s law practice and in 1960, he launched London, Greenberg and Pleban. The firm dissolved in 1988, and he began running his own office with four other lawyers.

In 1995, Mr. London retired from private practice to lead the Federal Public Defenders Office for the Eastern District of Missouri. He headed the office for more than 10 years.

Several years ago, Mr. London returned to private practice, becoming of counsel with Rosenblum, Schwartz, Rogers & Glass, P.C., a position he retained until his death.

“He wanted to keep his hand in,” said N. Scott Rosenblum, president and principal with the firm. “Just having him around was helpful; he was just an incredible resource. He was extremely smart, compassionate, dedicated and didn’t suffer fools.”

Mr. London served as the Missouri attorney general's representative to the Committee to Review Criminal Laws of Missouri; as special adviser to the Committee to Draft Pattern Instructions in Criminal Cases, adopted by the Missouri Supreme Court; and as a member of the state's Urban Violence Task Force.

He was elected to The Order of Coif, was a Fellow of the American College of Trial Lawyers, a member of the national executive committee for the American Board of Trial Advocates, and the former chair of the Criminal Law Committee of the Bar Association of St. Louis. Since 1981, he had been an adjunct professor at Washington University School of Law, from which he had received a distinguished alumni award.

On top

Norman Sidney London was born Sept. 6, 1930, in Springfield, Ill. He was the youngest of Maurice London, a Washington University-trained dentist, and Mary Kohn London’s three children.

He was a self-described fiscal conservative and social liberal, who never stopped sharing his opinion on issues of the day.

“He was a very, very bright guy,” Lawless said. “He kept on top of things.”

Mr. London was preceded in death by his parents, a sister, Thelma Riley, a granddaughter Meredith Littlejohn, and his former wife, Carole London Christianson. Another marriage ended in divorce.

His survivors include his wife of 15 years, Michelle Godi London, three children, Stefanie (Steve Littlejohn) London, Gary London and Brittany Marquardt, all of St. Louis; a brother Stanley (Jackie) London, M.D., Ladue, and three grandchildren, Chaz Littlejohn, Madeline (James Short) Emery, and Jonas Marquardt.

Visitation for Mr. London will be at 10:30 a.m., Thursday, March 6, followed by the funeral service at 11 a.m., at Congregation B'nai Amoona, 324 South Mason Rd.. Interment will be in Beth Hamedrosh Hagodol Cemetery.

Mr. London loved dogs. Contributions would be appreciated to Stray Rescue, 2320 Pine Street, St. Louis, Mo. 63103, www.strayrescue.org.