St. Louis attorney Frankie Muse Freeman helped to set the tone Wednesday when she summed up what it meant to be a young civil rights activist during the '60s.

“We were all branded troublemakers,” she said, “and I’m proud of that.”

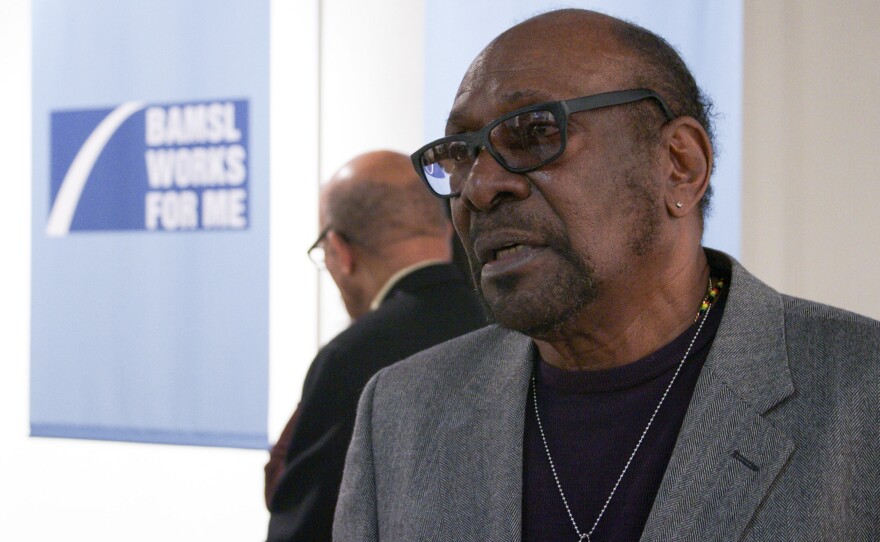

She was one of three rights leaders that the Bar Association of Metropolitan St. Louis brought together to mark the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and to talk about their work in promoting equality in St. Louis. In addition to Freeman, the panelists were Norman Seay and Percy Green. Weather conditions in the Washington, D.C., area prevented a fourth panelist, former U.S. Rep. William L. Clay, from flying here to take part in the event.

Jefferson Bank protests

In any case, the gathering was a rare one of leaders who came of age during the national civil rights movement and were either witnesses or participants in the Jefferson Bank demonstrations, the most significant rights activity in St. Louis at the time.

Beginning the year before the Civil Rights Act became law, the local protests were triggered by Jefferson Bank’s refusal to hire blacks as tellers. Eventually the bank backed down and quietly began putting some African-Americans tellers behind its counters.

Former news anchor Julius Hunter, who moderated the panel discussion, praised the activists, saying they “made civil rights happen in St. Louis. Their acts were brave, resolute, defiant, inspirational. It is on their shoulders that we enjoy freedoms that were not ours before, 50 years ago.”

Cost of convictions

All three panelists reported paying heavily for their convictions. Seay spent 90 days behind bars and was fined $500 for refusing to follow a judge’s order against protest activities at Jefferson Bank. Clay was sentenced to 270 days was fined $1,000 for his role in the protest.

The first words out of Seay's mouth during the panel discussion were, "I am old," prompting laughter from the audience. He has suffered two strokes in recent years, but talked about the time he possessed the stamina to engage in civil rights activities.

Green and Freeman both lost their jobs for activities growing directly or indirectly from Green’s employment discrimination case against the old McDonnell Douglas Corp. He said his dismissal by the aircraft company stemmed from his social protest activities. His suit became an important part of civil rights case law, because it lowered the bar of proof a plaintiff needed to establish discrimination. Green said the Civil Rights Act of 1964 helped make it possible for the court to consider job-bias cases like his own.

Freeman’s link to this issue stemmed from her work at the time as a member of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission, which held a hearing in St. Louis County on affirmative action plans of government contractors. McDonnell Douglas turned out to have an inadequate affirmative action plan, which prompted the federal government to put a hold on its federal contracting activities.

The St. Louis Globe Democrat wrote an editorial criticizing the government's action. Freeman responded by writing a letter to the editor, taking issue with points in the editorial. The day that her letter appeared, Freeman was notified that she was being fired as general counsel for the St. Louis Housing Authority.

She returned to private practice and, over the years, has been honored with numerous awards, including the American Bar Association Spirit of Excellence award.

When asked during the event about strides that black people in St. Louis have made over the years, Seay mentioned some of the prominent African-American lawyers in the audience. They included Ronnie White, formerly chief justice of the state Supreme Court; Judge Anna T. Quigless, of the Missouri Court of Appeals of the Eastern District; Anne Marie Clarke, St. Louis Family Court commissioner and former head of the St. Louis Board of Police Commissioners; and Mavis Thompson, city license collector, and former president of the National Bar Association.

To contrast progress black people have made since the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Hunter depicted St. Louis 50 years ago as a place where "Jim Crow existed every day of every year since the founding of the city. You hear and see everywhere that the city is celebrating its 250th anniversary."

But Hunter said, "The city was a comfortable nest for Jim Crow for its first 200 years."

Read more

Jefferson Bank movement turns 50; protesters from far and near recall segregated St. Louis

Race: Where are we, 50 years after the March on Washington?

Norman Seay looks back on Jefferson Bank and local struggle for civil rights

Jefferson Bank demonstrations: a civil disobedience movement like no other in St. Louis area