Jaquin Holmes has had his share of frustration with the way municipal courts in St. Louis County operate. During a meeting of the Ferguson Commission last year, the St. Louis resident talked about being treated harshly for what deemed to be minor traffic offenses.

Holmes said he’s encountered a broken system. And he wanted the Missouri General Assembly to step up.

“It’s gone out of control," Holmes said. "We really need to get to an overhaul and update ourselves to what is appropriate.”

Some lawmakers believe the Missouri General Assembly answered the call from people like Holmes by passing a sweeping overhaul of the state’s municipal court system. It’s arguably the most significant piece of legislation to pass that was inspired by the unrest in Ferguson; several other proposals didn’t make it across the finish line.

Sen. Eric Schmitt, a Glendale Republican who sponsored the legislation, contends his bill could alleviate long-standing tensions between law enforcement and residents. He also said the final product shows the legislature can seriously tackle a major issue effectively.

“This is something that will get at the root cause, I think, of the breakdown in trust between people and their government and people and their courts – which is this ever-increasing desire by many municipalities to reach into people’s pockets with traffic tickets and fines,” Schmitt said.

But while Schmitt’s bill passed with overwhelming margins and will likely receive Gov. Jay Nixon’s approval, some detractors question whether it will meet constitutional scrutiny. Others say that the measure won’t actually impact Ferguson that much and will instead hurt St. Louis County cities with predominantly black populations and elected leadership.

“If we just look at the race of people in the towns it affects more, I think we can certainly make a case for discrimination just based on who was carved out of this,” said state Rep. Deb Lavender, D-Kirkwood.

_

Turn on the bright lights

After Michael Brown was shot and killed, a number of prominent national media outlets spotlighted deficiencies in St. Louis County’s municipal court system. And while the courts didn’t necessarily have a direct connection to what happened between Brown and former Ferguson Police officer Darren Wilson, many felt that excessive ticketing engendered resentment within predominantly black communities.

Schmitt’s bill started out relatively simply, with its main provision lowering the percentage of traffic fine revenue a city can incorporate into its budget to 10 percent from 30 percent. The final bill’s threshold is 12.5 percent for St. Louis County cities and 20 percent for the rest of the state, a compromise that was probably spurred on when some rural lawmakers objected to the original bill.

But the bill also contains provisions that may end up being more impactful than the revenue cap. Those include:

- Minimum standards for St. Louis County on budgeting, administration and policing, including a requirement for county cities to have an accredited police department patrolling the streets within six years. If a city ultimately fails to adhere to these standards, it could face disincorporation elections.

- A $300 limit on municipal traffic fines.

- An automatic disincorporation election for cities that don’t remit excess revenue from traffic fines to county schools within a certain amount of time.

- Prohibiting confinement for most traffic offenses or for failing to pay a fine.

- A revamped definition of a city’s “revenue,” which had been a common complaint about the old version of the law. In laymen’s terms, Schmitt described the new definition “as basically any money that the city has the ability to spend. ... So it’s not dedicated resources or like pass-through money that goes to a particular fund — like the brain injury fund — that they don’t get to keep,” he added.

“I grew up in north county. My grandfather actually lived in Ferguson. I’m very familiar with the area,” Schmitt said. “And I wanted to make sure that we got a bill passed that provided the maximum level of reform. And so St. Louis County has a lower percentage. But I think if you look at particularly the journalism and the investigation and all the facts that have come to light, there are significant problems in St. Louis County in the municipal courts.”

Schmitt’s bill stands out because bills revamping the state’s use of force statutes, bolstering body cameras and implementing sensitivity training didn’t it make it to Gov. Jay Nixon’s desk.

Sen. Maria Chappelle-Nadal represents Ferguson in the Missouri Senate and voted for Schmitt’s bill. While she expressed frustration that other “Ferguson-related” priorities didn’t make it, due to either disagreements or legislative bickering, she adds Schmitt’s bill could make a difference — especially since it does away with “failure to appear in court” charges for minor traffic offenses.

“And that’s why I don’t understand why some of the people who are in North County didn’t recognize that there’s some great things that are in the bill,” Chappelle-Nadal said. “You’re not going to get a bill with 100 percent of what you want. We’re making sausage here in this bill.”

Unequal treatment?

What Chappelle-Nadal may be alluding to is how some of the bill’s biggest critics hail from north St. Louis County.

Some — like state Rep. Clem Smith, D-Velda Village Hills — agree that municipal courts needed big changes. But he didn’t like how the revenue cap is different for St. Louis County or how the municipal standards only apply to that county. A few lawmakers, such as Lavender, feel that the dual cap may be struck down if municipalities file a lawsuit when the bill is signed.

“It was something that was going to impact communities that not have a ‘Ferguson’ situation going down,” said Smith, referring to Schmitt’s bill. “There are some reforms in the bill that I actually do like. But there should be equally treatment — both 20 percent across the board. But this is a poor excuse. If one would want to use this as an excuse to say it’s something we did in Ferguson, it was not.”

Effect on Ferguson

Indeed, one of the ironies of the bill is that even though it was ostensibly inspired by the protests and riots in Ferguson, it won’t actually affect the city of Ferguson that much. That’s because city officials estimate that fines and court costs encompass around 15 percent of its total revenue, which is just a couple ticks above the revised 12.5 percent cap.

“The narratives that national media and others have made about the city of Ferguson ... really don’t match up with the city of Ferguson,” said Ferguson Mayor James Knowles III. “But they do match issues in the greater St. Louis area. I think Ferguson has become a symbol. Anytime I read anymore, whether or not it ‘affects Ferguson,’ I just take it as they mean the symbol and not the city.”

Knowles said his city should be able to meet the bill’s municipal standards. But he did add that the accreditation process for the city’s police department came to an abrupt halt after Brown’s death last August. (Ferguson’s Police Department, of course, was the subject of a damning Justice Department report that was released earlier this year. And that may complicate accreditation efforts, though Knowles says he hopes to resume that process soon.)

“It’s not going to affect the city of Ferguson,” Knowles said. “I think it will affect how communities organize and run their police departments and what the focus of the officers is on the street. … We have focused on community-oriented policing in the past. We are re-doubling our efforts to show those efforts really do create that citizen-engagement benefit.”

Poorer cities hit

The cities that could be most affected by the new cap are predominantly African-American municipalities in north St. Louis County. That includes such towns as Northwoods, a bedroom community where fines comprise about 25 percent of the city’s total budget.

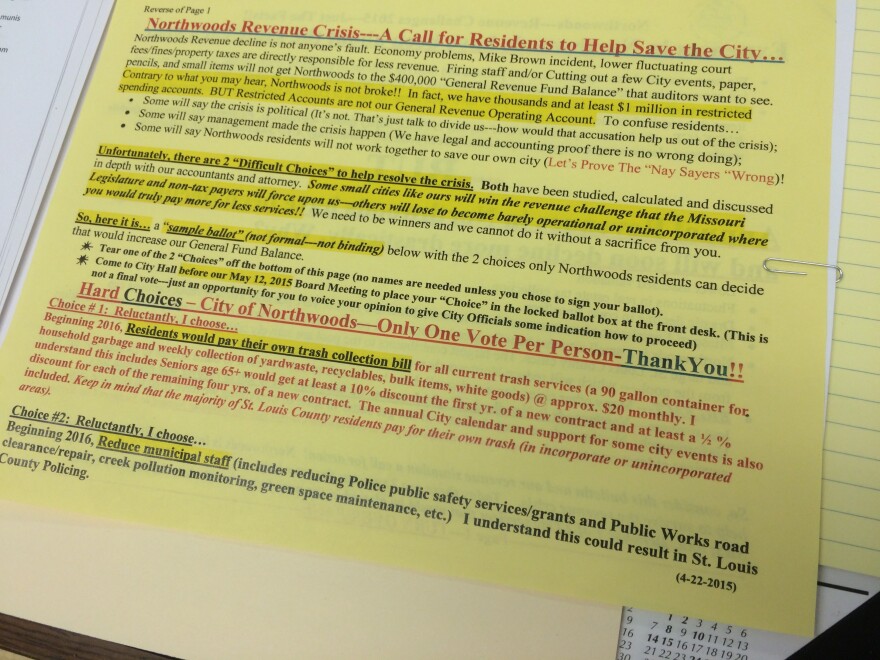

The city recently sent out fliers to residents that openly discussed taking away free trash service or cutting staff, which Northwoods Mayor Everett Thomas was linked to the passage of Schmitt’s bill. (Northwoods also received less-than-flattering coverage for holding up driver's licenses for failing to show a city car sticker — which the city isn't authorized to do.)

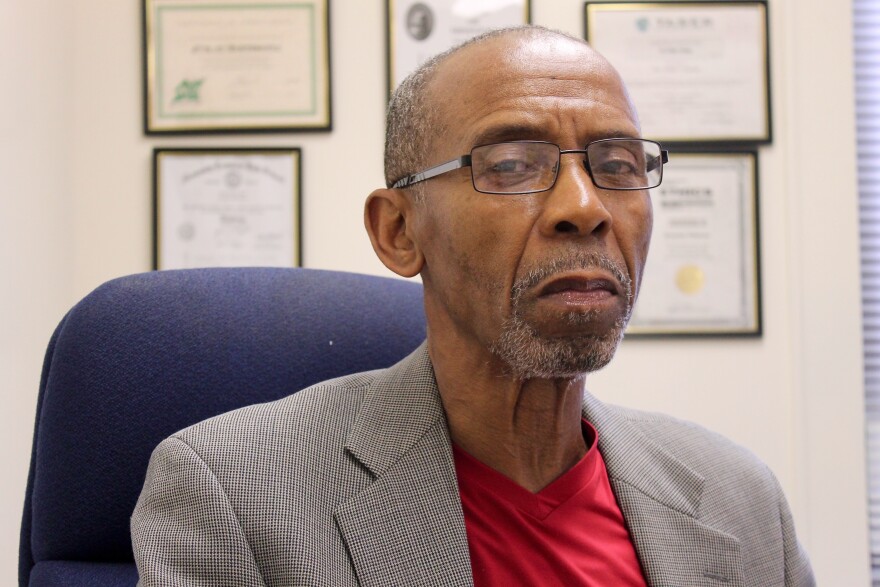

While Thomas contends his city could survive the lower cap, he’s not sure other cities that have black elected officials will be as lucky.

“It don’t look too good as this point,” said Thomas, referring to the survival of nearby St. Louis County cities. “I think a lot of the cities have already been hurting financially. This just adds to the problem.”

St. Louis University law professor Brendan Roediger was involved in the haggling over Schmitt’s bill and likes a lot of the provisions. But he emphasized “that the elimination of black power basis actually is of concern to me.

“To extent that’s the objective of some people, it’s certainly not my objective,” Roediger added.

He also questioned whether percentage of revenue was a good measurement of a city’s oppressiveness. For instance, he noted that Richmond Heights and Berkeley are about the same size and receive about the same amount of fine revenue. But he said Berkeley has a higher percentage because it’s considered a less wealthy city than Richmond Heights. “It does not make Richmond Heights’ court any better,” he said.

“I have said all along that there are municipalities in West County that are just as bad as municipalities in North County – and that using percentage of revenue to measure courts is an absurd measurement,” Roediger said. “What it really tells you is that a municipality’s poor.”

Still, Roediger doesn’t believe that the different cap threshold will fall in the courts. As to whether it makes sense, he went onto say that “certainly St. Louis County is the primary perpetrator.”

“The data shows us that St. Louis County is the worst,” Roediger said. “If courts operate the way that they are supposed to operate, they will not make money. That’s just the nature of the justice business. It should not be profitable. So I don’t think 12.5 percent or 8 percent should be the objective. I think the objective should be to have courts that do justice.”

'For the taxpayer'

For her part, Chappelle-Nadal contends that many of her municipalities will not face hardship because of Schmitt’s bill. She said she told Schmitt that the “the bill’s not going anywhere if we do not redefine what revenue is.’”

“After we redefined that section of the bill, my mayors went back and they did an analysis of what their revenue would look like,” said Chappelle-Nadal, who represents several dozen municipalities in north St. Louis County. “And many of them came back to me and said that they think they could be in line with the policy. Now, there are a few that are out there whose revenue was over 20 percent. They’re complaining. But the majority of the mayors that I have met with on a quarterly basis, they said as long as the definition changes for revenue, they can live within all of that.”

(The Post-Dispatch also reported earlier this month about how the bill doesn't incorporate non-traffic ordinance violations into the percentage cap. That may have an impact on how county municipalities may react to Schmitt's legislation if the measure is signed into law).

Schmitt too has talked with North County mayors and understands their concerns. He contends his bill is not about making cities happy — but rather helping people who feel that they haven’t been treated fairly. That, he said, includes “the predominantly African-American poor defendant that’s found themselves ensnared in the system where they’re trying to do the right thing.

“And I think nationally people are looking at this and saying ‘what is going on there?’ I think we owed it to ourselves to address that,” Schmitt said. “So I always viewed it as ‘this is for the taxpayer.’ Because I think we’re going to end up with a better structure of government in St. Louis County in particular.”