Jill Gronewald was two weeks away from starting her new job as a Ferguson police officer when Darren Wilson, a now-former member of that same department, fatally shot 18-year-old Michael Brown.

But even the protests, arson, violence, looting, and shootings that followed didn't sway her from joining the department on August 24, 2014.

"It was definitely something I had to sit down and prepare for, but I was ready. To come in here and see what I saw in the media in real life, it was surreal," she said. "Of course, I get the question, 'Why? Are you nuts coming here to Ferguson when all of this is going on?' I'm like, 'No, I'm not nuts. This doesn’t bother me.' At the time the idea of violence, the threat of violence, I knew that taking on this job."

Seeing the real Ferguson

Ever since she was a child playing with her favorite toy gun and holster, Gronewald had wanted to be a police officer. In some ways, her dream came out of nowhere. No one in her family worked in law enforcement; her parents had expected her to go to college.

But Gronewald said from day one, she wanted to help others and see "people at their worst and then go to their best." So after college and the police academy, she got a job with the O'Fallon Police Department. She was only 21 years old.

Fourteen years later, she got the opportunity to join Ferguson's force. The pay wasn't as good, but working for such a tight-knit community made it an easy choice.

"It's the community. Absolutely, I love it," she said. "It's the neatest thing to see...You see people out walking all the time. They've got the corner gardens just throughout the city. Everybody's out waving. Everybody's out talking."

But Gronewald said in the unrest following Brown's death, the media didn't portray the positive aspects she loved about Ferguson.

"When I came here and I got to see the real Ferguson and how this city adjusted to what was actually occurring, it made me want to stay here that much more," she said. "Ferguson’s community is not burning, Ferguson's community is not sitting there in rubbles. The community itself, the people that make up this community are on South Florissant cleaning it up."

Important conversations

Gronewald declined to discuss why she thinks people were protesting against the Ferguson police department and law enforcement in general, or about the Department of Justice report that found the Ferguson police and municipal courts had engaged in a pattern and practice of unconstitutional racial discrimination.

Still, Gronewald acknowledges that important, worthwhile conversations have happened as a result of "a moment of tragedy."

"Are there conversations that I’ve had, are there topics that have been discussed? Yes. Are some of them difficult to hear? Yes. Are they difficult from a police officer's standpoint? Absolutely. It's hard to wake up every day and be the focus of negative attention. That's hard because that's not us...No more is the Ferguson community a bunch of rogue cops and criminals...This community is amazing."

Despite criticisms, Gronewald said she's received a lot of support. Her name was even given to St. Louis Public Radio by a Ferguson resident as an example of an officer well known in the community.

"I have been thanked more in the last...close to 11 months that I've been here for being a police officer and thanks for the job I do than I have in 15 years that I've been doing this job," she said. "That should tell you, I mean, there's so much more than what people saw on TV. This community is not the shootings, the looting, the violence that you see on the news."

While Gronewald loves the community, she doesn’t live in Ferguson – for the same reasons she didn’t live in O’Fallon when serving on that city’s force. She said that's common among police officers.

"You work in those communities, and then everybody starts to know who you are," she said. "They start to know what you do. They treat you different...You're going to the grocery store. 'Am I going to run into somebody that I'd arrested?' It's not a very secure feeling to have that and to have children around that."

Facing threats

Worries about security have grown over the last year. Gronewald experienced anger at police firsthand while working the protest lines, where insults, rocks and bottles sometimes flew officers' way. She said she's received death and rape threats against her family - even her young daughter.

"Look at what just happened in St. Louis - an officer was ambushed...We were threatened with that numerous times out here on the street. You get people telling us, 'You're going to get yours. You got one of ours, you're going to get one of yours,'" she said. "Day in and day out, our lives here were driving into work wondering if somebody who has this vile hatred of police and the uniform are going to see inside your car...Are they going to try to do something to us?"

But even in her daily job, she said she is concerned whether she'll make it home.

"It’s not necessarily the call that we're going into that's scary, it’s the flash before our eyes of what we could lose that’s scary to us. That's the white elephant that officers talk about,” she said.

Gronewald, who said she’s written both of her children letters stored in a safe deposit box in case of the unthinkable, said anti-police sentiment has changed how she approaches the job over the last year.

“When you go to a call and the hairs on the back of your neck stand up, or you've got a car pulled over and something doesn't seem right, or you get a call for a vehicle stalled on the road, like I’ve had before, and I'm fighting a guy for a gun," she said. "I’m going to do my job, this is what I've trained to do, and this is what I love to do, and I'm going to handle that call and I'm going to come out of it alive. But the fear of it is everything I could lose if I don't."

Lighting a fire for community policing

Even with these concerns, Gronewald said “a tragedy like this has just lit a fire so much more to go out and bring the community together more.” That’s where she’s relied on a tool she’s used throughout her career: community policing.

“Our job isn't out here to write tickets and just handle calls," she said. "I get so much satisfaction out of this job by driving down a street and knowing that possibly I prevented a crime just by the officer presence there - that's one aspect of the community policing. But it's getting out and knowing the faces of the people that we serve, and it's going out and talking to the business owners, stopping on the street and having Kool-Aid with some kid, you know, that's selling the Kool-Aid."

Gronewald said since she only started a year ago, she can't speak to whether Ferguson police used the community policing model in the past. But she said longtime Ferguson officers have told her that they have done community policing for years.

For her, this policing style is a key tool to changing perceptions: “We’re the most needed yet the most hated.”

"It's the part of the community policing where you get back out and you start talking to people so they can understand, 'Hey, this is what I do every day and this is what I can do to help you every day,' and so you're going to rebuild that trust slowly for people who may not have it and you're going to further build that trust for people who are already there,” she said.

That trust is especially necessary for police to be able to deal with some of the more serious crimes Gronewald’s been called to over the last year, like robberies and shootings, she said. Gronewald said she's encountered too many residents afraid to call the police or give them information because of fear of retribution from criminals.

"Part of community policing is actively getting into these subdivisions, actively go out and speak to the neighbors, get their comfort with us, get them to understand we are here for them. We are not here to write them a stop sign tickets," she said.

Two-way street of trust

But Gronewald said she believes “it’s going to take a lot on both ends” to rebuild that trust.

"It takes the interaction with us without the expectation that something will go wrong,” she said. “Same thing on our side, it takes our interaction with everyone with the expectation that it's not always going to go downhill...I don't expect everything to go downhill, I prepare for it for when it does."

She said community members should expect professionalism from local officers.

"I want them to expect that I am going to talk to them like a human being," she said, "And I'm going to talk to them like I would talk to anyone, and when I say talk to them, talking to everyone. I don't break it down by race, I break it down by people. I don't go to a call or go to a traffic stop and break it down that way. I don't look at it that way. I have a racial profiling form that does that for me, but I don't."

Police also need to see the “big picture” when using their discretion, Gronewald said. She presents this example: A burglary is in progress at a vacant house, but police get little other information. It could be anything from a squatter, a drug exchange, someone stashing stolen property. Instead, Gronewald and her partner find five kids under the age of 11 playing hide-and-seek.

While Gronewald said the "kind of comical" situation made her "feel bad for these little guys," she still sat them down for a serious talk. She said she explained to them that technically their game of hide-and-seek was a burglary, and that they could have stumbled into a dangerous situation like witnessing a drug exchange or a rape.

In the end, Gronewald took them home, talked to their parents, and didn't charge them with a crime. Several parents thanked her.

"Was it a crime? Yeah, sure, but is that the big picture? No. The big picture is to get these kids to understand, you know, what they are doing when they make a decision like that," she said. "That’s an example of a discretion that we are able to use. Now, my reason of doing that? It's the big picture. It’s helping these kids in that instance there of understanding, not charging them with a crime. That wouldn't have got anywhere. It would have made no sense."

But she said people who are critical of the police need to change their beliefs as well.

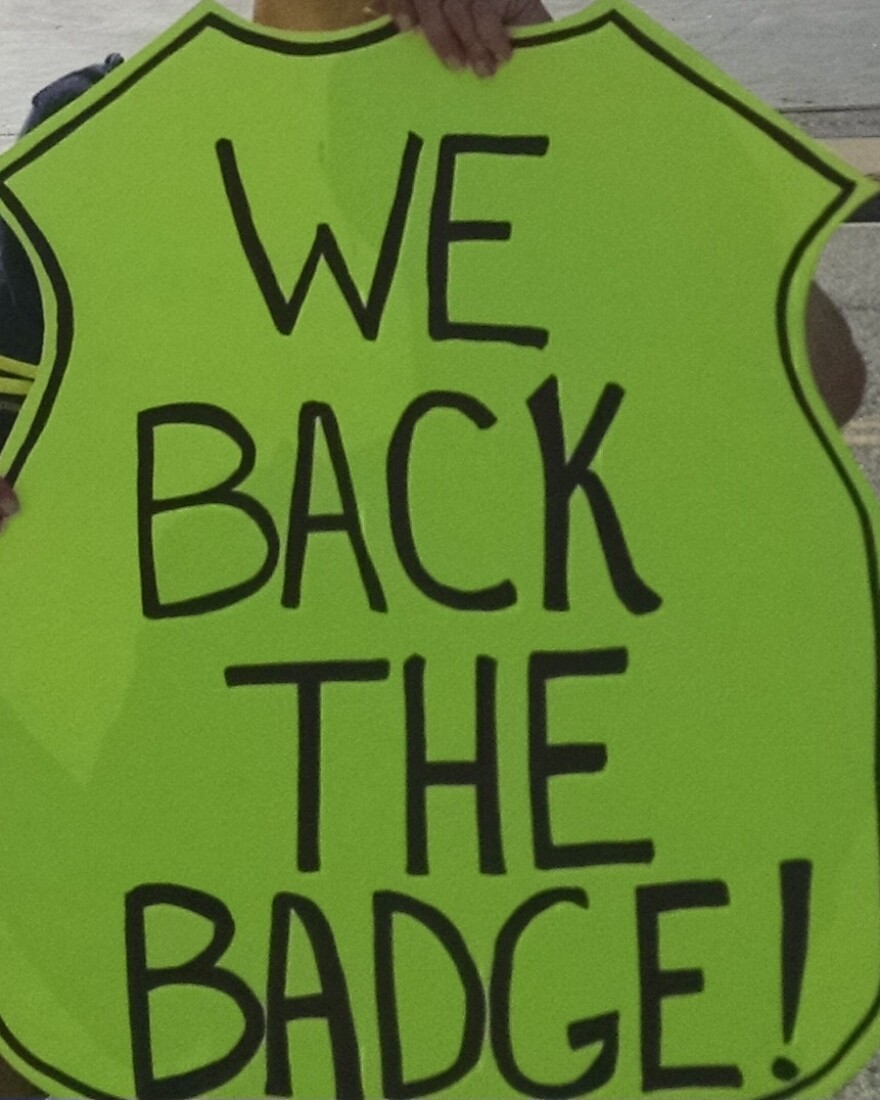

"You can expect whether you tell me you hate me (or) whether you tell me, 'Hey, I'm there for you,' I will and these officers will defend you. We're there to protect you. It doesn't matter if you say, 'FTP' and then you get hit by a car, I'm going to be there to pick your butt up. I will, I will be there to help you every stretch of the way...I want the expectation of what they expect when they see the badge, when they see the uniform, to change. I want them to expect us to help them because that's why we're here."

To get to that point, though, Gronewald said will take getting to know one another on a personal level, the ultimate goal of community policing. Reflecting on the last year, she recalls a protester with whom she'd had a productive conversation with while working the protest line. A few months after their initial conversation, the woman defended Gronewald against a newcomer to the protests who was verbally attacking her.

"She's on the same side that is blasting us, but she defended me," Gronewald said. "She said, 'No, she's nice' and she shut him down and he left me alone," she said. "It's the small conversations. It's the 'Look at me, talk to me, don't talk to the badge'... When you start opening their eyes that, you know, this badge doesn't define what you think I am - I can tell you who I am - and you start opening those doors. And it really does open a lot more conversations, and it allowed for me to be defended by people that were, their purpose at that time from what I heard of them, I don't know what their purpose was, but what I heard was 'FTP.' But it gave her an opportunity and gave me an opportunity to kind of see each other."