Every month, a million passengers come through the St. Louis airport named for Albert Bond Lambert. Most have no clue who Lambert was — and that includes people from St. Louis.

According to a survey conducted for the airport a year ago, only 17 of 600 respondents correctly identified the connection between Lambert and the airport.

St. Louis aviation buffs like Mark Nankivil are hoping to change that. He belongs to the Missouri Aviation Historical Society, which has been working to promote the history of the airport that Lambert founded in 1920.

“Lambert deserves to be known for what he’s done even though today’s generation doesn’t necessarily know who he is. A little bit of research, a little bit of history you get a sense that without him we wouldn’t have an airport there today,’’ said Nankivil, who’s also the president of the Greater St. Louis Air and Space Museum.

The historical society assisted author Daniel Rust with research for The Aerial Crossroads of America: St. Louis’s Lambert Airport, an extensive history of the airport recently published by the Missouri History Museum Press.

In conjunction with the book’s release, a timeline of historical St. Louis aviation photos are on display at the airport in The Lambert Gallery, which is located in the baggage claim area of Terminal 1.

How much do you know about A.B. Lambert and the history of his airport, which will celebrate its centennial in 2020?

Here are 5 things to know, culled from The Aerial Crossroads of America:

1. Who was Albert Bond Lambert?

Rust opens his history of the airport with an anecdote about Lambert’s vision:

It was the summer of 1920, when the pharmaceutical tycoon climbed onto a stack of hay to get a good look at a farmer’s field located about 11 miles northwest of downtown St. Louis. From that vantage point, Lambert could see more than cropland. He saw the future: an aerial transportation center serving aircraft of all sizes and types, ferrying passengers and cargo from “north, east, south and west.”

This was the dawn of the Golden Age of Aviation, the period between World War I and World War II when aviation would evolve from rickety aeroplanes to mighty aircraft made of steel.

Lambert, an accomplished balloonist, was fascinated by all manner of flying machines. Not only was he St. Louis’s No. 1 aviation enthusiast, he was also enthusiastic about the city, Rust said. If there was something going on in the city related to aviation, Lambert was probably involved.

He was a member of the Aero Club that brought balloon and air races to St. Louis in the years following the 1904 World’s Fair. In 1910, Lambert took a ride on a plane piloted by Orville Wright — and then took flight lessons from Wright’s company. In 1911, he became the first licensed airplane pilot in the city.

Lambert and the Aero Club built the city’s first permanent flying field in 1910 at Kinloch Park, a closed racetrack. That field was just northeast of the site where, a decade later, he would establish Lambert airport. (The Kinloch field hosted the International Aeronautic Tournament in 1910, which is notable for another famous first: Former President Theodore Roosevelt took a three-minute flight in a Wright plane piloted by Arch Hoxsey, becoming the first U.S. president to fly.)

According to aviation historians, the Kinloch airfield was temporarily renamed Lambert Field during the tournament. That has led to a popular — and enduring —misconception that the Kinloch airfield became Lambert airport.

During World War I, Lambert was commissioned by the Army’s Signal Corps to train balloon pilots. He earned the rank of major and served on the commission that selected the site for an Army flying field near Belleville. It’s now Scott Air Force Base.

After the war, Lambert resumed his push to make St. Louis a center of aviation — which led him to that farm field in Bridgeton in 1920, where he and the Missouri Aeronautical Society leased 170 acres for an airport. Five years later, when the lease ran out, Lambert bought the property.

Lambert had selected a site with plenty of growing room. At the time, the city had a small airfield in Forest Park that had been established for air mail flights, but it was congested and full of obstacles: trees, power lines and telephone lines.

“He selected the property, leased the property, built a hangar, graded it, opened it to the public. He said, 'If you have an airplane, and you want to fly, come on over and use this facility.' And then in 1928 he would sell it to the city for his cost,’’ Rust said.

Lambert saw the future of aviation and was determined to take St. Louis along for the ride.

“Lambert, in 1923, when he got the air races to come to St. Louis, said, ‘We have to be at the forefront of this technology. With the railroads, we’re behind the game. Chicago beat us out. We really need to have a world-class airport here because this is the technology of the future,’ '' Rust said.

After selling the airport, Lambert remained active in civic affairs. He served on the city’s airport commission, the board of aldermen and the police commission.

2. The airport that Listerine built

Lambert was born in St. Louis in 1875. His father, Jordan Lambert, founded and owned the Lambert Pharmaceutical Company, which marketed an antiseptic mouthwash, still sold today: Listerine.

He was just 21 when he left college — the University of Virginia — to become president of his family’s company. Under his leadership, the company expanded internationally.

“He would go to Paris and to Hamburg, Germany, to set up factories, and while he was there, he would meet up with aviation enthusiasts of the day,” Rust said.

Lambert also enjoyed motorcycles and golf. He was on the U.S. golf team that competed in the Summer Olympics in Paris in 1900 and the 1904 Summer Olympics in St. Louis, where the team won a silver medal.

In 1920, the same year Lambert founded his airfield, his company’s marketers renamed bad breath “halitosis” — and Listerine sales rose like a hot-air balloon.

“Thanks to Listerine, he had lots of money and spent much of it on aviation,’’ Rust said.

3. Lambert backed Charles Lindbergh

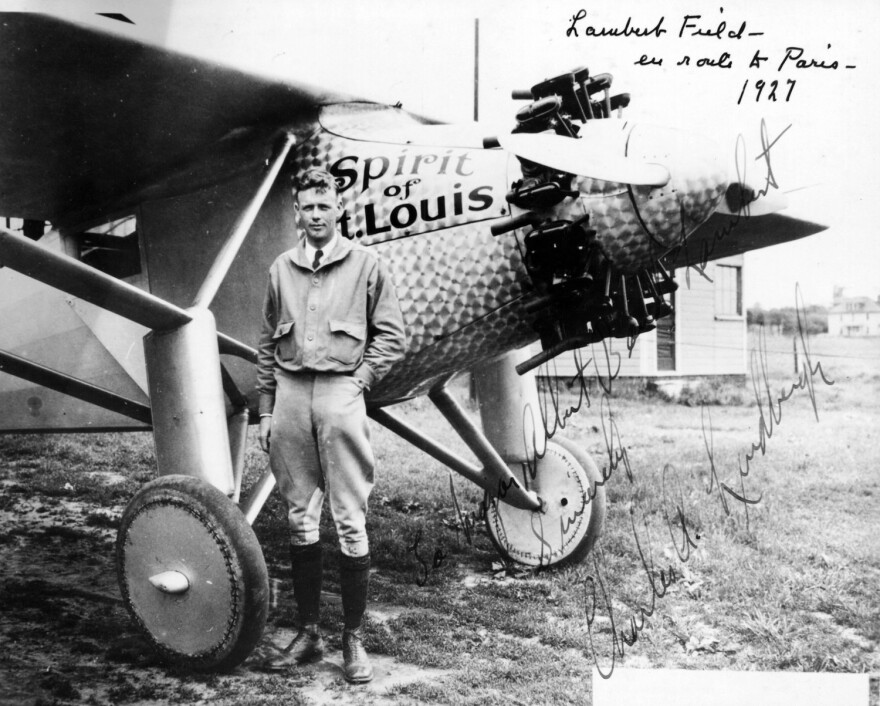

Charles Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis have always gotten the city’s aviation glory, but Lambert was the mover and shaker who got things done.

Rust writes that it was Lambert’s support of Lindbergh that paved the way for the young pilot to get the financial backing he needed from prominent St. Louis businessmen to make his epic transatlantic flight in 1927.

Lindbergh was a barnstormer who first came to Lambert’s airfield in 1923 for the air races. He would stay on in St. Louis, working as a flight instructor. He then became an airmail pilot for the Robertson Aircraft Corporation, which had landed the contract to deliver airmail between Chicago and St. Louis.

When Lindbergh decided to take a shot at winning the Orteig Prize —$25,000 for the first nonstop flight between New York and Paris — he took his plan to Lambert.

“Really, there would have been no Lindbergh without Lambert,’’ Rust said. “Albert Bond Lambert was the first to really believe in what Lindbergh wanted to do — to fly across the Atlantic, a single-engine airplane by himself. Lambert, when he heard about it, told Lindbergh, ‘I’ll put the first $1,000 toward your project.' And when others found out that A.B. Lambert believes in this kid and his audacious idea, they thought that maybe they should get on board, as well.’’

4. In 1970, Lindbergh argued for keeping Lambert in the airport's name

In January, the name Lambert-St. Louis International Airport will be flipped and officially become St. Louis Lambert International Airport. Lambert’s name will remain in the official title, but top billing will go to its geographic location, the city of St. Louis.

The change was approved by the mayor and board of aldermen in October. An airport working group had proposed that the name be changed to “St. Louis International Airport at Lambert Field,” but that didn't sit well with St. Louis aviation buffs and descendants of Lambert.

Nankivil said the fear was that, in the future, it would be too easy to lop “at Lambert Field” from the airport's name.

Airport director Rhonda Hamm-Niebruegge said that putting St. Louis first in the name will enable the airport to adopt a more cohesive and global marketing platform, while continuing to recognize Lambert's legacy.

“The name change was never about forgetting that,'' she said. "The name change was to unify this airport with the region and tie those two together.”

The aviation historians point out that Charles Lindbergh got involved in 1970 when the airport commission changed the name from Lambert-St. Louis Municipal Airport to St. Louis International Airport, dropping Lambert from the name, all together.

“People were not happy with this,’’ Rust said. “Even Lindbergh himself wrote a letter and said, “How dare you do this? This is a nameless, faceless airport title. We need Lambert’s name on it.’ So, less than a year later the airport commission voted to have it renamed as Lambert-St. Louis International Airport.’’

5. Lambert’s vision of the future has played out at his airport

Lambert lived to see his fledgling airport grow into a major municipal airport. He died in 1946,

“The airport is one of the oldest municipal airports in the nation and so much happened here. I liken it to a microcosm of aviation history,’’ Rust said. “The major themes of aviation history are all found right here: Everything from the evolution of airlines to having giant hubs — and de-hubbing. Of manufacturing aircraft. Military flying.’’

The history of TransWorld Airlines — TWA — can be traced to Lambert Field in the mid-1920s, Rust noted. His history delves into the impact of TWA’s decision to make Lambert its hub of operations in the 1970s, and the aftermath of the deregulation of the airline industry and de-hubbing by American Airlines in 2003.

Rust also traces the history of airframe manufacturing at Lambert, which began in 1928 with Robertson Aircraft and continued after World War II with McDonnell Douglas and now Boeing.

“To have that continuous production of aircraft at this location is really quite phenomenal,’’ he said.

Also phenomenal is Lambert’s Terminal 1, which was designed by Minoru Yamasaki in the mid-1950s. It replaced the airport’s outdated terminal that was constructed in 1933 and looked like a big train depot.

“Yamasaki designed this terminal to be much more in tune with the aircraft aviation age — to be a great gateway to a great city,’’ Rust said. “He designed it to have these giant arches and to be a thin-shell concrete structure that was unlike anything else in aviation. And when it was dedicated in 1956, it was a wonder. It got many awards for its architecture. It’s really a jewel for St. Louis.’’

Yamasaki would later design the World Trade Center — the Twin Towers in New York that were destroyed in the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. Yamasaki also designed another famous project for St. Louis in the early 1950s — the failed Pruitt-Igoe housing project, which was famously demolished two decades later.

Hamm-Niebruegge says it’s not uncommon for travelers to post photos of Yamasaki’s terminal design on social media.

“We’ll see somebody who takes a picture of it as they’re traveling, and they’ll say, ‘Oh, this terminal is so historic.' Or, ‘This terminal is so fabulous. I love this design and architect.’ ''

Follow Mary Delach Leonard on Twitter: @marydleonard