Andrew Theising was sitting behind the steering wheel of his car, pointing out the pathways of city streets that vanished long ago beneath a parking lot in downtown East St. Louis.

“This is where the homes were burned,’’ he said, solemnly. “This is where African-Americans were hung from the streetlights. This was the height of the violence and the bloodshed.’’

Theising, an associate professor of political science at Southern Illinois University-Edwardsville, was describing the 1917 East St. Louis race riot.

He was parked outside the East St. Louis Higher Education Campus, just off Eighth Street. A century ago, a mob of white people burned the African-American neighborhood that stood on this spot and then shot many of the victims as they fled the flames. Others were lynched from streetlights.

Officially, 39 African-Americans and 9 whites died during the violence of July 2-3, 1917, but most historians put the toll much higher.

Most people don't realize the college campus is located where some of the worst incidents occurred because the sites have never been marked, Theising said.

One of the goals of the East St. Louis Centennial Commission that’s commemorating the anniversary of the race riot is to place historical markers at more than 20 locations associated with the deadly violence a century ago. Theising, who’s a member of the commission, calls them “sacred sites.”

“People go through East St. Louis — we drive by these sites all the time. But we have no idea of the tremendous history and the pain and the suffering that happened on these places,” he said.

“East St. Louis was this place that had no rules”

Before the official anniversary events, scheduled for July 1-3, Theising will take small groups from SIUE on tours of the sites, much as he was doing for a reporter on this morning.

He began by playing music — Duke Ellington’s “East St. Louis Toodle-Oo,” recorded in 1927, 10 years after the riot.

“Doesn’t that just sound kind of sinister and sultry,’’ he said, after a few moments.

“This was Duke Ellington’s view of East St. Louis. I think it helps to understand that before the riot and after the riot, East St. Louis was this place that had no rules. Where laws were never enforced. That the riot happened in this place is not surprising.’’

As Theising drove, he told the story of the city’s industrial past: corrupt politicians who aided or ignored organized crime, factory owners who made no investment in the community; the clash between labor unions fearful of losing jobs to black workers who were migrating from the South in search of better lives.

Most of the buildings from 1917 have been gone for decades, including the labor temple at Collinsville and St. Louis avenues, where speakers incited the rioters to go home and get their guns. Theising stood at the intersection as cars and trucks rumbled by and described the start of the riot a hundred years ago.

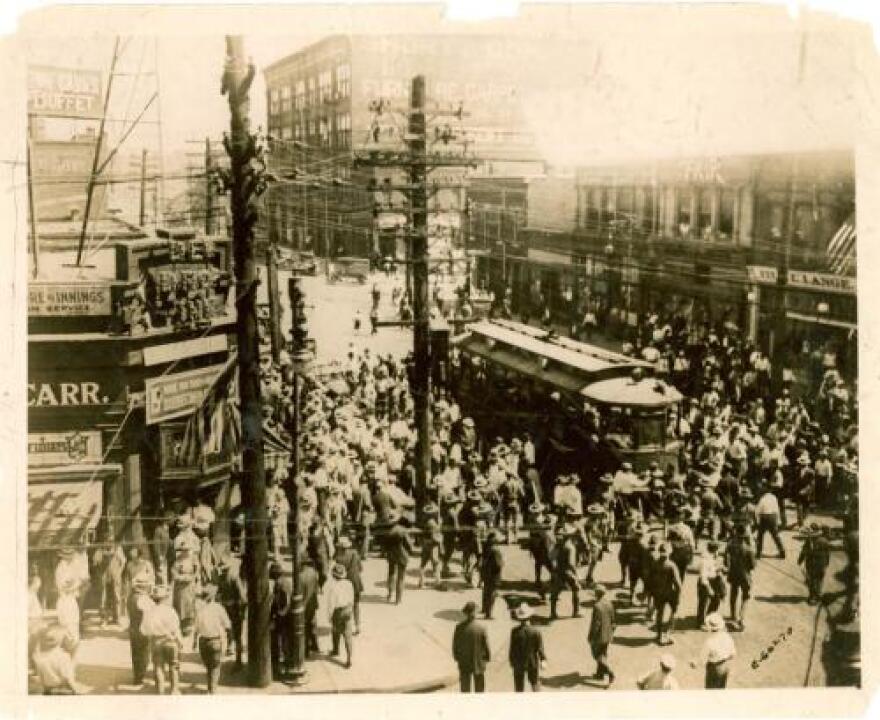

“They marched past Missouri Avenue, and then when they got to Broadway that’s when they started encountering African-Americans,’’ he said, pointing down the street. “And they randomly just started grabbing and beating people on the streets. There’s a very famous picture of a streetcar that was stopped and the African-Americans were pulled off the streetcar. That happened right down here.’’

“Lives were lived here, and lives were given here”

Theising hopes the historical markers will spur an ongoing discussion of the causes and legacy of the riot.

He is director of the Institute for Urban Research at SIUE and has researched East St. Louis for 25 years. He’s also written extensively about the city’s history and development.

Theising uses old city street maps and satellite imagery to trace the locations of the sites, which are detailed in historical accounts of the riot.

And, he weaves the harrowing testimony of victims into his narrative.

At a vacant lot at North Fourth and Division streets, he read the words of Narcis Gurley, 71, whose home was burned: “Between five and six o’clock we noticed a house nearby burning and heard the men outside. We were afraid to come outside and remained in the house, which caught fire from the other house. When the house began falling in we ran out, terribly burned, and one white man said, ‘Let those old women alone.’ We were allowed to escape. Lost everything, clothing and household goods.’’

Gurley had lived in East St. Louis for 30 years before the riot, making her living by keeping “roomers” and working as a laundress.

Theising said these stories need to be heard today.

“The worst thing we can do is ignore this place. Because lives were lived here and lives were given here and people still struggle in this community,’’ he said. “How can we ever think of fixing the problems in our cities if we don’t understand where they came from and if we don’t understand that they exist.’’

The Meridian Society, a philanthropic organization at SIU-Edwardsville, is paying for the historical markers. Theising hopes they will be in place by fall.

The centennial commission is also raising funds for permanent memorials that will be placed at the Higher Education Campus and at the base of the Eads Bridge. Hundreds fled across the bridge during the riots, seeking shelter and safety in St. Louis.

Follow Mary Delach Leonard on Twitter: @marydleonard

Help inform our coverage

If you are a descendant of someone who went through the East St. Louis race riot of 1917, or know someone who is, we invite you to share your story: What's your connection to the 1917 race riot in East St. Louis?