Most people have heard about the undesirable side effects that chemotherapy has on the body of people suffering from cancer. There's balding, fatigue and loss of appetite, to name a few.

Until recently, however, chemotherapy’s effects on the brain weren’t widely recognized. The cognitive side effects – a fuzzy memory and poor attention span – were usually dismissed by physicians, scientists and even some cancer patients.

The symptoms have a name: Post-chemotherapy cognitive impairment, or “chemobrain,” among those who suffer from it.

Many describe the phenomenon as a “mental fog” that persists even after the chemotherapy has ended. They liken it to those moments when you forget what was on your grocery list or where you put your keys. But for some patients who have received chemotherapy, these memory lapses happen all of the time.

Scientists at the Washington University School of Medicine now believe the cognitive effects of chemotherapy are not just anecdotal: Chemobrain can be seen via brain imaging.

Dr. Bradley Schlaggar, a pediatric neurologist at the school of medicine, is one of the co-investigators of the pilot study that shows evidence for chemobrain. He and some colleagues began the study with a group of 28 women who underwent chemotherapy for breast cancer. Half of the group reported signs of cognitive issues and the other half none at all.

A personal connection

Schlaggar was already interested in studying the chemobrain phenomenon when an odd thing happened. His wife, Hristina Lessov-Schlaggar, was receiving chemotherapy treatment for breast cancer in 2012 when she started experiencing chemobrain. Lessov-Schlagger is also a neuroscientist at Washington University.

'When I was first starting to feel my brain going coo-coo, we stumbled upon publications that basically said, 'Get over it. This isn't real.'

She said she can pinpoint the moment she realized something was wrong: When she struggled to re-read a scientific abstract she herself had written.

“I couldn’t understand. I couldn’t follow it,” she said. “I was getting confused as I was reading it. And an abstract is 300 to 500 words, about a half a page of single-spaced text. I remembered what I was trying to say, but I couldn’t process it.”

This mental battle was the first of many. She started forgetting to pick up her children and to buy the groceries. Schlaggar said what was happening to his wife was completely out of character. But it afforded him the opportunity to explore chemobrain in a way not many others could.

“My wife is also a scientist, and a neuroscientist,” Schlaggar said. “So – as I always do about any question I have – I asked her opinion. I asked her: What is it like? What does it feel like? Can your insights help guide the way we ask these questions?”

Although Lessov-Schlaggar was not officially a part of her husband’s study, the couple joined forces to find out what was going on. They scoured publication after publication. What they found was a lot of skepticism surrounding chemobrain.

“When I was first starting to feel my brain going cuckoo, we stumbled upon publications that basically said, ‘Get over it. This isn’t real’,” Lessov-Schlaggar said.

Schlaggar said some physicians would even go so far as to attribute the mental effects of chemotherapy to age, hormones or “adjustment disorder” – a condition in which patients receiving bad news cannot deal with a bad blow.

But, as Schlaggar's studies started to unfold, he suspected that wasn't the case.

Chemobrain up close

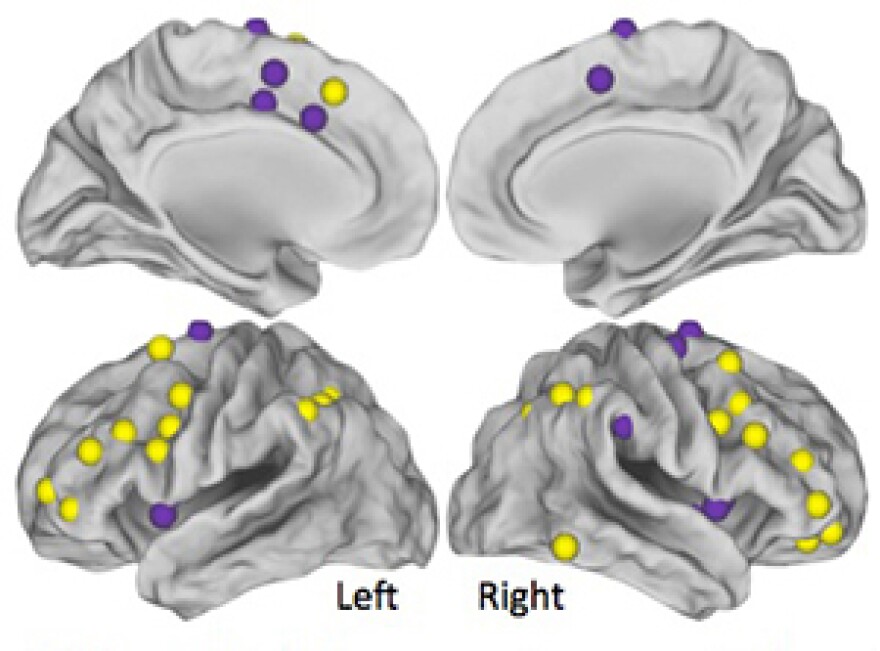

At medical centers throughout the country, labs had begun to investigate the physical evidence of chemobrain. One way of investigating it is through a positron emission tomography (PET) scan, which measures the amount of sugar consumed by the imaged tissues. Schlaggar and his colleagues took it a step further. They used a special magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, which tests the connections of the brain while the patient is resting.

“The idea was that if there’s cognitive impairment due to chemotherapy, the signature of that might show up in atypical relationships between these brain systems,” he said.

After examining MRI images of the women who reported having chemobrain, Schlaggar said the disorder leaves a clear “brain signature,” one that is markedly different from the images from women who did not have chemobrain. In this “signature,” the normal signals involved in paying attention and memory retention had gone haywire throughout the brain. Though small, he said the initial studies confirm chemobrain is real.

The validation of the chemobrain phenomenon is a milestone in and of itself. But little is yet known about its causes.

“Exactly why it happens -- and why it happens in some women and not others -- we're certainly not at the point yet,” Schlaggar said. “We’re really at the very beginning of this complex question.”

Several labs across the country are using MRIs and other imaging techniques to continue building the case for chemobrain. At Washington University, Schlaggar and his colleagues still need to conduct studies with more patients enrolled to confirm their results.

Understanding it is one thing. Treating it is something else

An even bigger issue is how to help chemobrain sufferers at the clinical end. For that, Schlaggar and his colleagues went to Timothy Wolf, an assistant professor in occupational therapy at the Washington University School of Medicine.

In the school’s occupational therapy labs, Wolf walks his chemobrain patients through a memory-training therapy called “metacognitive strategy,” which he had tweaked from his work with stroke patients. In stroke patients, Wolf said he observed many of the same cognitive symptoms chemobrain patients also report, such as memory loss and a lack of attention span.

Barbara Addelson, a St. Louisan who underwent chemotherapy for breast cancer in 2012, is one of his chemobrain patients. Addelson's goal with Wolf was to exercise more. The strategy for doing so: watch engaging television shows. Before Wolf's training, Addelson had trouble getting through even part of show.

Today, however, her challenges are different: She’s about to run out of episodes of the Netflix hit "Orange is the New Black."

“And that is so captivating, that I can go through the whole show – 50 minutes,” Addelson said. She gave Wolf an account of the length of time she could pay attention. “I even did 60 minutes on Sunday, 52 minutes on yesterday. I far exceeded 2.5 hours, and I’m really proud of myself.”

The success of the therapy isn’t limited to Addelson. Wolf said his other patients are meeting their weekly goals as well, such as exercising more or making time for friends.

“They’re reporting that they’re able to do better on activities that we never even talked about in rehab,” he said.

While clinicians continue to make progress on how to help chemobrain patients, strides have yet to be made to answer how chemobrain begins and whom it affects. Schlaggar said future studies should examine genes and other factors that run a high risk for the development of chemobrain. Knowing that, he said, will one day prevent cancer patients like Addelson or Lessov-Schlaggar from wandering in the mental fog.

Correction: The article has been updated to reflect that Addelson's goal in occupational therapy was to exercise more, not necessarily improve her ability to pay attention.