(Part 2 of 3)

Earlier this month, a new anti-heroin law went into effect in Illinois. The measure requires first responders to carry the opiate overdose antidote naloxone and expands the amount of addiction treatment paid for by Medicaid. But how the drugs and treatment will be paid for is unclear. State funding for addiction treatment is also in limbo as Illinois enters its 13th week without a budget.

Meanwhile, there have been a number of legislative attempts in recent years aimed at fighting the heroin epidemic in Missouri. But the only bill to become law is a measure allowing law enforcement to carry the overdose antidote. And so far very few police departments have taken advantage of the law.

The St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department told St. Louis Public Radio it is leaving naloxone in the hands of EMTs because ambulances arrive very quickly in the city. And earlier this year the St. Louis County Police Department said insurance complications and training requirements were delaying use. A county spokesman told St. Louis Public Radio last week the department is close to having the antidote in patrol cars.

Missouri also remains the only state in the country without a prescription drug monitoring program. The idea of the program is to help doctors and pharmacists know when someone is filling multiple prescriptions for pain pills. Opponents say creating a prescription database could violate patient privacy.

Overdose antidote bill falls short due to senate stalemate

Some legislators, advocates and law enforcement believe that putting the opiate antidote naloxone into the hands of friends and family of addicts would be more effective at saving lives than limiting access to law enforcement and medical personnel.

A House bill that would have given the public that access was one of the victims of the Senate stalemate at the end of the 2015 Missouri Legislative session.

Tiffany Addington, a Pulaski County resident, was one of the individuals pushing for the bill; called third-party Narcan (Narcan is a brand name for naloxone).

She was working alongside others with the Lime Tree Recovery Group based in Waynesville, Missouri, and advocates from throughout the state.

The Lime Tree Recovery group was founded by Addington, Gary Carmack and other concerned citizens in Pulaski County. Addington's best friend and Gary's son, James Carmack, died of a heroin overdose in 2013.

Addington said that Carmack was known as a gentle giant among their friends.

“He had like a beard in the 6th grade,” Addington said. “I remember people always thought he was older than what he really was.”

She explained that she moved around a lot when she was younger. But when she settled back down in Pulaski County she tried to contact James to reconnect, but things were just different between them.

Before long Carmack told her what was going on. He had started using prescription opiates to get high – prescription pills and painkillers, but as the pills got more expensive and harder to find he began to turn to heroin.

Addington said James began to steal from people and eventually he was put in jail. They wrote to each other during the forty days Carmack was locked up and made plans for him to get out of Pulaski County and get help.

Then Carmack asked if Addington would take him to church with her when he got out. She agreed and once he was released they made plans for Addington to pick him up on Sunday morning for church.

But that would never happened. Three days after James got out of jail he died of a heroin overdose in the bathroom of his mother’s house.

Addington still remembers the day vividly. It was Saturday, Sept 21, 2013, and she was walking out of her house when her mom called.

"I know that Narcan may not have been able to save James, but I know it could have saved countless other people."

“And then she starting crying,” Addington said. “She starting crying and she said "James died." And I just, I lost it. I started yelling at her. Just saying, "You’re lying. He’s fine. He just got out. I just talked to him." And she was saying "No. It's James." And I just fell to the floor and starting kicking and punching things. And it was just, it was awful.”

After James’ death, she and his father began to talk about what they could do to help addicts throughout Missouri and perhaps save the lives of addicts like James.

Together with the local law enforcement, a group of Pulaski County community members brought the issue of heroin and opiate abuse and overdoses to the attention of state Representative Steve Lynch.

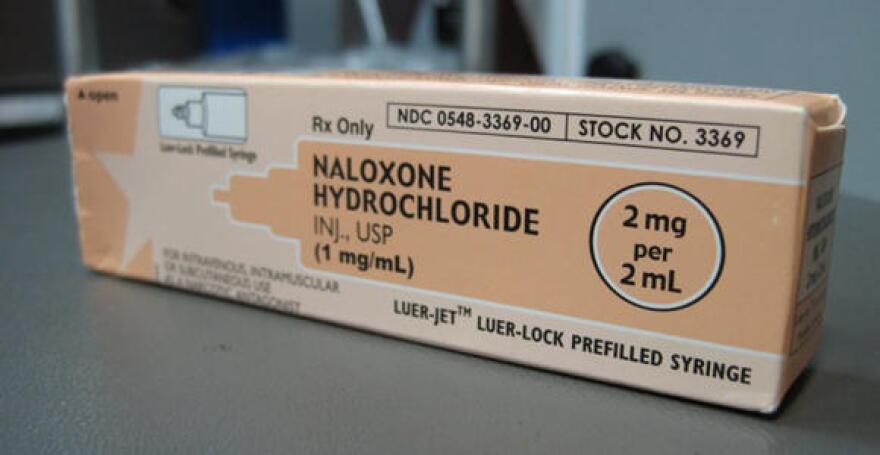

Lynch, R- Waynesville, said he is as surprised as anyone that he is working to increase access to naloxone, which reverses overdoses. It allows someone having an overdose to breathe and gives medical professionals more time to arrive.

“It's an antidote that reverses the effects of heroin immediately when it's given to an overdose victim,” Lynch said. “Snap them right out of it. It's called naloxone. It's known by its trademark name of Narcan. It works 97-99 percent of the time.”

Narcan works as an opiate antagonist, meaning it fills the opiate receptors in the brain and pushes the heroin or other opiate out. This effectively reveres an opiate overdose.

Lynch said in Pulaski County alone, in the last five years there have been 500 overdoses and 50 deaths. He considers this a “tremendous amount of death and overdoses for a rural community.”

Through talking with Addington and James’ dad, who also happens to be a childhood friend, Lynch said he came to realize how important naloxone is to protecting the lives of addicts.

House Bill 538, which Lynch proposed, would have allowed anyone to get Narcan from a pharmacy without a prescription. It would have made a nasal spray and auto-injector version available to anyone willing to purchase it.

People would still have to go to a qualified pharmacist or pharmacy technician, but there would be no additional hoops to jump through, such as acquiring a prescription from a doctor. Individuals would simply leave some basic information with the pharmacist, just like with flu shots.

Currently it is legal for EMTs and first responders to carry and administer naloxone, but Lynch said sometimes that’s not enough.

“There is only like 5 to 7 minutes to save that person, so minutes matter. So we moved Narcan from the ambulances to the first responders and now we are literally moving them to the home,” Lynch said.

"Drug addicts don't do drugs because they have Narcan available. They do drugs because they are addicted."

There weren’t many opponents to the bill. It passed the state House 146 to 1. But then it got stuck in the Senate at the end of the session, just like nearly every other bill, thanks to a general blockade. This followed the passage of Right to Work during the waning days of the session.

But there were some opponents to this bill and they were worried that by making Narcan more available, addicts would begin using drugs in higher amounts because they now have a safety net. Lynch said this is not the case.

“Drug addicts don't do drugs because they have Narcan available,” Lynch said. “They do drugs because they are addicted. They're chasing the next high.”

Lynch and Addington, along with others, stressed that addiction is a disease and needs to be regarded in much the same way as Type 2 diabetes or hypertension.

“It all boils down to do you want this person to live or do you want this person to die,” Addington said. “And that's unacceptable to say because of your life choices, because of your disease, I don’t think you deserve a chance at life. That's not fair.”

Since James’s death, Addington and others in Pulaski County have started the Lime Tree Recovery group in his honor.

They have pushed for naloxone legislation and Addington said this bill is essential for families and for protecting the lives of addicts.

“These families need this. They need this. I know that Narcan may not have been able to save James, but I know it could have saved countless other people," Addington said.

According to a representative from Lynch's office he not only intends to reintroduce the third-party Narcan bill during the next legislative session, but will be pre-filing the bill in December of this year.

This story was originally produced for KBIA as part of Side Effects Public Media.