In the first half of the 20th century, segregation touched virtually every part of American life. Black residents of St. Louis weren't just barred from schools, lunch counters and drinking fountains reserved for whites. Even hospitals could refuse to admit black patients.

But the hospitals that were built to serve African-American patients hold a special place in medical history. The facilities employed and trained thousands of black doctors and nurses. In St. Louis, Homer G. Phillips Hospital quickly became a trusted household name. Today marks the 80th anniversary of its dedication ceremony on Feb. 22, 1937.

“It was a national anchor,” said Dr. Will Ross, a nephrologist and associate dean at Washington University. “Homer G. was able to address this myth that you could not get a number of African-American physicians of high caliber and have high-quality, clinical care as a consequence.”

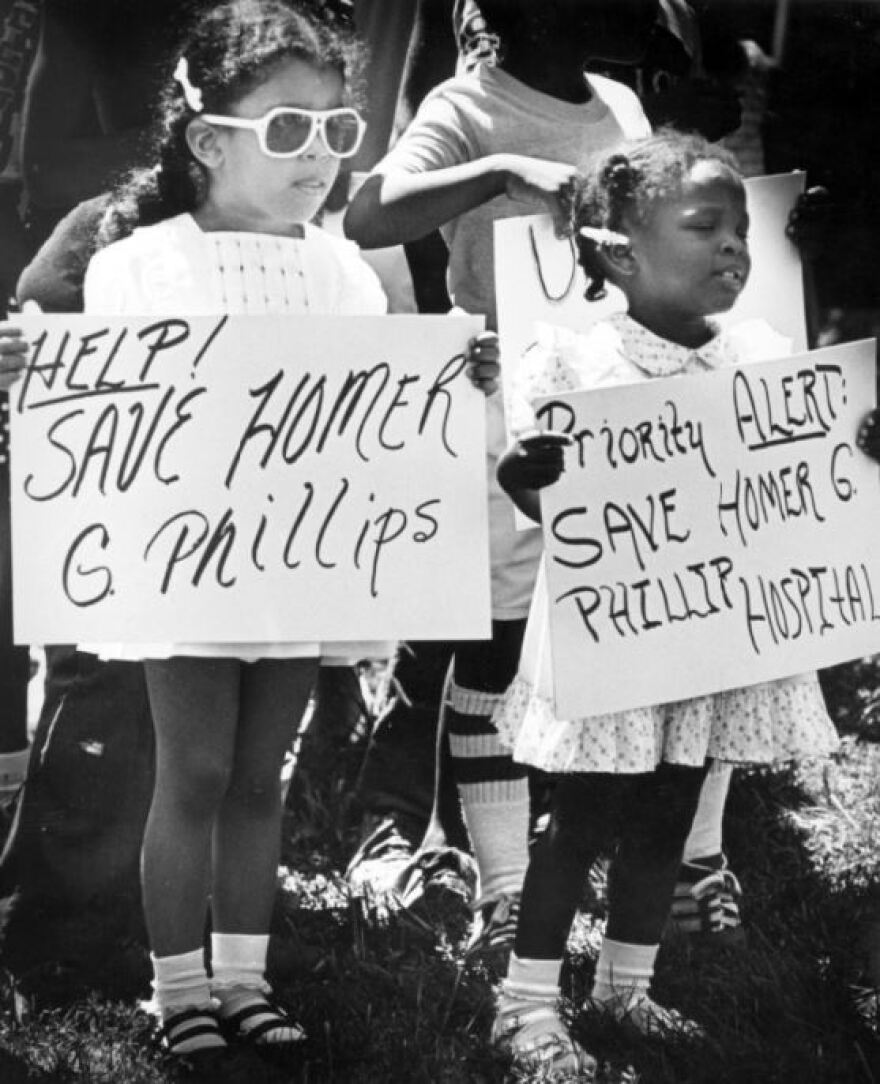

But city officials closed the hospital in 1979 — a move that sparked protests and a deep feeling of betrayal that continues to this day.

“You have to move like heck to save a life.”

The building is now a retirement community, but when Dr. Nathaniel Murdock walks through the automatic doors of what used to be Homer G. Phillips Hospital, he remembers exactly where things used to be.

“This was the emergency room,” he said, pointing past a carpeted staircase. “On the 4th floor of the hospital was OB-GYN… we had that whole corridor, from here to the end of the hospital.”

Murdock, a 79-year-old, semi-retired OB-GYN, is still recognized by his former patients. By his estimation, he delivered some 7,000 babies in the 1960s and 70s.

“We say OB is 90 percent boredom, and 10 percent sheer terror. Because you have to move like heck to save somebody — save two lives, sometimes,” he said.

Early in the 20th century, black residents in St. Louis had few options to seek medical care. Patients would be sent to segregated wings of white hospitals, or to an overcrowded facility called “City Hospital No. 2.”

After years of delay, St. Louis passed a bond issue and built a 728-bed hospital at 2601 Whittier Street in the Ville neighborhood. For 42 years, the Homer G. Phillips Hospital served African-American patients in north St. Louis. It also recruited, hired and trained black doctors and nurses from all over the country.

In the Jim Crow era of legalized discrimination, being able to see a black doctor meant so much, Ross said.

“There was a sense of comfort, knowing they were in an environment where they knew someone was going to look after them,” he said. “They were not going to be treated as second class citizens.”

Ross, who once served as the medical director a successor hospital, the St. Louis Regional Medical Center, is now co-authoring a book on Homer G. Through his research, he’s learned how the hospital did more with fewer resources than the city-run hospital for whites. The quality of surgical and obstetric outcomes was particularly impressive, he said.

“With fewer financial resources, fewer technical resources, and physical plans that were suboptimal,” Ross said. “With those constraints, the physical outcomes were just as good, if not better. That’s what’s remarkable.”

For former employees of Homer G., some of the fondest memories are of a closeness between doctors, nurses, and other staff. The hospital trained thousands of nurses in an on-site nursing school, and was one of just a few U.S. hospitals that would admit African-American doctors into residency programs.

Murdock remembers meeting with the residents in his living room to help them study for exams.

“People ask me, ‘What do you like best about your life?’ and my answer has always been this,” he said. “I loved seeing them come in as first years, and I loved seeing them pass their boards.”

“Homer G. Phillips has hero status among black hospitals in the U.S.,” said Dr. Richard Allen Williams, a cardiologist and president of the National Medical Association. “It occupies an important niche in black medical history.”

A hospital shuttered, with little warning

But the era would not last forever. In 1964, the Civil Rights Act ended segregation in the United States. Stopping discrimination in hospitals began under the Hill-Burton Act nearly 20 years earlier, but the law still allowed for patients to be held in separate wings.

In the 1970’s, St. Louis officials decided that for financial reasons, one of the municipal hospitals would have to close. City Hospital No. 1 was more ‘centrally located,’ but Homer G. had a newer building.

At the time, then-mayor James Conway told reporters that the facility was “a monument to racism, built according to the attitudes prevalent at the time. We're trying to get away from those attitudes."

Related: ‘Take me to the G’: Black St. Louisans’ struggle for access to quality health care

In August of 1979, Murdock and his coworkers were brought into a room to hear the news.

“I think most people were crying and carrying on,” he said. “Because it really served this community, and it gave a lot of people jobs.”

The switchboard had been turned off, recalls Dr. Mary Tillman, a pediatrician. She didn’t know what happened until she tried to drive into work to see her patients.

“I was met with all the police, the dogs, the horses. I was telling the police, I’m trying to go to work, what’s going on? And he drew a nightstick on me,” Tillman said.

Patients were taken from their beds and transported to other hospitals. Protests erupted. The loss still hurts for the doctors who worked here.

“That was the day that I remember, though I wish it had not happened, and I did not have to remember it,” Tillman said.

Tillman, Murdock and many of their coworkers from “the G” continued to practice in St. Louis for the rest of their careers. The building stayed vacant for a while, then was remodeled and reopened in 2003 as senior housing. City Hospital No. 1 would meet the same fate a few years later.

Williams, of the National Medical Association, also studies the history of black hospitals in America. He said the end of segregation led to financial difficulties for several hospitals like Homer G.

Chicago’s Provident Hospital, the first African-American owned and operated hospital in the country, closed in 1987 after financial difficulties. (It later reopened).

“Hospitals like Homer G. Phillips were no longer the sole hospitals that served as safety nets for blacks,” Williams said. “It led to the closure of not only Homer G., but also other predominantly black hospitals in the U.S.”

A neighborhood lost

The story of losing Homer G. is also a story about the end of segregation. Though the country ended the injustice of separating patients based on the color of their skin, the Ville neighborhood lost a major employer. When restrictive housing laws were stripped away, many families started to move.

The bustling, vibrant Ville neighborhood was once the epicenter of black life in St. Louis, said Ross. It never recovered after the loss of Homer G.

“It hurts me, when I drive through there,” Ross said. “The vacant lots, the boarded up homes, the broken windows.”

The feelings have motivated him as he and co-author Candace O’Connor completed dozens of oral history interviews over the past year. They hope to complete a manuscript by the end of next year.

When Ross closes his eyes, the memories come back.

“Children running through the streets playing games, and streetcars, and people out shopping, and doctors in their white coats running to work,” Ross said. “I can just see that image. And I go back now, and I see the injustice."

"That’s why I feel we have to tell this story.”

Follow Durrie on Twitter: @durrieB.