As Congress faces a deadline to pass a stopgap budget for the rest of the federal fiscal year, scientists in research hubs like St. Louis are paying close attention.

The government is operating on a stop-gap spending bill passed last December, which expires Friday. Lawmakers have proposed a continuing resolution to give themselves another week to deliberate. Later this summer, they will consider President Donald Trump's budget for 2018, which proposes steep cuts to domestic spending. Those include a $6 billion hit to the National Institutes of Health, which funds medical research throughout the country.

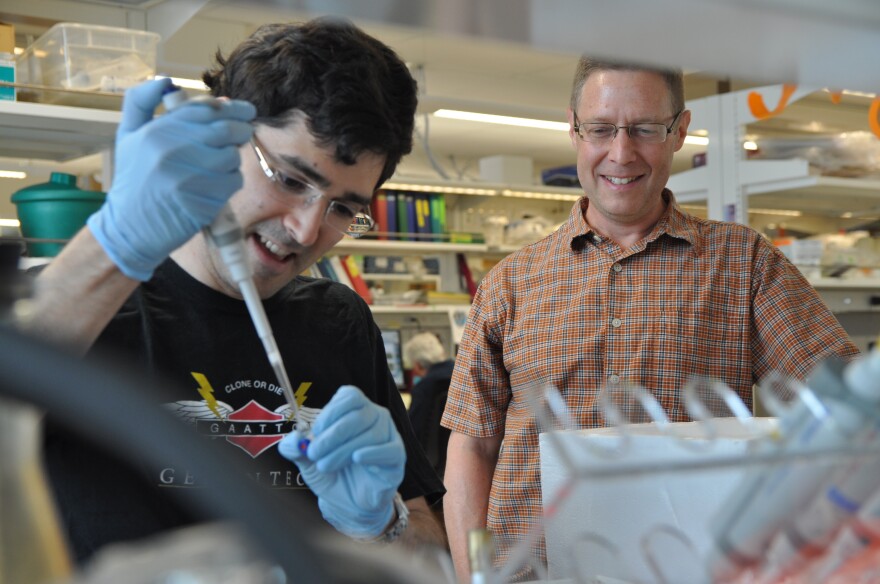

St. Louis Public Radio’s Durrie Bouscaren spoke with Mike White, a geneticist who studies hereditary eye diseases at the Washington University School of Medicine. Last month, White wrote an article for Pacific Standard magazine about what these cuts would mean to a new generation of scientists.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Bouscaren: You wrote in your article that cuts to research funding would hit younger scientists particularly hard. What does that look like for you?

White: I have a grant proposal. It’s really my first grant proposal where I’m the lead scientist on that proposal. I submitted it last February, in fact. It went through the review process; it got a pretty decent score. If this had been 2015, 2016, I would probably already have the money. But, as it is now, it’s in limbo, and I don’t know if I’m going to get the money. If part of this budget compromise, if they cut money from the NIH, it means I may not get this grant. And the clock is ticking for me. I have to get a grant within a certain amount of time if I’m going to keep my job.

Bouscaren: Trump’s budget calls for a $6 billion cut to the NIH. But NIH's total budget has already been constricted in the past decade or so, hovering around $30 billion a year. How has that shaped the field?

White: As that budget goes down, it gets harder and harder for people to get grant proposals. It means every time you submit an application, your chances of getting that grant awarded are a lot smaller. And so what that means is people are less willing to take risks, scientific risks. People are less willing to try out their bold ideas that may or may not work, but they’re good ideas and they should be tried.

Bouscaren: The alternative, of course, is privately funded medical research. In your opinion, is there a case for that?

White: There is a great case for privately funded research. Mark Zuckerburg (founder of Facebook) has established a new source of private funding for research. It’s very generous; it’s very helpful. It contributes to important programs but it’s actually a fairly small drop in the bucket compared to the NIH budget. There’s definitely a concern that private sources of money for research can skew research in the direction that the people who give that money want; [to study] the diseases that affect people who are wealthy philanthropists. Whereas at the NIH, they can take a more global perspective. They can ask what’s affecting people in the United States broadly, or even in the world more broadly, and fund research that focuses on areas that sorely need money but might not attract the private funding you might hope for.

Bouscaren: What’s the bottom line when it comes to research funding? What’s at stake?

White: In the end, it means there are diseases that won’t be cured. There are inventions that won’t be made; new drugs won’t be discovered. I think one important thing that gets lost in these budget battles that seem to come up every year now, is that science is a long-term endeavor. And if we really want science to be successful in this country, we need to engage in long-term thinking. And if every year scientists are worried about budget cuts, about whether or not they’re gonna get their grant, we lose that long-term perspective. And in the end, science is going to be harmed by it, and we’ll all be harmed by it.

Follow Durrie on Twitter: @durrieB.

Follow Mike White: @genologos.

This story has been updated to clarify the timeline for the federal budget.