In what looks like a typical doctor’s office, Gary Newcomer, 26, waited to have his blood drawn for the last time as a participant in a trial for a Zika virus vaccine.

Newcomer has visited Saint Louis University’s Center for Vaccine Development 16 times since November 2016. But a cut in federal funding is bringing a halt to the trial before a vaccine can be developed.

On a recent visit to the center, nurse Tom Pacatte led him back into an exam room and asked Newcomer a series of questions.

“Have you been through a Zika endemic area? Any numbness, tingling in any part of your body? Difficulty walking, climbing stairs, difficulty with balance?” Pacatte asked. “Aren’t you glad this is your last visit, you don’t have to answer these questions anymore?”

Newcomer shook his head to Pacatte’s questions and laughed at the last. Then, Pacatte prepared to draw blood from Newcomer’s right arm, a routine part of the visits.

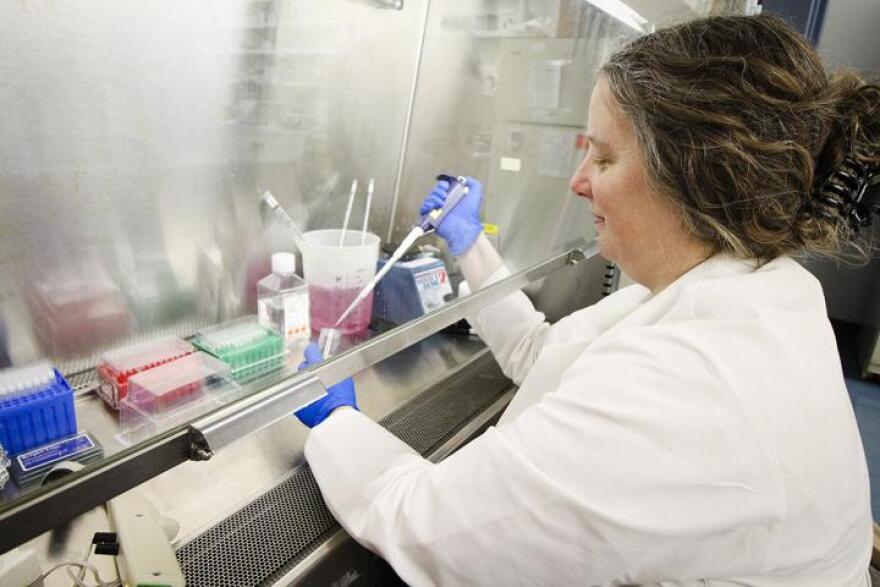

Twice, participants received a booster shot that was either the vaccine, which contains a deactivated Zika virus, or a placebo. Researchers then study the blood samples to see if the vaccine is eliciting an ideal immune response. Newcomer won’t know if he received the vaccine until the end of the year when SLU’s finished with the first phase of the trial.

But for the time being, there are no plans for the vaccine to proceed into the second phase, in which scientists would conduct more safety testing. The trial’s sponsor, pharmaceutical company Sanofi, withdrew funding in the fall after the National Institutes of Health cut its financial assistance. Public interest in a Zika vaccine has also waned, as the number of cases have fallen in the Americas over the last two years.

Zika, which is transmitted by mosquitoes and can cause severe birth defects in humans, has been particularly devastating in several South American countries and the Caribbean.

“How the vaccine is going to go forward is not known at this time,” said Sarah George, an infectious disease researcher at SLU.

George is leading the trial at SLU and is coordinating with researchers conducting another trial in Puerto Rico. The vaccine was developed by the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Last month, George and other researchers published preliminary findings in The Lancet, showing that the vaccine had produced protective immune responses in human subjects.

As someone who’s worked in vaccine development for many years, George has become accustomed to seeing research get repeatedly shelved.

“This is something people wrestle with in the vaccine development field,” George said. “The public interest moves on and with it, the funding tends to decline. And yet, we know Zika will be back.”

With mosquito-borne viruses, a resurgence in infections is inevitable.

“You get a new virus introduced, it goes through the population,” she said. “It infects those who are vulnerable and then the case rate declines. In another 10 or 15 years, you have another group of people who are still vulnerable to Zika and the virus is still out there and so will the mosquitos.”

That’s more reason to move forward with a vaccine. But health policy has always taken a reactive approach, said Celina Valencia, a postdoctoral researcher in public health at the University of Arizona.

“It’s to our detriment that instead of getting out in front of the ball, we’re waiting for that ball to move again,” Valencia said. “How many infections is it going to take for us to pick up again on the vaccine trials?”

The more research that’s conducted on the virus, the more doctors understand how it interacts with the human body. For example, it’s thanks to studies that occurred early on in the epidemic that scientists learned that the virus can be sexually transmitted.

“If we created a vaccine, we would become more intimate with those viruses,” Valencia said. “It’s these little threads of knowledge that are really helpful for public health intervention.”

Follow Eli on Twitter: @StoriesByEli