On a hot morning in Cape Girardeau, two men pulled up nets from a lake in hopes of catching alligator gar, one of the largest and most feared fish species in North America.

They’re scientists with the Missouri Department of Conservation, which has spent 12 years trying to restore the alligator gar’s dwindling population in the state. Its numbers in Missouri have fallen partly because the state doesn’t have strong regulations to prevent overfishing of the species.

Man-made structures like levees and dams have also separated the Mississippi River from the floodplain. They block the alligator gar from reaching critical habitat, said Solomon David, an aquatic ecologist at Nicholls State University in Louisiana.

“We've really altered sort of the natural patterns of how some of these large river systems work and therefore prevent some of these species from accessing spawning grounds that they need in order to reproduce,” David said.

Alligator gar benefit from high waters

Alligator gar, like alligators, have long bodies, large snouts and many teeth. The largest caught in Missouri was 6.9 feet long and 127 pounds, though fishermen have caught some downstream that were more than 300 pounds.

Its size and appearance have led to menacing depictions of the species, which was featured in an episode of the Discovery Channel’s "River Monsters."

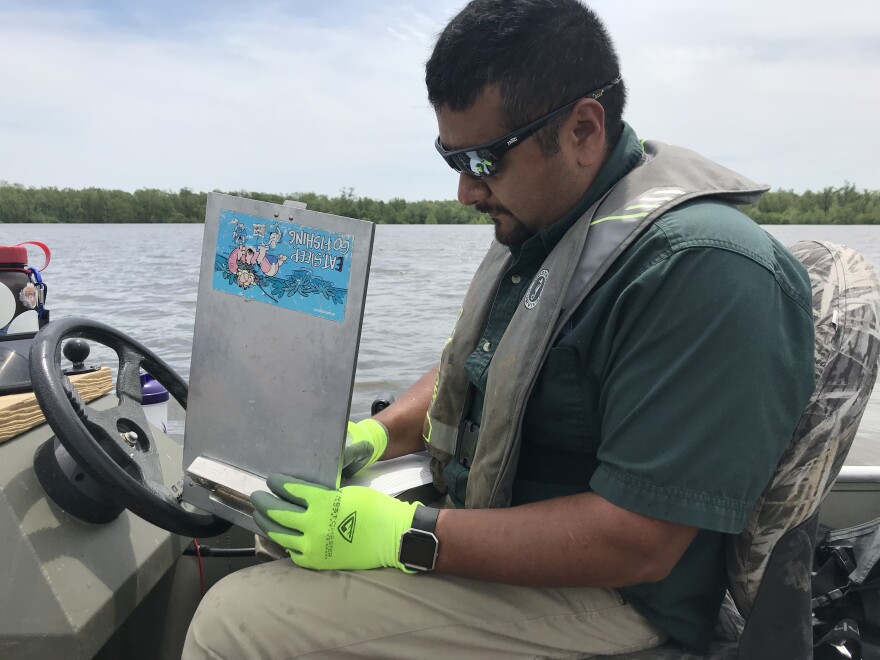

But alligator gar are not very aggressive, said Salvador Mondragon, a fisheries management biologist at the Missouri Department of Conservation.

“A lot of people think that when you get them in the boat, they’re going to try to flop around and bite you. And actually, they just lay there,” Mondragon said. “They let you measure them, do what you need to do, and then you release them.”

Research has shown that alligator gar need waters to be above 70 degrees to spawn, which occurs in May and June. A flood needs to occur so that the fish will seek out swamps and areas along the floodplain that have aquatic plants that are ideal for laying eggs. Finally, the water needs to stay high for several days so that the eggs can develop into fry, or young fish.

But inconsistent flood patterns in recent years, levee building and river dredging have affected the alligator gar’s ability to access the floodplain, Mondragon said.

“Research has shown that with levees, it restricts floodplain habitat,” Mondragon said. “[Scientists] have found out that gar utilize floodplains as much as the river system.”

Helping the alligator gar means helping the environment

The Missouri Department of Conservation does not have an estimate on how many alligator gar exist in Missouri because they’re difficult to catch. However, sampling efforts in Missouri and Illinois have turned up fewer alligator gar than in southern states, like Texas and Louisiana, which have more stable populations.

Missouri conservation officials have stocked the species in locations near the Mississippi River eight times since 2007. The alligator gar that Missouri receives come from mature fish that are raised in Louisiana and are brought to Mississippi to spawn. Then the fry, or young fish, are brought to a hatchery in Oklahoma, where they grow up to six inches before being sent to Missouri.

Like any predatory species, alligator gar help bring balance to the ecosystem, said Louisiana researcher Solomon David.

“If you have too many prey fish, they can sometimes overpopulate and then you might end up with disease, you might end up with stunted populations, whereas the predators help maintain that balance,” David said.

Alligator gar can also help the environment by preying on Asian carp and other invasive species, Mondragon said.

“For some states, that’s the main reason they’re stocking alligator gar,” Mondragon said. “It’s in hopes that they’ll bring some balance to the exotics that are in the system.”

Mondragon has attempted twice to petition his department to include alligator gar on its list of endangered species. Fishermen can catch the species in Missouri without reporting it to the state. If it’s listed, then scientists would receive more funding to research alligator gar and better protect the species, Mondragon said.

“With bowfishing becoming such a big sport, they want to see the species back in Missouri,” Mondragon said.

However, the conservation department has largely rejected the measure due to a lack of public support. Some sportsmen also argue that when alligator gar are young and small, they look similar to other fish. But that argument isn’t strong, Mondragon said.

“When you’re duck hunting ... you have to be able to identify the species before you shoot it,” he said. “Why shouldn’t it be the same with alligator gar?”

Are alligator gar coming back?

In recent years, Mondragon said he’s been able to catch more alligator gar in southeast Missouri. He’s catching bigger ones, too.

“In November, it took three of us to get the fish in the boat; it was very difficult,” Mondragon said.

Researchers at the Missouri University of Science & Technology in Rolla are analyzing genetic materials from alligator gar that Mondragon has caught this summer. The work will determine whether the gar that state conservation scientists have been catching are offspring of the stocked fish or another population, said Dave Duvernell, a biologist at Missouri S&T.

“The other possibility is that these fish were always present in these habitats in low numbers and the native population is simply recovering,” Duvernell said.

Follow Eli on Twitter: @StoriesByEli

Send questions and comments about this story to feedback@stlpublicradio.org