When Missouri outlawed abortion two years ago, Nicole was far more worried for her grown children than for herself.

It had been two decades since she last gave birth, when she suffered a serious stroke during labor followed by severe postpartum depression. She was outraged that the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the constitutional right to abortion, but pregnancy was in Nicole’s past.

That changed a couple weeks later, when her IUD failed.

“Are you kidding me?” she recalls thinking, looking around at the life she and her husband had built together in southwest Missouri.

In her 40s and living in a state where virtually every abortion is now banned, Nicole — who asked to only be identified by her middle name for fear of prosecution — was among the first of thousands of Missouri women forced to navigate abortion access in a post-Roe world.

On June 24, 2022, Missouri became the first state in the country to respond to the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health, striking down Roe v. Wade and the constitutional right to an abortion. The Republican-run state quickly enacted its trigger law banning all abortions with limited exceptions in cases of medical emergencies.

In the two years since, countless women like Nicole have faced already tough decisions made more excruciating by having to find discreet ways to manage their own health or travel far from home for care.

Missouri already had some of the strictest abortion regulations in the country, pushing most women seeking access to the procedure out of state. But the end of Roe raised the stakes, leaving women in Missouri — which already has some of the highest maternal mortality rates in the country — fearful that in the most extreme cases, the ban could mean their death.

Last year, approximately 2,860 Missourians traveled to Kansas last year for abortions, and 8,710 traveled to Illinois, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive rights research group that closely tracks abortion data. But they made up only about 10% of the total abortion patients in each state.

After Dobbs, Missourians’ access to care in states like Kansas and Illinois became precarious as abortion bans became more widespread.

“In a matter of months, we started serving patients from Texas and Arkansas and Oklahoma,” Emily Wales, CEO and president of Planned Parenthood Great Plains, said of the time immediately following the Dobbs decision. “Missourians had to really compete for too few appointments.”

The longer wait times at clinics and barriers to traveling for abortions has led Missourians to increasingly consider self-managed abortions.

That includes Nicole, who received an envelope at home marked with international postage containing Mifepristone and Misoprostol after consulting an online doctor she found through Plan C, an abortion-pill provider.

Missourians navigate abortion access after Dobbs

For Nicole, the decision to end her most recent pregnancy was simple. To continue felt unsafe, she said, and she and her husband didn’t want to start over raising a child.

But the conversations that followed were kept strictly between the husband and wife.

With pervasive uncertainty around whether or not women could be prosecuted for self-administering medication abortions in Missouri, the stakes are higher than ever for those trying to end unwanted or medically complicated pregnancies.

It’s why Nicole didn’t tell her pastor at church. She didn’t tell friends or family. Nicole didn’t even tell her gynecologist, fearing she would be reported by someone in their corner of the state where anti-abortion messaging proliferates billboards, bumper stickers and handwritten signs staked into yards.

Ultimately, Nicole couldn’t imagine fleeing her state for the procedure. She wanted to be home.

“I felt really angry that I would have to leave my community,” she said. “It’s not a shameful thing, it’s a procedure. It’s a medical health care procedure.”

In the six months after the Dobbs decision, the number of self-managed medication abortions rose by more than 26,000 across the U.S. according to a study published in JAMA, the American Medical Association’s journal.

While medication abortions are overall very safe, effective and approved by the FDA to end pregnancies up to 10 weeks, there is some risk associated with any medication. Self-managing an abortion alone, without a local medical provider’s guidance, can be nerve-wracking.

In the unlikely situation that Nicole started hemorrhaging, she and her husband mapped out the closest Kansas hospital that would have the level of care they needed.

When the time came, they both took a day off work and snuggled on the couch. Nicole pressed a heating pad to her abdomen to soothe the cramps, which she described as similar to period pains. Then came the relief.

After the abortion, her husband got a vasectomy. She kept the IUD. Despite their precautions, sex is now accompanied by paranoia as Nicole counts down the days to her period each month.

She ordered extra abortion medication in case anyone she knows might need it. And despite the nearly two years since her abortion, Nicole said she still can’t shake the absurdity she felt hunkering down in her home that day.

“I make decisions for myself every day, and I make good decisions,” she said. “The audacity that people think I can’t make the best healthcare decisions for myself — it’s hard for me to put into words how upsetting it is.”

‘I am desperate’

Stories of women desperate to end their pregnancies proliferate the internet.

Reddit is increasingly a gathering place for those seeking answers and assurance. Many of the posts — all anonymous — illustrate how terrified many Missourians are.

In one post from mid-June, a 23-year-old woman from Missouri feared she was pregnant by her abusive boyfriend but didn’t have the money to travel for an abortion.

“I will drink an entire bottle of vodka if I have to idc,” she wrote. Other anonymous users quickly took to the page to offer other solutions.

In a 2023 post, someone inquired about getting an abortion for their pregnant 15-year-old sister in Missouri without parental consent.

“This experience is causing her to have suicidal thoughts, crippling anxiety, and extreme depression,” the user wrote. “All of which she already had before this. I need help. I am desperate. I do not want to lose my baby sister.”

Even for those who work in abortion-rights advocacy, navigating an abortion post-Roe is anxiety-inducing.

Maggie Olivia first got pregnant while living in St. Louis in 2020. She was on birth control at the time.

Because of Missouri’s “targeted regulation of abortion providers” laws, including mandatory pelvic exams for medication abortions and 72-hour waiting period between the initial appointment and a surgical abortion, she was encouraged to go to a Planned Parenthood in Illinois.

It was clinic escorts with Abortion Action Missouri who guided Olivia into her appointment just across the Mississippi River and reassured her ahead of the procedure. She was so moved by their kindness that Olivia went on to volunteer with the group, and now serves as a senior policy manager with the abortion-rights group.

In the months after the Dobbs decision, Olivia, like many in abortion advocacy work, was navigating the ever-changing landscape of abortion access. At the same time, Olivia said she was mistakenly denied her birth control prescription by a pharmacist after switching contraceptive methods.

When a pregnancy test came back positive several weeks later, Olivia’s first call was to her boss, who she said offered immediate support and guidance.

“But even that close proximity to the reality of the crisis doesn’t make being pregnant when you don’t want to be any less horrifying,” she said.

Unlike with her first pregnancy, Olivia decided not to tell her health care providers in Missouri.

But after ending up in the emergency room for unrelated reasons, her pregnancy was noted in her records. Months later, Olivia said she was denied access to an unrelated medication because her medical records said she was pregnant, compounding the fear she already had of being punished in some way for having an abortion, however legal, in Illinois.

“It was very upsetting,” Olivia said. “And I had thought that I had taken steps to be precautious.”

When she had her second abortion at the same Illinois clinic from two years prior, she also had an IUD placed.

“Your access to abortion doesn’t need to be attached to some traumatic, horrifying situation in of itself,” Olivia said. “Being pregnant when you don’t want to be is scary enough, is horrifying enough.”

Higher stakes for providers

When a sonographer approaches Dr. Jennifer Smith, a St. Louis OB-GYN, her heart drops.

“Every time I look at a fetal ultrasound, it takes on new intensity and new anxiety,” she said, concerned that her patient will have a diagnosis they can’t be of help with in Missouri.

Missouri physicians are balancing medically complex pregnant patients with legal restrictions that could land them in prison for up to 15 years if they perform an abortion the state finds was unnecessary, and, therefore, illegal.

No providers have been prosecuted at this point, but the ways something could go wrong keep Smith up at night. So, too, does the future of not only maternal health care, but also motherhood in Missouri.

“Missouri women are afraid to be pregnant in Missouri,” Smith said. “They are so worried that they might die while pregnant, or that they may get pregnant with a baby with anomalies and have no options because they live in Missouri.”

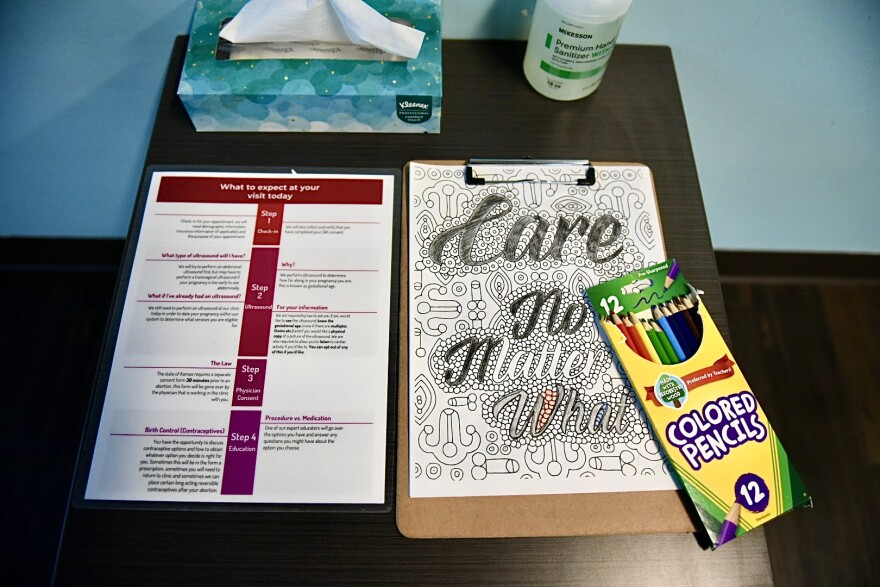

While Smith is often helping women who want to be pregnant, a couple miles across the river in Illinois sits the regional logistics center for Planned Parenthood of the St. Louis Region and Southwest Missouri. There, three patient navigators help those trying to end their pregnancies.

Kenicia Page, the call center manager, said she saw a tremendous increase in callers from the West Palm Beach area, more than 1,100 miles south, when Florida’s ban went into place on May 1.

Right now, she says the clinic receives about 100 calls a day.

They act as pseudo travel planners and financial aid counselors, helping book transportation and finding funding for patients.

Despite the comparative proximity, transportation can still be a headache for some Missourians, particularly those in rural parts of the state without access to public transportation like Greyhound buses or Amtrak, Page said. Sometimes, when the patient doesn’t have a vehicle, nor access to public transportation or car rental services, their next best option is to rent a U-Haul to drive to their appointment.

But more often, Page said, she hears from Missourians trying to find and afford child care, or from minors who need a legal guardian to give consent for financial assistance. Some days Page still finds herself breaking the news to Missouri callers that abortion is illegal within their state borders, and that they will likely have to take a multi-day trip to Illinois to get care.

Page recently spoke with a woman who was homeless and living in a hotel with her children. She had no child-care options, nor a place to stay after the procedure. Page’s team helped connect the woman to funders who assisted with the day care fees and made sure she had a safe place to recover overnight in Illinois.

Their work is done when they get the final call or text from a patient saying they’ve returned home safely.

“It gives you that extra energy or extra push, determination, to continue to do what you do,” Page said. “Because it is definitely making a difference.”

Alison Dreith’s hotline through Midwest Access Coalition, an abortion fund based in Illinois, used to serve a majority of Missouri clients. As of mid-June, only 26 of the total 1,052 callers this year were from Missouri. Now most of her calls come from Texas, Indiana and Tennessee as patients from red states crowd clinics in Illinois and Kansas.

“Every time a new state goes,” Dreith said, “it has the ripple effect that reaches the Midwest.”

The need for child care is a refrain for patients, particularly lower-income Missourians, traveling to Kansas overnight for the procedure, said Wales, with Planned Parenthood Great Plains.

The short drive from Kansas City to Wyandotte or Johnson counties in Kansas has expanded from a fissure to a canyon for some patients. Those requesting medication abortions are usually seen within a week, but patients needing in-clinic abortions can wait two or three weeks to be seen, Wales said.

“We have to explain that we may be close to you, but we are seeing patients from around the region,” she said. “It doesn’t make it easier, necessarily, to get an appointment.”

Wales said many patients are also coming to them later in gestational age, and increasingly with fetal abnormalities. This is a theme across the country, as patients work to find an appointment, save up money and arrange time off work.

Because of the increase in demand, Planned Parenthood Great Plains will soon start seeing patients for abortions in Pittsburg, making it the fourth Kansas clinic to offer the procedure. She hopes that will cut down on drive times for Missourians in regions including Joplin and Springfield.

Julie Burkhart, co-owner of Hope Clinic, an abortion provider in Granite City, Illinois, has seen the number of Missourians served at her clinic more than triple since 2019. But even so, the percentage of total patients from Missouri has gone from more than 60% to less than half as patients from 28 states made their way to her clinic near the Mississippi River last year.

Wait times hover between one and two weeks. In May, the clinic saw 732 abortion patients; 45 were from Missouri.

Funding needs have skyrocketed since Roe fell, and she’s seen the number of Missouri patients seeking abortions in their second trimester increase to 17% this year. Before Roe, it was closer to 8% for all patients.

“With Roe falling, people who don’t have to think about abortion access every day don’t quite know where to look, who to call, who to talk to,” Burkhart said. “It’s put people in more desperate situations.”

This story was originally published by the Missouri Independent, part of the States Newsroom.

Send questions and comments about this story to feedback@stlpublicradio.org.