If you ask somebody to describe what happened in Ferguson, they might tell you about the tear gas, the protests or the chaos.

As a reporter covering the aftermath of Michael Brown’s death, I remember all of those things. But I can still visualize Derrick Robinson.

Robinson is a bishop who spent a lot of hours on the protest line in Ferguson. In the sweltering August heat, Robinson declared that Brown’s death prompted a closer examination into St. Louis’ soul.

“And this is something that has brewed on the fire for so long,” Robinson said across the street from the Ferguson Fire Station. “And now is the opportunity for them to speak and to speak now.”

Robinson’s utterance turned out to be prophetic: Brown’s death showcased a painful divide between law enforcement and St. Louis’ African-American community. Person after person I interviewed told me stories about how they were denigrated, disrespected and detached from law enforcement.

These types of sentiments spurred demands for concrete public policy change, including a big overhaul on how police officers are trained and how they do their jobs. Many of these suggestions were placed into the final report of the Ferguson Commission, an entity created to study the public policy road ahead after Brown’s death.

But despite high expectations, the Missouri General Assembly declined to pass an array of proposals in the session that followed Brown’s death.

Check out our timeline that reviews the events in Ferguson and the legislative efforts that followed:

Bills to expand the use of body cameras stalled. Efforts to bring in independent prosecutors for police involved killings ran into bipartisan opposition. And measures that would have mandated sensitivity training or strengthened racial profiling laws didn’t make it past the finish line.

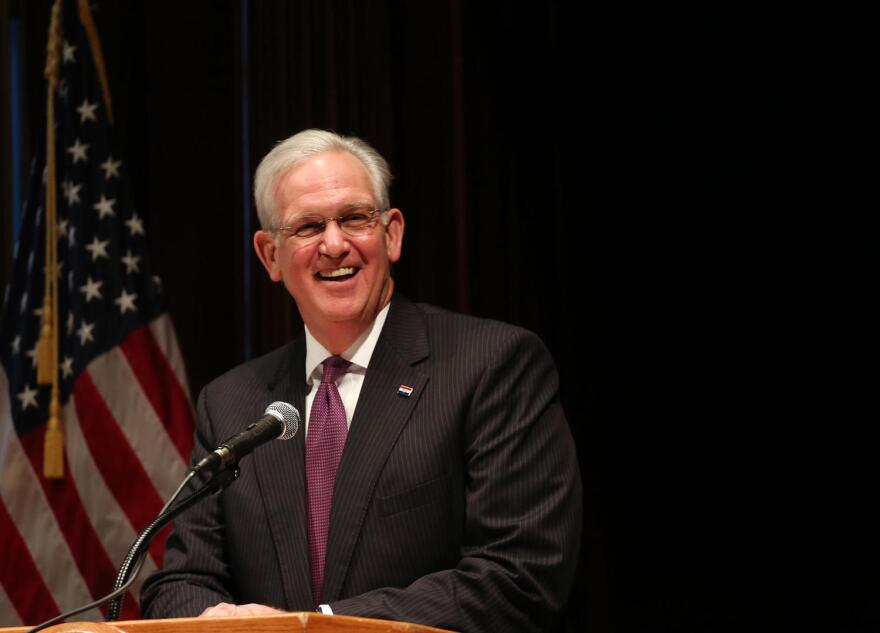

This session was slightly more fruitful, although not by much. A bill that restricts the release of body camera footage made it to Gov. Jay Nixon’s desk, but an effort to mandate their use in some bigger cities did not. And after struggling last year, the legislature effectively repealed an unconstitutional statute governing how police can use deadly force.

House Minority Jake Hummel, D-St. Louis, said this type of output is embarrassing, especially since other states like Colorado, Texas, Illinois, Maryland and South Carolina enacted new laws that were inspired by protester demands.

Other Democrats are even harsher in their criticism.

“It says that they’re not willing to act on African-American issues,” said state Rep. Michael Butler, D-St. Louis, last year. “Let’s be honest. The Ferguson issue really is a black issue. It’s a racial issue. It says that our legislature and Republican leadership does not want to act for black Missourians. When folks bring up race and bring up some glaring issues when it comes to just cultural differences – even if you use the word cultural differences – Republicans have been known to say ‘we want to keep that out of it. We want to keep that out of it.’

“It’s not just legislators. Folks in Missouri are afraid to have the race conversation – even in the St. Louis area,” he added. “We’re afraid to talk about race. And it won’t go away just by doing nothing. It won’t go away by not talking about it.”

Republican leaders, including House Speaker Todd Richardson, R-Poplar Bluff, see things differently. They said it doesn’t make much sense to treat what happened in Ferguson as just about law enforcement.

“As a society and as a culture as a whole, we’ve had difficulty dealing with race issues and talking about race issues,” Richardson said. “And frankly, they’re hard conversations to have. But I think the implication that the legislature didn’t pass a certain subset of bills because of race or some sort of underlying racism is flatly wrong. And despite the fact that I like Rep. Butler very much and we have a good relationship, I think his characterization is way off base.

“The reality is there are things we can do in the law enforcement space that make sense to do,” he added. “No question about it. But if we allow that to dominate the conversation, we’re missing the broader economic and educational issues that exist. Not just in Ferguson, but places across the state.”

“We’re afraid to talk about race. And it won’t go away just by doing nothing. It won’t go away by not talking about it.”Missouri state Rep. Michael Butler, D-St. Louis

Returning empty handed?

Now, it wouldn’t be fair to say that lawmakers did nothing to respond to Brown’s death. In 2015, lawmakers passed an overhaul of municipal governance that pretty much everyone agrees is significant.

Last year’s bill -- widely known as Senate Bill 5 -- restricts the amount of traffic revenue cities can incorporate into their budgets.

And legislation that passed this year takes aim at non-traffic fine revenue, like housing code violations.

Sen. Eric Schmitt, R-Glendale, said these bills got to the root problem that protesters were talking about: A disconnect between government and its people.

“What I constantly heard was there had been a breakdown in trust between people and in their government and people in their courts,” Schmitt said last week. “The common theme here was that this has to be about restoring trust between people and their government. And what I’m very proud of is that law enforcement has been supportive of this too.”

But not everyone had a sanguine opinion about Schmitt’s bill.

A group of primarily African-American mayors sued to strike down a traffic fine cap for St. Louis County – and were initially successful. Other critics of the new law expressed fear it would cause African-American cities to go bankrupt and dissolve – while letting wealthier cities that still take in a lot of fine revenue off the hook.

“It was something that was going to impact communities that did not have ‘a Ferguson situation going down,’” said state Rep. Clem Smith, D-Velda Village Hills. “There are some reforms in the bill that I actually do like. But there should be equal treatment for everyone across the board. But this is a poor excuse. If one would want to use this as an excuse for something we did in Ferguson, it is not.”

Change of heart?

While the Missouri Supreme Court will likely make the final call on the municipal court overhaul, the future for Ferguson-related legislation is not that bright.

For one thing, many candidates running to replace Nixon have a dim view of the public policy push. Many go out of their way to showcase solidarity with law enforcement, while downplaying the Ferguson Commission’s report and proposals emanating from the legislature.

That may mean backers of significant changes may have to go outside the legislature to achieve progress. For instance: While bills mandating certain types of training have gone nowhere, the state’s POST Commission has established new guidelines for how police officers are prepared for the job.

And for his part, Gov. Jay Nixon said during his end-of-session news conference that policy change after Ferguson is not “just changing the law.”

“It’s changing the attitudes and getting people in a situation where this is less confrontational and more progress,” Nixon said. “And I think, quite frankly, we’re making serious progress there. The schools in the area are getting better on a lot of fronts. And I wouldn’t minimize this municipal courts stuff.

“And I certainly deeply know that there have been significant, real attitude shifts in a number of communities across our state,” he added. “I can tell you that without a doubt.”

And a new group called Forward Through Ferguson is trying to get other groups and individuals to buy into the commission’s report. (Although it should be noted law enforcement-related changes would require buy in from politicians.)

Forward Through Ferguson’s Nicole Hudson says St. Louis doesn’t have to wait around for lawmakers to do something. They can make changes on their own. And part of that self-starting strategy includes paying more attention to what the legislature is doing.

“I would encourage anyone who feels as though nothing’s going to happen and the report is on a shelf, my friends and family and the friends and family of other people who are close to working on this that there is plenty of work going on,” Hudson said. “Because we are constantly being pulled in multiple directions at all hours from people in this region who are doing this work and are serious about doing it. So lest somebody tell you that the report is dusting on a shelf, it is definitely not.”