The St. Louis Reparations Commission released its final report Tuesday outlining the deep history of chattel slavery and systemic discrimination in St. Louis and how its continued impact on Black residents has created disparities in housing, education, health care, policing and employment. The commission recommends city officials start repairing the harm caused by racial injustices to Black families that have moved outside the city because of past racism and can prove past or present residency, plus to those who can trace their ancestry to enslaved people in St. Louis.

The eight-member volunteer commission held 27 public meetings from April 2023 through September 2024 in which local experts and scholars shared information on various topics including redlining, environmental harms, health disparities, policing and demolished Black communities in St. Louis. Black residents were allowed to provide testimonies of lived racist experiences and comment on how they would like the city to atone for years of injustice.

From those testimonies, members gathered nearly 40 themes including the destruction of public housing, vacancy issues, financial literacy, medical racism, access to free mental health, disparities in lending mortgage loans, zero-interest loans, cash payments and police violence. They grouped these issues into five core areas to shape the report’s historical analysis of racial discrimination and to provide a framework for racial justice.

The commission based the report on the reparations framework of the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America. It defines reparations as a process of healing, repairing and restoring people who were injured because of their group identity and violations of their fundamental human rights by the government or corporations.

“We believe this report marks the beginning of a new chapter for St. Louis – one rooted in equity, accountability and a shared commitment to healing,” said commission Chair Kayla Reed and Vice Chair Will Ross in the report.

Recommendations

Nearly all of the 109 Black residents who testified demanded that the city pay them in cash ranging from $5,000 a month to millions of dollars to pass down to other generations. While trying to determine the scale of payments, the commission decided that the city must create a permanent reparations committee with economic experts to calculate the true value of restitution and monitor the city’s progress on the recommendations.

The report does not provide a specific amount of compensation that Black residents should receive from the city for enduring racial injustice. It just recommends distributing general cash payouts to people who can trace their ancestry to enslaved people and Black residents who have been impacted by systemic racism in St. Louis. With the implementation of the permanent committee, the commission demands the city make transparent and equitable systems to determine eligibility.

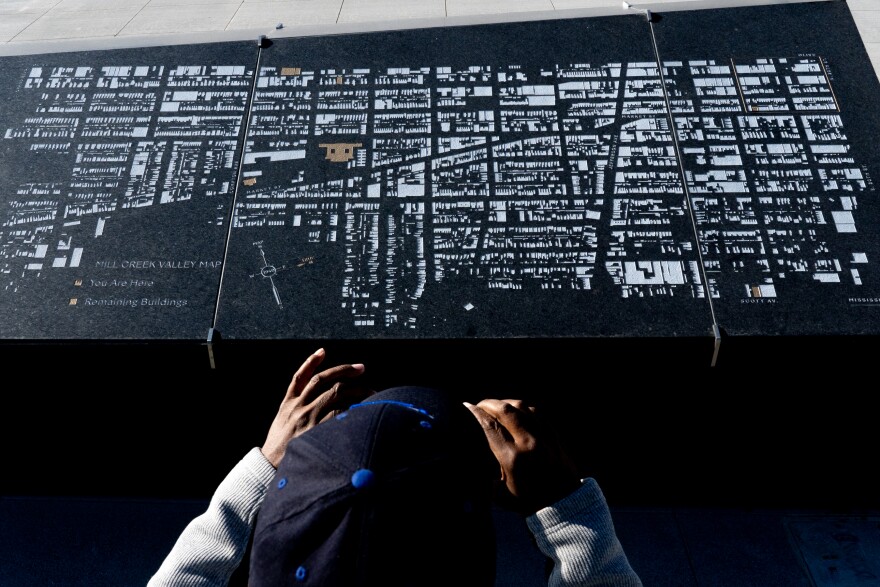

However, the commission does recommend the city provide up to $25,000 to Black former residents or direct descendants of people who lived in Mill Creek Valley, the Pruitt-Igoe public housing project and McRee Town. The targeted payments would compensate families for the city’s involvement in displacing thousands of Black residents from their homes in areas that were later destroyed.

The report does not include possible funding sources for the cash payouts; however, during the last commission meeting, members stated city officials could use money from the St. Louis Rams settlement, unspent ARPA funds, marijuana tax proceeds or general city revenue.

For the core areas, each of the recommendations is categorized into two groups. The restitution recommendations are to address the injustices that affect those directly harmed and to provide redress and compensation to increase opportunities for those affected by systemic inequities. The policy recommendations aim to prevent the repetition of such racist harms in the future through policy reforms.

Those recommendations spanned several categories:

Housing and land ownership

- Establish a fund to provide housing grants to descendants of enslaved people and residents of historically redlined neighborhoods.

- Launch programs for homeownership financial assistance, home repair and property tax relief in historically disadvantaged communities.

- Allocate land for affordable housing developments specifically for Black people impacted by discriminatory practices.

- Offer home repair and property relief grants to Black homeowners in historically underserved communities.

Neighborhood and built environment

- Address pollution and health hazards in Black communities.

- Increase access to public parks and recreation spaces in Black areas.

- Establish a fully funded North City Development Plan.

- Revitalize underfunded Black neighborhoods due to systemic racism and segregation.

Education

- Create scholarships and grants for descendants of enslaved people.

- Provide funding for after-school tutoring, mentoring and technology access in predominantly Black schools.

- Support the development of a Black history curriculum in public schools.

- Increase public school teacher salaries.

- Establish a free WIFI program in St. Louis.

Public health

- Continue funding the St. Louis Health Department, so it will not have to depend on federal grants to function.

- Increase funding to community health centers in Black neighborhoods, so health leaders can create spaces to address intergenerational trauma and stress related to racism.

- Expand access to free or low-cost health care services for low-income Black families.

- Create a community health fund to address racial disparities in health care access and outcomes for Black residents.

Economic justice and wealth creation

- Provide direct cash payments or tax relief for descendants of enslaved St. Louisans and Black residents.

- Provide low-interest loans, business grants and technical support programs to Black entrepreneurs.

- Launch job training and entrepreneurship programs.

Criminal justice and policing

- Establish a reparations fund for victims of police violence, starting with a minimum of $25,000 per documented incident.

- Implement restorative justice programs and mental health crisis response teams by reallocating some of the St. Louis Municipal Police Department’s budget.

- Increase civilian oversight and accountability in the police department, particularly for misconduct cases against Black residents.

State violence and legal reform

- Advocate for legal reforms that reduce mass incarceration.

- Expunge criminal records of nonviolent offenses related to systemic racial injustice.

- Acknowledge the long history of police brutality and the criminalization of Black people.

Members also recommend a public apology to acknowledge the role the city played in slavery and the harmful racist policies that persist today and have caused generational trauma and a lack of wealth building. The report also calls for the city to adopt a formal history acknowledging the past harms that includes detailed accounts of segregation, economic disenfranchisement and redlining. Members also propose the city fund initiatives for Black cultural preservation and historical landmarks.

Quotes from public testimonies are sprinkled throughout the report to showcase direct harm for each recommendation group.

Racial discrimination is deeply entrenched in the makeup of the city, and the commission’s recommendations only serve as a framework to restoring racial injustices in St. Louis. The commission asks the community to continue fighting for equity because one report will not provide complete redress to families.

Reparations Commission issues

Coming to these recommendations was a challenge for the commission. All the members committed hours to the report while working full-time jobs to help produce it.

At the end of 2023, commission members asked Jones to extend the reparations task force to hear more testimony from Black St. Louisans and to prepare and write the final report. Members also asked Jones multiple times to provide a budget for producing the report, compensate scholars and experts who helped with it, and pay for venues and advertisements to gain more community participation.

Reed said commission members and their institutions paid for some venue bookings and advertising fees. The only funding the commission received was through the Missouri Foundation for Health to produce and distribute the final report.

At some monthly in-person commission meetings, there were large crowds of people in attendance, while others garnered fewer than 20. Commission members said during the January virtual meeting that people were frustrated with how they heard about the events. The commission did not have the means to expand its reach by advertising in newspapers, radio and television or through a rolling social media ad campaign.

St. Louis was not alone with low attendance at reparations task force meetings. Other cities like Detroit and Asheville that are studying reparations have reported a lack of trust in the municipal task force's ability to repay Black Americans for racial harm.

“Black folks don't really trust anything that the government is doing. Many Black people just dismiss it as lip service, it's not going to happen,” reparations advocate Robin Rue Simmons told St. Louis Public Radio last November. “We [Evanston, Illinois] had a respectable turnout for our process, but relative to the subject matter, the opportunity and the harm, we should have had standing room only. We didn't have that, and I haven't been to a city yet that has had that.”

Most St. Louisans found out about the monthly commission meetings through local advocacy organizations’ social media posts or word of mouth. The city also kept a calendar of events on its reparations commission page.

“It takes money to do most things because of capitalism,” Reed said during the February meeting. “So, we felt to produce a report and to ensure that report reaches people to collect the stories of the public that we've been hearing in testimony, to provide that history, and what the Executive Order 75 mandates, we would need resources.”

Commission members including Kim Franks and Ross expressed their frustration at the meeting about not having a budget from the mayor’s office. Some members, including Ross, volunteered to create a proposed budget to present to the mayor’s office to get immediate funding.

Throughout the spring and summer, St. Louis Public Radio asked the mayor’s office in email to provide an update on the commission’s work from Jones and the status of the commission’s request for a budget to produce the final report.

In July, Conner Kerrigan, a mayor's office spokesperson, said no other city board or commission operates under a budget unless it is directly collected through tax dollars.

Recently some cities, including Chicago and Washington, D.C., have approved budgets for their reparations task forces.

Although there was no budget for St. Louis’ reparations task force, Jones created a volunteer reparations fund in spring 2022. The city’s Collector of Revenue office began receiving funds in November 2022. Since then, residents contributed $1,411.52 through property tax bills or quarterly water bills.

Rue Simmons, who helped get the nation’s first reparations program approved, said a volunteer reparations fund is a viable option to supplement a budget line-item commitment, but if cities cannot designate reparations funding or find other revenue sources, then cities “have not given the type of tangible commitment, real actionable commitment that I would hope to see from municipalities.”

After receiving the final report, Jones will review it and see which recommendations are feasible to implement, Kerrigan said.