Sunday, Dec. 11, marks 75 years since the United States declared war on Germany and Italy. That was four days after the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, which killed 2,403 Americans, and three days after the U.S. declared war on the Empire of Japan in retaliation.

The United States had officially entered World War II. With that entry, few realize that the nation would open its borders to house prisoners of war from the Axis powers for the remainder of the war.

From 1942 to 1945, more than 400,000 Axis prisoners were shipped to the United States and detained in camps across the nation. Missouri figured into this equation, housing some 15,000 prisoners of war from Germany and Italy inside state lines.

There were comparatively few Japanese prisoners of war brought to the United States during those years and none were held in Missouri.

In 2010, local author and researcher David Fiedler wrote a book about this very history titled “The Enemy Among Us: POWs in Missouri During World War II.” After years of copious research, gathering first-hand accounts, government files and newspaper clippings, he detailed the life POWs led in the some 30 camps that were spread across the state.

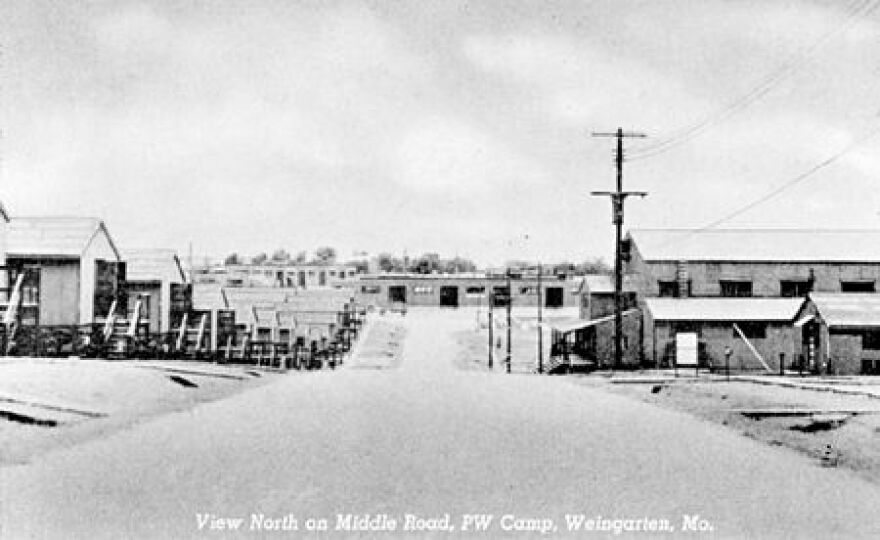

There were originally four main camps in Missouri at Camp Clark, Camp Crowder, Camp Weingarten and Fort Leonard Wood.

“Originally, when the government agreed to bring them here, they were concerned about security,” Fiedler said. “Camps were built on military bases, like Fort Leonard Wood, and within the base there would be a prisoner-of-war compound. The prison camps were identical to housing areas that our own troops occupied.”

Life in the camps

In fact, much of life that prisoners of war led in Missouri during that time was like that of U.S. Army privates serving in those camps: they received the same food and housing, ate meals in the mess halls, were given days off and performed duties ranging from laundry to cooking to working as orderlies in the Officer’s Club.

Prisoners of War were not confined solely to the upkeep of their own numbers: many were put to work in the service of U.S. military operations at the camps themselves. They were even compensated at the same rate of a private, at 10 cents per hour, which could be saved for their release or spent at camp stores.

“The only difference, of course, was large barbed wire fences, search lights and guard dogs,” Fiedler said.

Coexistence

Fielder said that, by and large, the prisoners of war coexisted positively with their American neighbors. Early on, however, that wasn’t always the case. The U.S. government initially did not separate what Fiedler referred to as ‘dyed-in-the-wool Nazis,’ who were committed to the National Socialist movement under Adolf Hitler.

“They weren’t cooperative, they were defiant and intended to cause trouble any way they could,” Fiedler said. “And so, to have that presence in the camps was a difficulty for many reasons including intimidation, threats and physical violence against fellow soldiers whom they considered too compliant in the U.S.”

The U.S. government learned quickly to separate those elements, Fiedler said, and relationships improved.

“No one was happy to be a prisoner of war, but many were glad to bide time to count the days until they got back home,” Fiedler said. “A fairly, easy cooperative relationship grew up over time to the point friendships existed, to be sure.”

Even as conditions worsened for American POWs held in the European theater of World War II and word spread around the United States about Hitler’s efforts to exterminate the Jews, the U.S. government remained firm that prisoners of war should be treated according to the Geneva Conventions. There were some instances where individuals took out personal attacks against the Germans and Italians, but on the whole, Americans accepted that the government was housing prisoners of war in their own backyards.

“I don’t want to imply that people just accepted what the government did, but the ordinary citizen did realize this was a unique time,” Fiedler said. “This was a local story. There was no 24-hour news cycle. People didn’t get in the car and drive 75 miles: it was a locally-focused world. If there was no one around to work the potato fields or the corn was rotting and the local growers association could secure the labor of 100 POWs to pick them and the sheriff felt fine about it, it was not seen as a great concern. This was not seen as a standing thing.”

Entry into the workforce

“The government realized early on that these men were not a threat of escape or destruction or other nefarious deeds,” Fiedler said. “There was such a labor shortage that pretty shortly the government moved these prisoners from the four main military bases to dozens of camps throughout the state. They were much less formal, much less heavily guarded, and there were much more opportunities for social interaction.”

Camps in the St. Louis area included “Gumbo Flats” in the Chesterfield Valley, Jefferson Barracks, riverboats, and an Ordinance Depot in Baden.

Prisoners of war did basic farm work such as harvesting corn or potatoes. In Chesterfield Valley, Fiedler said, there are stories of farmers getting to know the prisoners of war and inviting them in for lunch.

The prisoners were given considerable freedom at these camps. In a memorable encounter, a little girl would leave her bicycle in a certain place every night only to find it moved in the morning. Her family eventually found a prisoner of war using it in the middle of the night to go meet a beau in the moonlight.

The rules weren’t too lax in that regard, actually.

“Romantic relationships remained off limits and strictly forbidden,” Fiedler said. “People got in trouble for it: prisoners expressing affection through love notes were intercepted. American women fell in love with prisoners and a couple of times it turned into aiding escapes, which was considered a traitorous act and a criminal offense.”

Interestingly enough, no marriages were a direct result of the prisoners’ time in Missouri. Indirectly, though?

Fiedler recounted the tale of one Italian gentleman who, after he returned to his home country, wrote to a farmer he worked for in Sikeston remarking on how much he liked working with him. The farmer did not want to respond by letter — but his daughter did, which would eventually result in a marriage.

There were also few wholesale escape attempts made by prisoners of war in Missouri. As Fiedler put it: “Who wanted to rush back into the war? Where are they going to escape to?”

After the war

After the war was over, prisoners of war were not allowed to stay in the United States. For one thing, they were needed to help rebuild European infrastructure. Likewise, hundreds of thousands of American GIs were returning to the states and would need the jobs the prisoners of war would be filling so they were no longer needed for their labor efforts, Fiedler said.

A number of prisoners of war did later return as immigrants and about a dozen of those immigrants settled in St. Louis.

For those that did return to Europe, the United States government hoped they would bring the memory of their equitable experience in the camps here back with them.

“The positive treatment they experienced here, another way we promoted that was a way to say these are people who will go back and reestablish society in Europe and have an opinion on the United States and we want that to be good,” Fiedler said.

Interested in learning more about the experiences of prisoners of war in the United States during World War II? Consider reading Fiedler’s book, which you can find here. You can also listen to this Radiolab piece called “Nazi Summer Camp,” about prisoners of war in Idaho, or read this Smithsonian article about the nationwide POW movement.

St. Louis on the Air brings you the stories of St. Louis and the people who live, work and create in our region. St. Louis on the Air host Don Marsh and producers Mary Edwards, Alex Heuer and Kelly Moffitt give you the information you need to make informed decisions and stay in touch with our diverse and vibrant St. Louis region.

Inform our coverage

This report was prepared with help from our Public Insight Network. Click here to learn more or join our conversation.