Retired Lindenwood University professor Suzanne Sakahara was just six years old when she witnessed two FBI agents enter her house on Vashon Island, Washington, in 1942. They searched the house from top to bottom, looking for hunting rifles and radios for confiscation.

“They even looked in the kitchen at the length of our knives,” Sakahara said on Thursday’s St. Louis on the Air. “If you had too long of a knife, they confiscated it.”

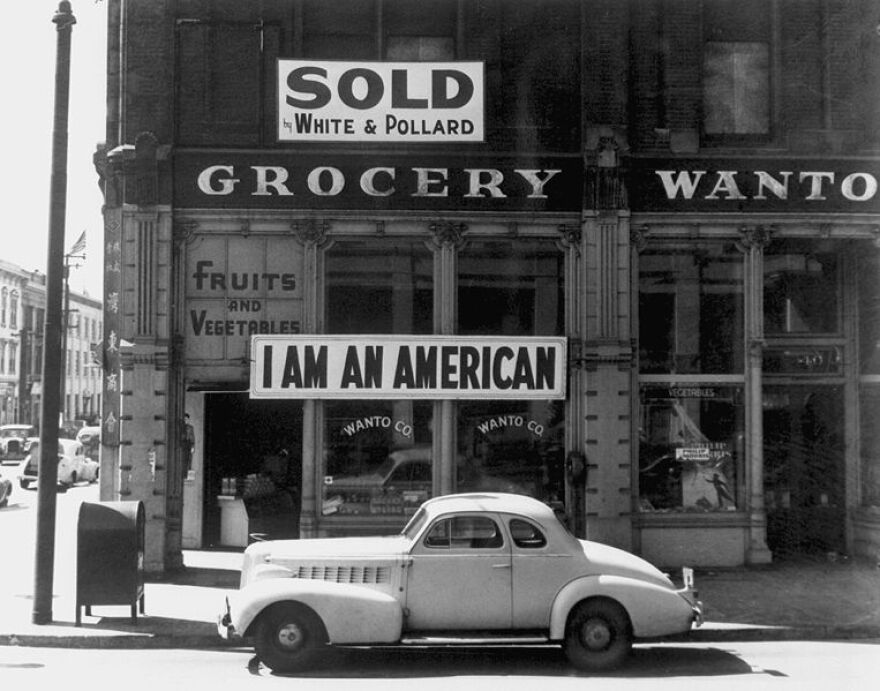

This search was part of the rollback of rights granted to Japanese Americans and people of Japanese ancestry in the United States from 1942 to 1944.

Sunday, February 19 marks 75 years since President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in 1942, which cleared the way for the internment of Japanese Americans from the West Coast during World War II.

By June of 1942, more than 110,000 Japanese Americans were forced to leave behind their belongings, property and livelihoods to be relocated and incarcerated in internment camps across the country. It was not long after the above-mentioned search and seizure that Sakahara and her family would be forced to into an internment camp in California before they were sponsored by a local family to move to and live in St. Louis.

During that time, some Japanese Americans were able to find shelter at inland university programs that would sponsor them away from the internment camps. One such institution was Washington University in St. Louis.

Related: Noted St. Louis architect recounts incredible journey from Japanese American internment to Wash U

In 1944, when the internment orders were lifted, many Japanese Americans who were interned in camps in Arkansas came to St. Louis in search of a new life.

On Thursday’s St. Louis on the Air, we devoted our entire program, hosted by Stephanie Lecci, to looking back at this dark period of American history. We heard from several guests with personal and historical understanding of the years of Japanese American internment, including Suzanne Sakahara.

Rebecca Copeland, a professor of Japanese Language & Literature at Washington University, and Rob Maesaka, a playwright and teacher at Wydown Middle School, also joined the program. Maesaka is in the process of digitally archiving oral histories of St. Louisans who were interned during that time period. He is also working on a play about internment, a follow-up to his 2015 play “White to Gray” about Japanese Americans after Pearl Harbor.

Listen:

Related: 75 years later: St. Louis memories of the Pearl Harbor attacks, the ‘date which will live in infamy’

How it began

Copeland laid the groundwork for the executive order that would change so many lives, saying that prior to World War II, Japanese Americans had been playing a more and more important role in the West Coast economy and that there had a been a history of immigration bans against the Japanese even before Executive Order 9066.

“First generation Japanese who immigrated to the United States were not allowed to own the land they worked, naturalize or keep their savings in banks,” Copeland said. “Their children, however, were entitled to the privileges of American citizens. Their success invited jealousy and animosity from others on the West Coast. When the [Pearl Harbor] attack occurred, it was an opportune moment for many of these voices to express fear of Japanese Americans.”

A tremendous amount of pressure from West Coast politicians, including the governor of the state and mayor of Los Angeles, influenced President Roosevelt to implement an order to incarcerate people of Japanese ancestry. This was met with enthusiasm from General John DeWitt, who was the commanding general of the Western Defense Command, and had extraordinary bias against Japanese Americans.

“The pressure was too much for President Roosevelt to withstand, so he put forward this executive order despite the fact J. Edgar Hoover, director of FBI at the time, said there was no need for it,” Copeland said.

During this time, Sakahara said, there was trepidation and fear in the Japanese American community. She remembers her parents saying to each other that they should “burn anything that’s Japanese: letters, newspapers, records, and any souvenirs,” in case that might hurt them in the eyes of the American government.

Executive Order 9066 did not immediately go into effect; it had to be backed up with legislation that would allow federal courts to enforce the provisions of the order.

“As of March [1942], Public Law 503 gave the War Department the authority to take over the situation,” Maesaka said. “As of April, in major cities, they started to post those famous posters we’ve seen requiring people to go to register.”

When the orders for “evacuation” came, some families were given less than 48 hours to collect their baggage, sell property and head to those relocation centers. Once in those centers, they were sent to 10 different internment camps across the country. Most were in the western United States, but two were located relatively close to St. Louis, in Jerome and Rohwer, Arkansas.

Internment Camp Life

Sakahara said her memories of life in internment camps are shaded through the lens of a 6-year-old. She and her family were first sent to Pinedale Assembly Center, near Fresno.

“If you’ve ever been to Fresno in the summer time, it can be 102 degrees,” Sakahara said. “For the elderly in Washington and Oregon, it was very, very difficult because it was so uncomfortable for them. The quarters, the food, it was very, very different from daily life.”

They were at the assembly center for only a month or two, later being moved to northern California at Tule Lake.

“It was so dusty there — a former lake, all dried up,” Sakahara said. “They had hastily put up barracks for us. The wind blew in the cracks. In the winter, we had these potbellied stoves because it was freezing cold. Each family had a space of 20 feet. If you had a family of four, like my family, you had to share it with a newlywed couple or an elderly couple.”

Sakahara looks back on the time with mixed feelings, differing between her memories as a child and reflections as an adult.

“When you’re a child, you’re playing all the time, you don’t realize the ramifications of such a horrendous thing that’s happened to your family,” Sakahara said. “We tried to carry on with daily life. I think it was like living in a microcosm of living an outside world. … I was in camps from age six to nine. My perspective would be very different than my parents if they were still here. For me, it was fun. It is a terrible thing to say.”

Maesaka said this is a trend in many histories you’ll hear and read from Japanese Americans who were interned.

"When you're a child, you're playing all the time, you don't realize the ramifications of such a horrendous thing that's happened to your family."- Suzanne Sakahara

“There was a great attempt to achieve some kind of normalcy, as odd as that sounds,” Maesaka said. “They set up schools. They had Boy Scouts. They had dances. They tried to recreate as much as they could of American society. The irony did not escape people. The fact that school started with students saying Pledge of Allegiance with the barbed wire fencing is sitting outside the classroom windows…”

Maesaka’s parents lived in Hawaii at the time and he said the approach to people of Japanese ancestry was completely different there.

“Approximately 40 percent of the population of Hawaii was Japanese,” Maesaka said. “… With 40 percent being Japanese, it was difficult to round up that percentage. Even though there was talk of it.”

A few thousand “suspicious figures” were transported to the West Coast for internment, but Maesaka’s father, who was six, and mother, who was one, were allowed to live relatively normally.

“My father was outside playing ball when the attacks on Pearl Harbor happened,” Maesaka said. “He recalls the planes, which were flying low, headed over. My grandmother thought they were filming a movie. It wasn’t until much after that they figured out what was happening. There was a lot of fear at the time. There was uncertainty, people started to bury items or burn items that were Japanese.”

St. Louis connections

When internments began in 1942, university presidents and chancellors throughout the West Coast were terrified about what was happening to their students, Copeland said.

“So, they wrote to the president to get some kind of concession for their students,” Copeland said. “The president handed this off to his wife, Eleanor Roosevelt. She had never been a fan of the camps. She was concerned that Japanese Americans would think this would be permanent, as had happened to Native Americans.”

Working with the Quaker Society and members of the War Relocation Authority, Eleanor Roosevelt was able to create a relocation program of her own: moving Japanese American students on the West Coast to universities on the East Coast and in the Midwest.

Some 600 universities participated. Washington University was one of them. However, even before this relocation became codified, Wash U had already admitted about 15 students from the West Coast and Hawaii. (Read the personal story of one of those students here.)

“I think this is one of the tragedies we see happening now: the loss of brilliant minds,” Copeland said. “These are young people in the prime of their intellectual development. They would have had to put all that intellectual brilliance on hold. In terms of our community, we gained a tremendous asset in students who came to Wash U and stayed. Probably one of the most famous was Gyo Obata, who has been a tremendous member the St. Louis community.”

Sakahara’s family ended up in St. Louis through a different loophole. Toward the end of the war, families would be allowed to leave internment if they would be “sponsored” by an inland family to live with them. Sakahara’s family happened to be sponsored by none other than the commanding officer of Jefferson Barracks. They lived in his three-story mansion.

“No longer did I have to have to be in an elementary school in Montana where children would say ‘Jap, Jap, you’re a sap,’ that sort of thing,” Sakahara said. “Because the children at Jefferson Barracks all went to the Affton School district, you can be sure that word got around that you better not make fun of this little girl because she is living with the commanding officer. We were safe.”

"We're not going back. We're going to make St. Louis our home."- Suzanne Sakahara

Sakahara recalls that an aunt told her mother: “Don’t worry, if you don’t want to go to the West Coast, come to St. Louis, there’s no prejudice against Japanese here,’” Sakahara said.

Her parents never returned to Washington, where a deputy sheriff had seized control of her father’s 70-acre farm and would not return the money for it to him.

“He said: We’re not going back. We’re going to make St. Louis our home,” Sakahara said.

Maesaka said many other Japanese Americans made their home in St. Louis after leaving internment camps in Arkansas (where some 17,000 people were incarcerated) when, at the end of the war, they were given a train ticket and $25 to go anywhere in the country. To do that, you had to go through Union Station in St. Louis. Many people opted not to continue on back to the West Coast and stayed in St. Louis instead.

St. Louis on the Air brings you the stories of St. Louis and the people who live, work and create in our region. St. Louis on the Air host Don Marsh and producers Mary Edwards, Alex Heuer and Kelly Moffitt give you the information you need to make informed decisions and stay in touch with our diverse and vibrant St. Louis region.